You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

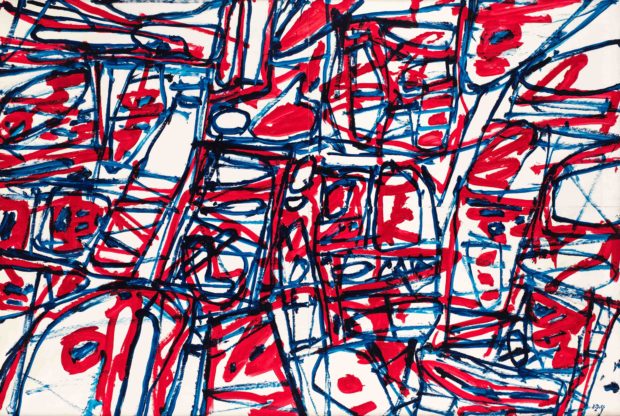

28 December 1983, Courtesy Galerie Jeanne Bucher Jaeger, Paris

ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London, Courtesy Galerie Jeanne Bucher Jaeger, Paris

The comprehensive exhibition at the Barbican is the first major retrospective of Jean Dubuffet’s work in the UK after more than 50 years and covers four decades of the artist’s work. It encompasses all the stages of the artist’s career, from the graffiti-inspired creations of the 1940s – lithographs in black and white depicting a frightened humanity just out of the Second World War – to his portraits from recollection, the mental landscapes, assemblage pieces, sculptures, texturology artworks, and Coucou Bazar’s theatrical props.

Dubuffet employed a wide range of techniques, mainly oil and acrylics on canvas but also ink, vinyl paint, and collage, that he called assemblage, which includes butterfly wings and glass shards. He was inspired by everyday objects and wished to translate them into unexpectedly beautiful artistic products in order to explore virgin fields and break with traditional culture. He was not attracted by the ancient classical world but by the oddities, the “wrinkles” and “troubles” of everyday life. Art was his method of exploring and illuminating the world which, according to him, was made of “many realities.” Trivial things, therefore, become objects of beauty showing what people cannot see but can imagine – that is, the spirit of things.

Dubuffet (1901–1985) started his working career as a wine dealer in the family business. In his forties, he trained at the Académie Julian in Paris and became a professional painter. Despite this traditional beginning, his attitude towards the established concept of artistic beauty and French idea of fine art was rebellious. He meant to liberate art from conventions, renewing it in a constant experimentation that is revealed throughout the different phases of his artistic career, which are well displayed and explained at the Barbican exhibition. Dubuffet can be considered anti-artistic, as some critics claim; but, on the other hand, his work is clearly self-conscious and self-reflexive, showing awareness of what he was doing and what he wished to accomplish. His playfulness and faux-naïve doodles of funny figures are not only disruptive and comical; they are also deliberately mundane, maybe ugly but always original and clever.

His artistic skilfulness is also revealed in the use of materials, from sophisticated lithographs on Auvergne paper in the first works of the 1940s inspired by street graffiti, to the extensive use of oil paints in different intensities, for example in the thick layered texture of his mental landscapes that create a down-to-earth solid vision. He also used acrylics, felt pens, black ink vinyl paint as well as assemblage to make collages of sorts in which he plays with organic and non-organic materials. In his artwork, he celebrates humble objects such as the pavement or soil, depicting them in detailed thin oil paint layers. They reveal his wish to explore, and they serve as symbols of an unpredictable expanding reality that does not mean to be heroic or prophetic. According to Dubuffet, the artist’s goal is to illuminate and discover, rehabilitate what is neglected, explore virgin fields, and create unexpected products. In the video displayed at the end of the exhibition, there is a scene in which Dubuffet collects pebbles and puts them in his pockets; he observes the rocks and the soil, taking inspiration from what is commonly considered worthless or discarded material.

Therefore, his art reveals both the vulnerable side of being human and the visionary view that prompts experimentation and creativity. This complex vision was intended to reform Western art through the belief that new frontiers should be achieved beyond tradition, which he considered boring, repetitive, and predictable. This defiant attitude is particularly evident in his portraits from recollection in which he did not paint the sitter from life but from what he remembered after an attentive observation session that could take hours. They are apparently funny figures in which varnish and plaster were thickly layered and then scraped or cut with a stick or a knife.

July–August 1947, Private Collection

ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London, Courtesy Private

Collection

Another example of this approach are the “Ladies’ Bodies” (1950s, ink on paper and oil painting on boards), which are in opposition to the ideal notion of female beauty present in ancient Greek art and in today’s magazine covers. His female bodies focus on internal fluids, the inner intimate parts that unsettle the viewer and open up to a landscape of flesh. They are sensual and disturbing at the same time.

During his life, Dubuffet also collected what he called Art Brut (raw art) – that is, the artworks of artists in psychiatric care or visionaries. They are outsiders who were considered to be at the margins of the art world. Most of these works are untitled and range from detailed figurative pictures to totally abstract pieces. Dubuffet found these works genuine and inspirational and wished to organise an exhibition dedicated to Art Brut, which, unfortunately, never happened.

In the 1970s, Dubuffet worked on Cocou Bazar, an installation of theatrical props that was exhibited for the first time at the Guggenheim Museum in New York in 1973. It was a display of performative art with music and light but without any narration. Dubuffet explained that the scenes were intentionally “brutally loud with abrupt interruptions of silence.” They are white figures outlined in black and painted in blues and reds reminiscent of marionettes or puppets; they are entertaining and playful, like most of his artwork.

In his final phase, he seems to revisit and mix all his previous approaches, simplifying the techniques and also commenting on his own past works. The interest in graffiti comes back together with the use of ink, acrylics, and collage. His cartoonish figures intersect with doodles, geometrical shapes, and pure abstract pieces in acrylics.

In this retrospective, a wide range of Dubuffet’s artwork is on display, and the exhibition does a fine job of explaining and analysing the different stages of his career and his belief that “there are as many realities as we want there to be.”

Jean Dubuffet: Brutal Beauty

Barbican Art Gallery, London, UK

17 May– 22 August 2021

About Carla Scarano D'Antonio

Carla Scarano D’Antonio lives in Surrey with her family. She has a degree in Foreign Languages and Literature and a degree in Italian Language and Literature from the University of Rome, La Sapienza. She obtained her Degree of Master of Arts in Creative Writing at Lancaster University in 2012. She has published her creative work in various magazines and reviews. Her short collection, Negotiating Caponata, was published in July 2020. She and Keith Lander won the first prize of the Dryden Translation Competition 2016 with translations of Eugenio Montale’s poems. She completed her PhD degree on Margaret Atwood’s work at the University of Reading and graduated in April 2021.

- Web |

- More Posts(3)