You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

Allison Markin Powell is a literary translator, editor and publishing consultant based in New York City. Powell has been awarded grants from English PEN and the NEA, and has translated works by Osamu Dazai, Fuminori Nakamura, Kanako Nishi, and now, Shiori Ito, whose Black Box has just been released. She was awarded the 2020 PEN America Translation Prize for The Ten Loves of Nishino by Hiromi Kawakami. Powell began working as a translator after completing her master’s in Asian Languages at Stanford University.

Ingrid Petty: Tell me about your background, and how you were selected to translate Black Box.

Allison Markin Powell: I am a full-time freelance literary translator. I mostly translate fiction, but I have translated biography, nonfiction, manga – I’ve even translated embroidery books. I translate all kinds of books from Japanese to English.

IP: Manga?

AP: It’s a form of comic or graphic novel which has a long prehistory in early Japanese art.

IP: And how did you find Shiori Ito’s book?

AP: I’ve worked in book publishing for many years, so I have an extensive network. I’d been looking for a memoir to translate from Japanese for a long time. The thing about memoir is…we know it as this established genre – I mean “we” as in English-language publishing in the US and the UK – memoir as a tell-all form. We just sort of lay it bare. And that’s not really the Japanese way. Memoir has been developing for decades into what it is now a very successful genre for us as English-language readers. Reading other people’s stories resonates. For me, in particular, I enjoy reading memoirs, so I was thinking I’d really like to translate a Japanese person’s story that would resonate. But I found that there just aren’t many available.

And the thing is, if the Japanese do write memoir, they’re not as candid as what we would expect; that’s the societal norm. In Japan, acceptable forms of self-expression, both psychologically and emotionally, are quite different. Writers in English get very personal.

IP: And what are your thoughts on Shiori’s book as memoir?

AP: So, as I said, I’d been keeping my eye out for a memoir. And then I saw Motoko Rich’s profile on Shiori Ito in the New York Times in December 2017. I had heard about Shiori’s story, but that was the first time I learned more about it being put out there; Black Box was published in Japan in October 2017. That’s also when the news broke about allegations against Harvey Weinstein in the US. So it was really by coincidence of timing that Shiori’s story became so symbolic of the #MeToo movement and catapulted her to another level of visibility. I mean, she had been fighting this battle on her own for years already.

IP: Yes, her experience with Mr. Yamaguchi happened in 2015, and she fought the battle with the investigation and the courts and even with the media throughout that time and then more so after her book was published.

AP: I can say, Shiori is singular in the way she lays things bare. What do I think about it? Black Box is not a rape memoir, if there is such a thing. It’s a “tear down the system” manifesto.

IP: That’s exactly what I got from it. Her story is less about her story than it is about her objectives to reveal that there are no supports for women who suffer sexual assault in Japan.

AP: Right. Every institution failed her, even the hotline that was supposed to be the initial source of support. To me, that’s also very emblematic of the way things are in Japan. They set things up, but the structures are not flexible enough to meet people’s needs. I was really drawn to not only her struggle, but to her personality and strength.

IP: How did you come to be a translator of Japanese?

AP: I’ve been working as a translator for a long time. I worked in publishing before that. I started studying Japanese when I was in college. I was eighteen when I started, which is late for English speakers to learn Japanese – it’s a very difficult language.

IP: But you never lived in Japan?

AP: I did. I studied there. I did an exchange program as an undergrad; I spent six months there in different programs. And I spent another year there before grad school in the States to study Japanese literature. I go back to Japan regularly, because really a year and a half is nothing, not at all an extended period of time to have spent immersed in Japanese culture and society.

IP: On that subject, Ito mentions in her book that Japan is a safe place to live, but for women, not so much, because of the practices of men and the fact that women have no voice; they are just meant to take it. Did you have any experiences along those lines that may have been disturbing for you?

AP: You know, the part she wrote on “chikan” – public groping – it was astonishing to me, the way she just laid it out and presented it for readers to make the connections. About how early it begins in a girl’s life, and – I don’t want to say it’s acceptable – but it’s just part of society. And, yes, it happens. That happened to me; it happens on the subway. It’s hard to imagine there is a female there to whom it hasn’t happened. Of course we have that in New York City, too, but you know, it’s just not as prevalent. In Japan, it’s almost like a fact of daily life, but nobody talks about it. And the way that Shiori puts it in at the end of her book…I thought that part was really searing, the way that she describes her own experiences with it. I think Granta is going to excerpt that part of the book, so I’m happy about that.

IP: Tell me about your work with Words Without Borders.

