You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shoppingThere are many facets to a novel that will early in the work tell me whether or not I will like a book. There are catapulting openers like Cormac McCarthy’s Child of God, whose first chapter unfurls like incantations summoning a demon. Or there are exchanges so instantly captivating, we can’t help but turn the page, like Barbara Browning’s inappropriate intimacy in The Gift.

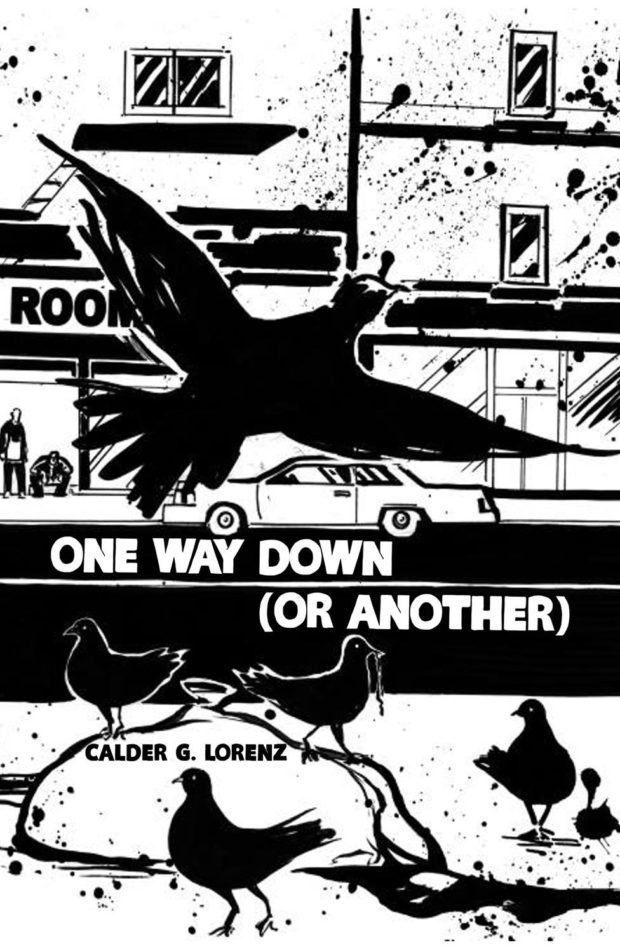

From the first moment in Calder G. Lorenz’s One Way Down (Or Another), we are struck with the author’s undeniable talent for building the most uncomfortable ride:

“And then I thought: Hell, if I stay in San Francisco, I’ll end up like the men who stood in line to build the Golden Gate Bridge, only to fall from the heavens, replaced by the next man in line, just another asshole caught in a net, suspended there, broken back and all, dangling, hung halfway out to hell.”

Henceforth we follow an unnamed narrator on his – intentional or not – journey to take himself down. We meet him in front of a soup kitchen of sorts on his last day of work after completing a program to get sober. Having no prospects, no one to turn to, and no idea what to do next, he seems, already, strung halfway out to hell.

His ex-boss Ray sets him up in a vacant room in his home and gets him a job as a back-up truck driver picking up items people no longer want. He enjoys the job for a time and manages to stay sober – it seems as if things are looking up. There is a resolution (on the narrator’s part) to implode the self, build anew, and test the boundaries of the world, all while doing his best not to fuck everything up. But we know he will, as Lorenz’s unspooling language leads us unblinded toward the cliff.

He stops off at a pizza shop one day on his pickup route because he has some time to kill, and some people just should not have spare time. The narrator wishes, “I’d at least had a paper, or hell, even a pamphlet would be fine, anything to run my eyes over.” He eats a slice, drinks his water, and tries to keep to himself, but the universe – in the form of a bored waitress with two beers in hand – presents an opportunity for error and the narrator takes it.

The spiral to come is both ineluctable and surprising, we know it’s coming, but god if we could only pretend too that yes, he can drive that truck only having had a few beers and sure, he can do just a bump of cocaine. But sadly, we know he can’t. As we edge through part one and read all the inescapable pain to come – the narrator loses his job, is caught drinking by the head of his rehabilitation program, obliterates his sobriety with drugs and drink – the voice of the piece starts to shift. The narrator’s tone changes from that of misguided promise to a kind of resolute hopelessness.

