You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

-1-

Except for a confusing and ultimately consequential semester her junior year in college when she abruptly withdrew from her accounting and finance classes and enrolled in Fundamentals of Classical Music, Amalie had always considered herself a conscientious, practical-minded woman whose interest in music extended no further than listening to Top 40 radio during her morning commute to the office. The only reason she enrolled in the class at all was because she had a crush on the cute graduate student teaching it. Said to be a wunderkind who was destined to become a great composer of film scores, the next Erich Wolfgang Korngold or Bernard Herrmann, he sat hunched over a baby grand piano while delivering lectures on Ennio Morricone and his beloved John Williams. What did she know about that sort of thing? To her ears, all orchestral music sounded pretty much the same. Even now, 15 years after graduating with a bachelor’s degree in business administration, she never turned the dial to the classical music station. She just liked the way her teacher wore his dark hair in an impeccably groomed pompadour that fell into his eyes as he pounded away at the keys.

Strange, then, how on a misty autumn evening after work, rather than leave her office at the usual hour and return to the drafty apartment to eat a frozen dinner at the kitchen counter with her family, Amalie walked in a kind of daze along the downtown streets and wandered into a corner bookshop. Usually drawn to cosy mystery stories set in English manor houses or novels about the romantic misadventures of middle-aged divorcées who meet handsome strangers at seaside inns, Amalie made her way to the music section and found herself reaching past Josephine Baker and the Beatles for a heavily annotated volume on Beethoven. In the shop’s café, she ordered a mug of black tea and sat alone at a corner table, her back turned to the rain-streaked windows.

Rather than peruse the table of contents or flip to the illustrations and glossy photographs, she took a moment to study the title page with its elaborate copperplate engraving of a steely-eyed man with a mane of stormed-tossed, white hair. His cravat hung loosely around his upturned collar, and in his right hand, he held a dangerous-looking quill that might have doubled as a poisoned-tipped dart. Unsure of what she was trying to glean from the life of this temperamental, self-involved genius, Amalie turned to the first chapter and read of young Ludwig’s harrowing battle with smallpox; of his unsightly facial scars; of his lack of formal education; of his beloved mother Mary Magdalene who, at the age of forty, died of tuberculosis; of his tyrannical, alcoholic father who beat little Ludwig without mercy and locked him in a roach-infested cellar for the most minor of infractions. The catalogue of horrors ran to hundreds of pages, and Amalie often held a hand to her mouth and shook her head in disbelief.

She checked her watch and decided the time had come to phone Daniel to say she was working late tonight. She had to proofread a few reports, file paperwork, input data. They both knew the overtime would come in handy, but there was no need to state the obvious. After saying goodbye, she decided to bring the book to the sale counter. Last year, Daniel was forced to sell the last of his books as well as his treasured collection of vinyl records, and Amalie decided to surprise him with this small but extravagant gift. Hardcover books with glossy photos and illustrations were pricey.

In the parking garage down the street, she retrieved her overnight bag from the trunk of her car, and then, because the concert didn’t start for another 90 minutes, she walked three blocks to the newly refurbished Bonn Hotel. At the front desk, she requested a deluxe suite, one on a high floor with a view of the lake and city lights. The suite included, to both her shame and delight, a sectional sofa facing an electric fireplace and a spacious kitchenette with a complimentary fruit and cheese plate displayed on the granite countertop. The refrigerator was stocked with chocolates and bottles of sparkling wine, and in the bedroom, there was a writing desk with a fountain pen and stationery. After unpacking her bag, she kicked off her shoes and stretched out in the king-sized bed. She spent another 30 minutes in the company of the great Ludwig, reading of his disdain for the nobility and his bad luck with women, the majority of whom regarded him as revolting in appearance and an inattentive bore. Beethoven, she also learned, inherited his father’s volatile temperament. Once, while trying to compose at his piano, he became so distracted by the loud chatter outside his studio window that he dumped a pot of hot water on a group of men standing on the corner.

