You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

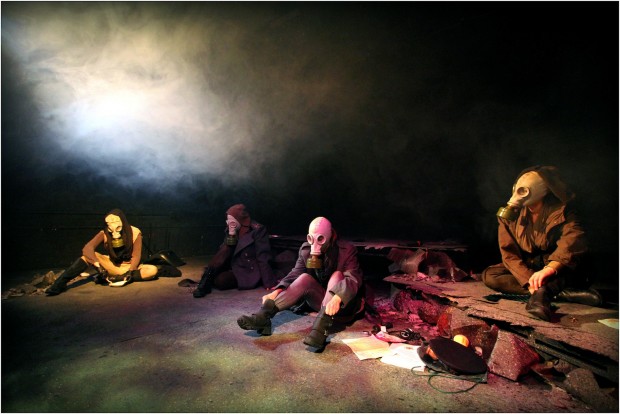

Karl Kraus wrote The Last Days of Mankind, his grim, Goliath satire about the Great War, for a theatre on Mars. “Theatre-goers of this world would not be able to bear it,” and not just for its monstrous length (209 acts over fifteen hours), the quixotic lavishness of its stage directions (a dead forest murmurs, 1200 horses drown, and there’s something about a singing flammenwerfer), Kraus’ palimpsest layering of its scenes and crenellations of obsolete German, weird aphorisms, and allusions to opaque Habsburg history. It’s the unflinching dramatization of “man’s inhumanity to man” that Kraus believed would make it so unbearable. It’s an inhumanity that isn’t contained in no man’s land but exists—originates—in the marbled rooms of Ringstraße palaces, in factories run by profiteering industrialists and stalls by black market opportunists, and especially, for Kraus, in newspaper columns. On his Martian stage, journalists hound a dying man for a headline-worthy quote and racketeers loot the bodies of the dead, telling them how lucky they are to have escaped the slog of profit-making. Here, at the Tristan Bates Theatre, the Last Night epilogue is managed, boldly, with a cast of four, martial footfalls, smoke that evoked both Mars and mustard gas, and a new ringing translation. It’s hallucinatory, hellish and all too human.

Kraus would have a poison pen, then, for our anniversary preoccupations, the dewy-eyed nationalism and stagey grief that has stuffed bookshops, television schedules and school curriculums even fuller with nostalgia and “lest we forget” fables. Catriona Kerridge’s Shoot, I Didn’t Mean That, inspired by and double-billed with the epilogue of The Last Days of Mankind, skewers war and memory—as tedious, puritanical, bureaucratic and unbearably seductive. Her scenes are at once surreal, satirical and ripped from the headlines, as Kraus’s were. They’re also dominated by women—a shift that distinguished her play, director Pamela Schermann said, from the other the responses to their brief, most of which were afflicted with terminal cases of trench foot and maleness.

Kerridge’s triptych of scenes begins mundanely and then detonates, as each woman is tugged into war, protest, racism and bloodshed through boredom, deadly curiosity, and the contentious politics of remembering. A British tourist stumbles across a stall selling Third Reich memorabilia in a Viennese market and, as if possessed, raises her arm in a Nazi salute. It sticks, and that sickening moment of curiosity and defiance when you whisper what you shouldn’t, push the limits of what’s sayable, is frozen, Sieg Heil inscribed into her body. In prison she confronts the gross fascination of the unthinkable further, as she’s adopted by jailhouse neo-Nazis as rallying point and an omen. There’s a hint of Mel Brooks mischief to her paralyzed salute, but the initial shock of her raised arm quickly fades into banality: it goes numb, she learns to sleep on it, lean against walls to disguise it. Alexine Lafaber’s performance was a subtle counterpart to the hyperbole of her salute. Horror and perverse pride creep into her voice when she describes being hailed as a reincarnated Hitler and she tries out mild Holocaust humor with all the shame and glee of a child parroting dirty jokes.

Meanwhile, Sarah, an interpreter, melts down in a glass box amidst a constant stream of political doublespeak about war crimes—“mistakes were made”. She sings, talks back to the politicians she’s translating for, writes “Lies” in lipstick on her glass box. Emily Bairstow plays her with equal parts exhaustion and hilarity. The most harrowing of the scenes escalates, dizzyingly, from the whispering of two schoolgirls during an Armistice Day moment of silence. Their gossipy, wandering, mean-spirited chatter is pitch perfect, and grounds their later unthinkable actions in teenage naivety and thoughtless rebellion. Their evolution from shoving spotted dick into a classmate’s bag to plotting to go Syria and subjecting each other to practice torture seemed almost inexorable—or at least it is when the news frets over teenage girls lured to Syria by ISIS. The climax of their scene was unnerving and desperately sad, as Jocasta King’s Emma melted from mockery to a terrible realization. Shoot, I Didn’t Mean That shows the inhumanity of (wo)man, but also the bluffing, the moments of madness, the rebellions, the “mistakes made” and the seductions that lead us there. Kerridge is inventive and mercilessly funny, and her play stands firmly beside Kraus.