“And as we drove and I mashed down the things I’d done into something I could swallow, I thought about how deserved it was that I found myself on the same highway which only days before had brought me to the ocean, brought me nothing but thought of healing and excitement for something called potential, built and paved with a bit of redemption. And yet, there I was, only to be found falling from yet another precipice. Dangled halfway to that endlessly elusive pit of possibility.”

In this world of uncertainty the narrator has (mostly) created for himself, there is a perpendicular sharpness to the language. As heartbreaking as it can be at times, marching us towards that cliff, there is a unique rhythm and wit to the dialogue:

He said, “I don’t have to explain anything to you. It’s Christmas. It’s my life. And if one day out of an entire year I wanted to dabble, forget, celebrate because I have no one to celebrate with, well, then, I don’t have to explain anything to anyone. This is my home.”

He said, “I hate Christmas.”

He said, “I’m allowed to celebrate. I’ve earned it. It’s been four damn years clean for me. What I do is what I do.”

And I said, “I don’t want to be a burden to anyone.”

And he said, “Well, you damn well are now.”

Resolving not to drag his ex-boss, Ray, down with him, thinking that only one of them would make it out of this last fall together, the narrator leaves San Francisco for his childhood home in Columbus, Ohio, to try and find redemption by salvaging what’s left of his grandfather’s life. Instead, he finds a home nearly gambled away by his step-grandmother, his grandfather careening into full-blown dementia in a nursing home, and some high school acquaintances that want to beat him for wrongdoings past. Even his last attempt to do something good (settle his step-grandmother’s debts) comes out of something terrible (money made through drugs swiped from the nursing home) Thwarted in his redemptive attempts, the narrator returns to San Francisco, “to put an end to all of this failure and failing”.

There are moments that, in a lesser novel, I might find irksome, but in Lorenz’s work I find moving. For instance, some things might’ve felt convenient for the narrator’s arc. People appear and quickly disappear from his life merely to serve something the narrator needed to learn or do. Take for instance, the high-school acquaintances that pummel our narrator in an alleyway for injustices past. The narrator remarks – mid-beating – that it was, “the pain that comes with settling our debts.” These characters appear, the narrator gains an understanding of the moment, and the characters disappear for the remainder of the novel. In a lesser book, this might irritate me, but in Lorenz’s it only enhances the failure and isolation the narrator seems hell-bent on surrounding himself with. The strength of the novel lies in the empathy Lorenz makes us feel towards the narrator. We aren’t reading on for sharp plot turns or otherworldly language, but instead to be caught up in the ebb and flow of the narrator-as-story. Weighty sentences that mimic the narrator’s existential spiral give way to language that is cutting and paratactic and hilariously biting. The balance between the two keeps the reader turning over emotions again and again, creating a novel of hope and hopelessness through switchbacks of sentences.

“A moment is one thing. We’ve all got a shot at that. But you need a lifetime of perfection to ascend to the heavens, and most of us spend our time shattering one thing after the other. We run around with our hammers, trying to fix a world of glass.”

One Way Down (Or Another) is a poignant work of limitations, metamorphoses and, finally, self-destruction. It is a world of escaped realities and broken dreams, companionship and solitude, and, of course, unattainable redemption. It blends the narrator’s life with our own until we somehow, in the end, find ourselves suspended in water, crashing waves around, living out his “own sad little dream” with him.

One Way Down (Or Another) is published by Civil Coping Mechanisms (CCM).

About M.K. Rainey

M.K. Rainey is a southern born writer by way of Arkansas. She currently teaches writing to the youth of America through Community-Word Project and The Writing Institute at Sarah Lawrence. She is the 2017 Winner of the Bechtel Prize at Teachers & Writers Magazine and her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Cider Press Review, 3AM Magazine, The Collagist, The Grief Diaries, and more. She co-hosts the Dead Rabbits Reading Series and lives in Harlem with her dog. Sometimes she writes things the dog likes.