You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

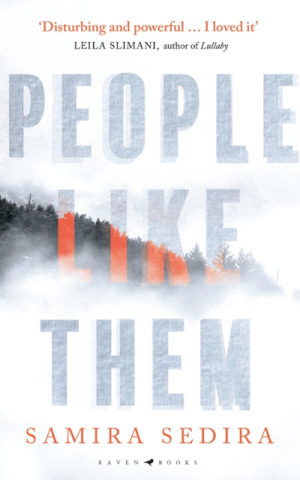

This slim novel is intense and taut. It is based on the horrific murder of a family of five that took place some years ago in the Haute-Savoie region of France. Although the author has fictionalised the event, the crucial details are based on fact and are nothing if not chilling: an apparently happily married man enters his neighbours’ home, kills the three children with a baseball bat, then shoots their parents dead.

Samira Sedira’s fourth novel is the first to have been translated into English, and it certainly deserves the wider distribution. It is close – almost stifling – raising uncomfortable questions about the human condition. What drives people to commit abominable acts? Can they be prevented? These are the questions that Anna Guillot, the murderer’s wife, asks as she recounts, in what is essentially an open letter to the man she loves, the events that led up to that appalling day. She recalls the trial and, long before that, the early years of her marriage to Constant. Anna tries desperately to make sense of her husband’s act, but it is, of course, an impossible task. For who can make sense of the senseless? How can anyone ever truly comprehend why someone they love would commit the unthinkable?

The story is set in Carmac, a remote, isolated village that appears as innocent and idyllic as it ultimately proves to be cruel. When Bakary and Sylvie Langlois first appear, it is late at night, in the afterglow of a raucous summer wedding. Most guests have either gone home, are slumbering drunk around tables of half-eaten food, or are swaying dreamily to the last notes of music that drift across the dance floor. The wedding itself could be the scene of a 19th century painting: Tables are piled high with venison, cured sausage, and stuffed cabbage; pigs rampage wildly amongst the giddy guests, at one point even toppling over the bride who ends up giggling stupidly on the floor. When the Langlois appear, they seem to Anna like “two silhouettes glued together…like some supernatural entity.” Dressed in white, they are ghostly, Bakary’s black face melting “so perfectly into the night” that he appears to have no head. In their otherworldliness, the Langlois are defined from the start as outsiders, Anna’s grim description a gentle reminder of their fate.

This theme of difference is central to the work, a recurring riff: the idea that there exists a separation between “them” and “us.” The people of Carmac inhabit a very insular world, a place seemingly untouched by outside events. When two tourists appear at the local bar asking for directions, they are politely received but gently mocked for their knee-high socks and eccentric habits: “They walk all day in the blistering heat,” one local observes, “and at night they don’t even sleep in a hotel, right? They prefer a tent…” The bafflement is widely shared and helps to explain why the arrival of Bakary and Sylvie, a mixed-race couple with expensive tastes and a garage full of fancy cars, should cause such a stir. As a black man, Bakary reminds the older men of the Senegalese shooters they encountered during the war, there having never been, as Anna points out, any black people in the village before. Ironically enough, it is the very insularity of Carmac that brought the Langlois there in the first place, it representing to them an “authenticity” that could not be found elsewhere.

Yet despite their differences, the Langlois and the Guillots become – at least on the surface – friends, but it is never any easy relationship, marred as it is by jealousy and mutual incomprehension. The Langlois seem just as nonplussed by the locals’ derisive attitudes to newcomers from the city (“They gave up everything to become farmers!”) as the Guillots are by the shelves of books that have all apparently been read. All sorts of currents move below the surface, issues of race and class bubbling steadily up.

Sedira has said that the novel deals not only with racism but also with the invisibility with which people in menial work are often treated. Following a successful acting career, the author worked for a number of years as a cleaning woman and is all too aware of the unconscious prejudice to which service staff are often subjected. Although ostensibly it is envy that fuels Constant’s rage, close reading of the text reveals that self-respect, too, is a driving factor. For although he is fascinated by the flash cars, the big house, and the seemingly easy life that the Langlois live, what tips the balance for Constant is not the material conditions of his neighbours’ lives but the attitudes it allows them to adopt towards him. It is the small slights – a condescending word, a humiliating offer – that cut to the quick so that in the end, it is the petulant glare of a twelve-year-old girl, ‘like she wanted to show me who was boss,’ that sends him over the edge.

The prosecutor, however, has no time for such petty sensibility. He refuses to accept that Constant’s act could have been provoked by ‘a child making a face.’ Instead, he wonders why, having killed five people, Constant would rush out into the cold to wash his hands in the frozen river rather than simply using one of the many bathrooms in his victims’ house? For Sedira, this obscure act serves to demonstrate the insidious, unacknowledged forms of racism that seep into so many daily interactions. Constant weakly explains that he was repulsed by the idea of ‘my blood mixed with their blood,’ a claim his wife brushes off as part a more general phobia that prevented her husband from even attending their own children’s births. Yet as the novel progresses and Constant’s motives begin to take shape, the contours of a racism that is denied and even condoned begin to emerge. We see how it is excused and even enabled by others. When her husband calls Bakary a “fucking ape,” for example, Anna assumes she has misheard. “It should have shocked me,” she says, “but I didn’t react. It’s out of anger I told myself. Anger. Or else, which was more likely, I had heard wrong.” And when it is all over and the trial closed, Anna will acknowledge the implicit responsibility of the bystander, the guilt of family and friends who passively ‘stood back and let it happen.’

The novel is engrossing, swift, and rich in picturesque detail. Not only are village scenes like the wedding or the local carnival beautifully described, so too is the countryside and the seasons by which it is marked. The heat of summer presses down, just as the winter silence is felt as a state of high alert. As such, the novel has very earthy texture that places Constant’s behaviour in a context that is far more elemental than it is simply human. In earlier years, he was a promising athlete, a pole-vaulter who aimed, both literally and metaphorically, for the skies. His ambitions ended, however, when a technical error sent him crashing to the ground, never to vault again. For Sedira, this is the beginning of his demise, the start of the feelings of humiliation and worthlessness that will drive him to his act. Yet the visual image of this man trying to break out, by flying up and over the confines of his small-town world, show something of the desperation and determination by which Constant is driven. He applies all his energy and strength to defeating the gravitational forces that seem, however hard he tries, to be pulling him down, back towards the earth, back to the village and the ice and the rushing river far below. Is he not, then, at one with this place to which he is so inescapably tied? Is he not just as fickle and unpredictable as the local climate, which, according to Anna, can be relied on to “regularly contradict” the inhabitants forecasts? It may well be so.

The author has said that there is “no such thing as monsters, only humans,” and ultimately it is this that People Like Them seeks to show. For in recounting Constant’s tale, it is a litany of human weakness that Sedira lays bare, her demonstration of jealousy, prejudice and pride, a lesson in acceptance and forgiveness that all of us would do well to learn.

People Like Them

By Samira Sedira

Translated by Lara Vergnaud

Raven Books, 178 pages

About Jane Downs

Having grown up in the south of England, Jane went on to study Arabic at university, travelling extensively in the Middle East and North Africa before putting down roots in Paris. Her work includes short stories, poetry, reportage and radio drama. Her audio drama "Battle Cries" was produced by the Wireless Theatre Company in 2013. Her short stories and articles have been published by Pen and Brush and Minerva Rising in the US. In August 2021 she joined the Litro team as Book Review Editor, commissioning reviews of fiction translated into English. Other works can be found on her website:https://scribblatorium.wordpress.com