Amalie glanced again at her watch. Without marking the page, she put the book on the nightstand and took a seat at the vanity. She touched up her makeup and fixed her hair. There was no time for a proper meal, but she could sneak one quick drink at the hotel bar. In the restaurant off the lobby, she sat alone at the bar and ordered a glass of obscenely priced German wine. Without appreciating its subtle floral notes, she quickly drained her glass and, in honour of the composer, ordered a second. In the mirror behind the bar, she observed a middle-aged couple eating a steak dinner by candlelight. From their prolonged silences, she inferred that they were not happy exactly but had at least learned to tolerate one another.

After paying the alarming tab, Amalie, on an empty stomach, walked light-headed along the avenue toward the flashing neon lights of the arts and entertainment district. At the box office window, she purchased an aisle seat in the upper balcony, just about the worst seat in the house, but only a few tickets remained for tonight’s performance. She reached her seat just as the house lights dimmed and the concertmaster led the orchestra in tuning. After a moment of hushed anticipation, the conductor strode across the stage to thunderous applause. A man of great reputation? From her handbag, Amalie retrieved the programme and, squinting at the tiny print, read about the Austrian-born conductor’s fondness for film music. Tonight’s programme featured works by Johnny Greenwood, Philip Glass, and Jerry Goldsmith. Did the maestro have a purpose for selecting composers whose names began with G? Was it meant to be a kind of theme? Would all of the music be in the key of G? She recalled Daniel telling her that during the Baroque period, G major was regarded as the key of benediction.

To her great disappointment, much of the music had a decidedly experimental quality. There were brief passages of sublime beauty, but mainly the music was ponderous and dull and seemed to go on forever. One piece in particular was relentlessly percussive and bombastic. The screeching violins played a frenzied, atonal passage before the brass and woodwinds blared some kind of demented fanfare. The dissonant score conjured up visions of evil clowns pursuing her down dark alleys. Hoping to catch the eye of someone who was just as confused and disquieted by the music as she was, Amalie glanced to her left and right, but her neighbours seemed enraptured by every note. She didn’t know if she could stand listening for much longer. To the great annoyance of those around her, she rifled through the programme and was disappointed to learn that there was another suite before intermission.

In a wishful attempt to maintain her fading buzz, Amalie slid from her seat immediately after the final crashing note and hurried down to the concert hall’s grand rotunda to order a cocktail. Instead of wine, she chose single malt scotch, but the Glenfiddich tasted so strongly of peat that she could barely finish it. She wandered through the marble rotunda, pretending to appreciate the ornate bronze sculptures of avenging angels and winged serpents. According to a bronze plaque near the grand entranceway, an eccentric recluse with an interest in the shamanic traditions of prescientific peoples had designed the concert hall. Under the right circumstances, he felt the hall could become a sonic vortex capable of transporting attentive listeners to higher realms.

When the applause from the hall died down, people rushed to the rotunda and queued up for a drink. Near the sweeping staircase, Amalie kept a surreptitious eye on the single men lurking in lonely corners. Like her, they seemed vaguely dissatisfied with their situation and stared blankly at the artwork. Even though she was wearing a drab business casual outfit tonight, she caught a few of them glancing her way, including that handsome, young bartender who had poured her scotch. After careful deliberation, she decided there was no cause to panic. She was only 36, still young, and in the soft light had a certain sex appeal. Still, she had little interest in striking up a conversation with a stranger, nor did she wish to return to her seat and listen to more of this bizarre film music. Judging from the programme, the movie studios of old had only financed horror movies and lugubrious character studies about manic depressives.

Her head beginning to ache and her ears still ringing from the relentlessly cacophonous music, Amalie set her glass down on a cocktail table and abruptly exited the concert hall.

