You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

The timing of Sequoia Nagamatsu’s debut novel, How High We Go In The Dark, might be perfect, or terrible. Sold as a literary helping of science fiction and dystopia, the novel focuses on the various ways in which individuals, institutes, and wider society respond to the spread of the “Arctic plague,” a virus which has created a global pandemic with no apparent end in sight. Medical interventions prove negligible, and the abundance of death force people to find new ways to live. But what if the response to death is even darker and more macabre than anything the Grim Reaper could have dreamt?

Though told from an eclectic army of perspectives, the novel begins with Dr. Cliff Miyashiro, a scientist stationed in Siberia who is investigating “the thirty-thousand-year-old remains of a girl.” He is continuing the work of his daughter, who died while engaged in the same task, and it is not long before his mind wanders to his family: Clara, the daughter who is dead, but also his wife, Miki, and his granddaughter, Yumi. “Our daughter never seemed to need us,” Miki observed shortly before Cliff set off on his quest. “But Yumi does.” And so begins this novel’s love affair with bleakness. The rest of the chapter sets the tone for the book. Cliff reminisces, wondering if he should have made this journey at all. He left Yumi sobbing at the airport, and Miki asked him again if he was “absolutely sure about doing this.” In between these trips down memory lane, he also interacts with the other researchers at the site and makes a fateful discovery – a new virus, released from melting permafrost.

The virus is the catalyst for all the misery and despair that follows, but whether the virus is the sole cause can, perhaps, be questioned. The problems that many of the characters face run deeper than the imminent medical emergency – emotional chasms between parents and children, scepticism toward authority, the development of new technologies that make a possible return to normal human interaction even more remote. With that said, the effects of the virus are widespread and devastating. As one researcher explains: “It’s like the virus is instructing the host cells to serve other functions [. . .] brain cells in the liver, lung cells in the heart. Eventually, normal organ function shuts down.” The virus goes a long way to giving the story its sci-fi credentials, and the world’s response gives it a dystopian aesthetic. However, as far as science-fiction goes, Nagamatsu is no Michael Crichton; the virus, and technologies relating to it, are present, but not tangible. Perhaps this is the inevitable result of a book that is clearly more interested in poeticising its characters and their actions.

To the extent that How High We Go In The Dark can be called a single narrative, the “Arctic plague” forms its backdrop. It is worth noting that Nagamatsu is an established short story writer, and it would not be a stretch to read this novel as a collection of short stories bound together by their shared infection. They occur over a long period of time, documenting how various characters try to live in a world ravaged by the Arctic plague. It is clear, from the deeply personal voices encountered in these stories, that Nagamatsu wants to show how people can retain and repurpose their goodness – in other words, how high humanity can go in the dark of a plague-ridden world. So we encounter a comedian who wants to give infected children some joy before the end, an artist who seeks to capture the spirit of settlers escaping earth for Proxima Centauri B, and a doctor who wants to ensure that those struck down by the virus did not die in vain – “ I hope my research can help someone, someday[.]” Many of the characters are definitely motivated by a desire to “help”, and there are some moments of heart-warming camaraderie, such as when a man, who has woken up to find himself, along with many others, in a large, dark room, persuades his fellow prisoners to create a human pyramid in an attempt to escape their captivity. As with many of the narrators in this book, Nagamatsu takes the time to develop the young man, who, as a child “rarely spoke in class,” but “wrote constantly.” Sometimes, his mother would ask him when he is going to get paid for his writing. His reply captures the artist’s contradictory sense of confidence and self-doubt: “Soon [. . .] Art takes time. It’s all about finding the right people who get your work. It’s very complicated.” These little bursts of humanity constitute Nagamatsu’s attempt to redeem a world destroyed not just by an out-of-control virus, but also by the effects of climate change. In a later story, we learn that “The ocean claimed the tip of Florida.” Human ingenuity is put to good use: VR allows people to stay connected even when they are separated, and “robo-dogs” provide companionship to the lonely. But can technology ever be enough? “[Y]ou want your wife back, not her voice trapped in plastic.” Vaccines only mildly alleviate symptoms, and even when the plague is brought under control, “[scientists] couldn’t cure the cancers that emerged after the virus.” It is in these moments where Nagamatsu’s symphony of characters are supposed to lighten the mood, to imbue humanity with a resurgent spirit. Sometimes, they achieve this. Other times, they only wallow in darkness. I do not wish to follow the Emperor who accused Mozart of using too many notes, so I will not suggest that Nagamatsu uses too many characters. Though maybe his impressive cast could be more emotionally diverse. Many of the voices carry the same weight of woe, the same depressive exhaustion. Basking in the depressive can work. J.M. Coetzee is famous for masterfully capturing the bleak, and Michelangelo Antonioni even succeeds in beautifying it. But whereas Coetzee and Antonioni explore their subjects at a distance, detached and disinterested, Nagamatsu takes the reader deep into his characters’ minds, making full use of first-person narration and detailed reflection. When characters are so meticulously drawn, there is a need for them to, at least partially, transcend their misery, but this transcendence of misery is rarely achieved in the novel.

What is fascinating about this novel is the various ways in which society as a whole deals with existential crisis. The creation of “an amusement park that could gently end children’s pain” – in other words, a euthanasia centre disguised as a theme park. Using the body of a pig to grow human organs, only to face an ethical dilemma when the pig begins to talk. Deploying robots to combat loneliness. There is no mention of Ray Kurzweil, Virgin Galactic, or Elon Musk, but Nagamatsu’s future is modelled on their insights, achievements, and vision. One might be tempted to also connect the Arctic plague with COVID-19, and maybe Nagamatsu had that intention when he wrote the book. But the Arctic plague is not COVID-19 – even the most doom-laden messages from the WHO have not suggested that COVID can transform your heart into a tiny brain. Nevertheless, there are some moments that call to mind the COVID era – a man in quarantine says, “They can’t keep us here if nothing is wrong with us”; a sick woman points at the people in masks around her and says, “I want to see you.” If anything, Nagamatsu shows how a virus can infect not only the human body, but also the body politic. In the midst of this societal infection, individuals must develop a metaphorical immunity – “ we’ll find another way to occupy the dark, figure out how to fill it with all that we were and all that we know, now that we’ve been separated from the slog of life.” The solution does not lie in cutting edge technology, which is shown to be of minimal effectiveness, but in the resilience of people. The trouble is, this resilience rarely reaches higher than the odd gesture, which is inevitably lost in a sea of suffering. How high can we go in the dark? Not, it seems, high enough.

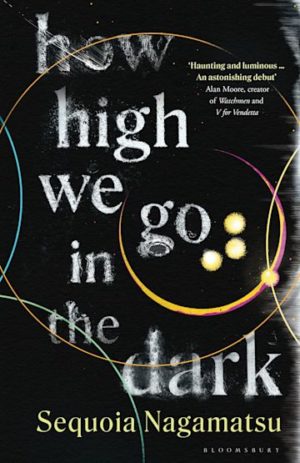

How High We Go in the Dark

By Sequoia Nagamatsu

Bloomsbury, 304 pages

About Robert Montero

Robert Montero is a London-based writer whose work has appeared in South Bank Poetry and London Grip, among others. A novel he wrote was long-listed for the Exeter Novel Prize.