-2-

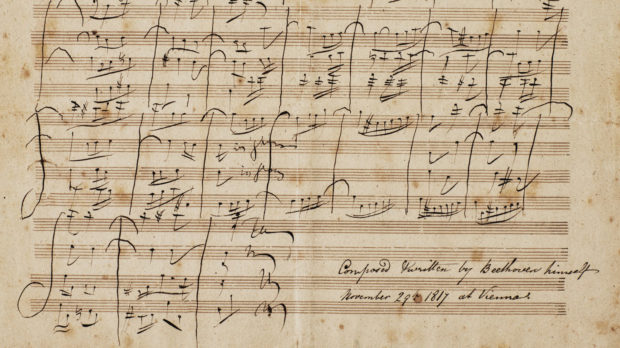

In a moment of spiritual weakness, Beethoven penned a letter addressed to his brothers. Written in a tight slanted script on legal paper, the letter was a long screed in which the young composer finally accepted the cosmic injustice of his humiliating affliction. “Speak louder, shout, for I am deaf!” He blamed incompetent doctors and threatened suicide. Maudlin rubbish, most of it. She certainly didn’t need a Beethoven to tell her that good people sometimes indulged in the fleeting and satisfying pleasures of self-pity. What made the letter so interesting, in Amalie’s estimation, was that instead of mailing it or tossing it into his hearth, Beethoven chose to file it away in a cabinet where it remained for the rest of his life.

Soaking in the enormous freestanding tub, her skin turning pink from the scalding water and lavender soap, Amalie set the book aside and reached for the glass of white wine she had poured. Although she would never appreciate so-called “serious” music, she still believed in the brave example set by Beethoven. She rested her head against the white porcelain, and almost instantly, the knotted muscles in her back began to loosen. For the first time in many months, she did not obsess over the medical bills, the legal fees, the back taxes, the impending bankruptcy. In fact, she thought of nothing at all, not even tonight’s reckless spending. Her mind at peace at long last, she breathed deeply, practically purred, and through half-closed eyes, she saw in the dark depths of a mirror thick with steam a vision of the concert hall.

The ghostly figure of the conductor stood on the dais and led the orchestra not with a simple wave of the baton but with the agile, practically acrobatic, movement of his entire body. He swung his torso left and right, as if evading a prizefighter’s devastating blows, and to the great delight of the audience, the orchestra played a familiar melody. Amalie listened intently and felt tears forming in her eyes. During a short stint in Los Angeles, Daniel had worked on a handful of student films before landing a job composing the theme music and score for a new science fiction television series. Set in the past rather than the future, the short-lived series concerned a powerful priesthood of Native Americans who once inhabited the Chaco Canyon of New Mexico’s Badlands. Using their extraordinary astrological knowledge and monumental architecture, the priests made contact with a group of intergalactic space travellers who taught them the secrets of the cosmos. The series was cancelled mid-season, and Daniel struggled to find more work, but the show’s main theme enjoyed a bit of popularity among aficionados of film and TV music.

Now, as the music reached its resounding finale, the conductor turned away from the score to look over his shoulder, and only then did Amalie recognize her husband. His cheeks were once again full of colour, and his hair had miraculously grown back dark and thick as ever. The vision of health and happiness, he called her name and invited her to join him on stage. She leaped from her seat but couldn’t make her way to the stage. There were too many people dancing in the narrow aisles. All around her, the women hiked up their skirts and kicked their legs like a chorus line of Toulouse-Lautrec showgirls doing the can-can. The handsome bartender asked her to dance and seized her by the arms. He twirled her round and round until, like a bouncing top, she reached the upper balcony. From way up here, Daniel looked like a speck of light at the bottom of a well.

That was when Amalie heard the bathroom door creak slowly open, and she felt a disembodied presence hovering close behind her. Perhaps Daniel’s music, like the ancient priests of the Chaco Canyon, had the power to make contact with higher intelligences. A voice, barely audible above the dripping faucet and not entirely human in its low timbre, advised her on the terrible but necessary course she must take and told her what steps she must take if she wished to return to the sunny coast.

The wine glass slipped from her fingertips and shattered on the marble floor. Amalie gasped. Her eyes fluttered open. In a panic, she stepped out of the tub and cried in agony. Blood pooled around her feet. She pulled on a terrycloth robe and, leaving a pair of red footprints on the white marble floor, limped over to the toilet. Using a pair of tweezers and turning her eyes from the double-vanity mirrors, she plucked tiny shards of glass from her pruned toes and the tender sole of her left foot. She grabbed a washcloth to stanch the bleeding, and after bandaging her wounds, she returned to the bedroom, where she opened her overnight bag. She’d had entirely too much to drink. The best thing to do was brush her teeth and go straight to bed. Instead, with that terrible voice still whispering to her, she quickly dressed and left the hotel.

-3-

By the time she returned to the squalid brick building at the corner of Franklin and 45th Street, it was almost midnight. Her left foot stinging with what must have been the onset of infection, she climbed three flights of stairs and tried to ignore the ever-present blare of televisions and the high-pitched wails of children. She could already feel a hangover coming on and made up her mind to call her manager in the morning to say she was taking a sick day. Keeping her eyes trained to the floor so she wouldn’t notice the chipped and faded paint and the water stains on the ceiling, she searched for the key at the bottom of her overnight bag. Even from the landing, she could hear her husband’s snores. They sounded like the deep rumbles of a timpani. Out of consideration for her, he had agreed to sleep in the living room but adamantly refused to be tested for sleep apnoea. “Better to die peacefully at home,” he told her with a pained smile, “than burden you with another problem.” But this was not their home, and there was nothing peaceful about this place. Five years ago, when they sold most of their possessions and left West Hollywood, he promised her this teaching job in Cleveland would be temporary. Any day now, any minute, the phone would ring and one of the big studios would make him a lucrative offer.

Amalie unlocked the door and caught the sour smell of Daniel’s illness. In the narrow hallway, blocking her path, she found a basket overflowing with freshly laundered linens. They’d go unfolded for days, just one of the many chores their 12-year-old daughter refused to do. Like a fairy tale troll that crept from its fetid cave only after sundown, Layla spent most of her time in a tiny bedroom facing the back alley and spoke to her parents only when necessary.

On the sofa in the living room, Daniel tossed and turned. With each shallow breath, his wasted body seems to vanish beneath the blanket. She gazed at the assortment of pills lined up on the coffee table – Platinol, Taxotere, Tramadol, Megastrol – and touched his chest. In the yellow lamplight, he looked more than pale. He was positively translucent. What little hair he had left grew in thin, wiry patches. Now, without opening his eyes, Daniel lifted his head from a pillow and groggily asked if everything was okay. She apologized for waking him and said she met her colleagues after work for a few drinks. An impromptu retirement party. Someone from human resources.

He smiled faintly and said, “You deserve a night out.”

She knew it was absurd to hold him accountable for their present circumstances, this terrible act of God, but the reality was that, instead of fulfilling his destiny and composing for the silver screen, he had settled for an easy life as a middling academic who occasionally had the honour of conducting conservatory students. For this reason alone, she had grown to resent him.

Outside, a mournful autumn wind whistled between the buildings, rattling the cracked and dirty panes of glass. Situated behind the limbs of a birch tree, the front window faced an abandoned brick warehouse that didn’t allow for much streetlight. She imagined that she had come to a hollow place in the earth, a cave deep in a mountain wilderness where shepherds took refuge from storms and where grieving families came to bury the bones of their beloved dead in limestone ossuaries inscribed with prayers to the Almighty. She remembered then that she had left the book about Beethoven on the hotel room nightstand.

Shaking her head at her thoughtlessness, she draped a blanket over her husband and told him to go back to sleep. All was well. Since she wouldn’t need the apartment keys anymore, she left them on the coffee table and said she’d be right back. “Forgot something. I won’t be gone long.” She retrieved her overnight bag in the hallway and then, for a final time, made her way out the door.

About Kevin Keating

KEVIN P. KEATING's first novel "The Natural Order of Things" (Vintage 2013) was a finalist for the Los Angeles Times Book Prizes/First Fiction award and received starred reviews from Publishers Weekly and Booklist. His second novel "The Captive Condition" (Pantheon 2015) was launched at the San Diego Comic-Con International and received starred reviews from Publishers Weekly and Library Journal.

- Web |

- More Posts(1)