AP: Well, I served as a guest editor for their first Japan issue, many years ago now. Words Without Borders is one of the preeminent online literary journals of international literature. They do amazing work, and I’m always happy and excited to work with them about Japanese literature. I know some of the founding editors and the editorial director. I keep in close contact with the people who work there. I also work with PEN America. I do a lot of advocacy. I was cochair of PEN’s Translation Committee, and now I serve on their Board of Trustees. It involves working with a lot of other translators and organizing events. And I have my database Japanese Literature in English, which is currently somewhat neglected, but I hope to get back to updating soon.

I do a lot of advocacy around working conditions for translators, too…translating is not a particularly lucrative field. Like, for what I do…it took me a long time to acquire enough knowledge in Japanese language and literature in order to do this work; and yet our pay scale is not commensurate with the skill and expertise required of translators.

IP: So, other than the fact that you were looking for a Japanese memoir to translate, how did Black Box come to English language translation? I know it has already been translated into other languages.

AP: The publisher of the Japanese edition was interested in selling the rights around the world, and I know the people in the rights department, I had been in contact with them for other works. In the summer of 2018, they contacted me about preparing a sample translation and other materials. And, as it happened, Shiori was here in New York. It sort of happened at the last minute, and that was really a great opportunity, because we got to meet in person.

And I remember when I was translating the sample – I translated about twenty-five percent of the book as a sample, a pretty big chunk of it – but I was doing that during the Kavanaugh hearings that were going on. And that was difficult, in its own way. We all went through that, as a country. So that was my first experience of what translating Shiori’s book would be like – I mean, of course I realized that translating it would not even compare to the trauma that Shiori has been through and continues to go through. But it was a taste.

And then PEN has its international literary festival in the spring each year called World Voices. Since I work with PEN so closely, I had told them about Shiori and her book. The book wasn’t under contract yet, but when I told them about her, they were thrilled and immediately invited her. She participated in that festival, in the spring of 2019. She came and spoke on a couple of different panels, and while she was here, we met with some editors to try to place it. That’s when we met with The Feminist Press. It has been kind of a slow process, to be honest. Book publishing is not usually very fast-moving.

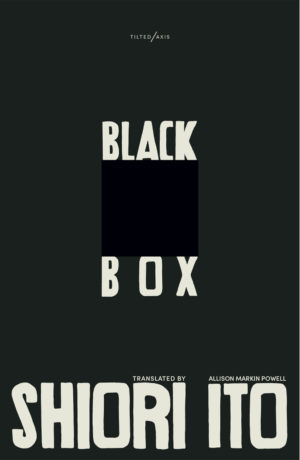

So, The Feminist Press acquired it in the US, and Tilted Axis Press acquired it in the UK. They are both non-profit publishers. Tilted Axis specializes in women writers from Asia; this is their first non-fiction publication, which is kind of a big deal. They also have a new series called Translating Feminisms, and this was a natural fit for them.

IP: OK, but now I’m confused. When I see the English translation of Black Box on the shelf, will it be published by The Feminist Press or Tilted Axis Press?

AP: Well, you’re reviewing the book for Litro, so you’re reviewing the UK edition. And where are you based?

IP: I’m in Texas.

AP: Then, when you see the book on the shelf there, in the bookstore or in a library, you will see the US edition published by The Feminist Press.

IP: Ah, I see. So, back to when you met with Shiori – you were obviously impressed with her ability to stand up and speak out – but was there anything else about her you’d like to comment on? What were your thoughts on her as a person?

AP: What was noticeably unique about her, as far as Japanese women go, having spent as much time as she did abroad…well, it’s not even that. She writes in her book about being in the hospital when she was a young girl, how it took her out of her school environment and out of that “race” for prestige in Japan. She wants to learn; she wants to be a journalist; she wants to earn a living. She wants to be a part of society, but it’s not so much about acquiring the markers that many other girls her age are traditionally interested in – material things, or stereotypically girly things.

And she has an affinity for older people. I think it’s unusual for such a young person to forge these connections with senior citizens. She sees people’s humanity. I haven’t spent a lot of time with her, but even so, I got that from her.

IP: Well, she seemed awfully determined, and knew what she wanted, even at a very young age, and worked hard to make it happen.

AP: She certainly was very resourceful in finding ways to go about becoming a journalist, you know, going to this university…and then finding this study-abroad program here…and oh, while I’m here, I’ll learn Spanish…oh, I can go to Syria, maybe I’ll pick up Arabic. You know?

IP: She took these detours, but she got a lot of experience.

AP: Yes, she gained something from each one of them. I mean, we see that she is fearless, and I think she was fearless all along.

IP: Maybe not the kind of girl Mr. Yamaguchi expected.

AP: Yeah, one of the things…it took some time to get my contract settled with the publishers to do the translation, so that didn’t happen until right before the pandemic began. And like I said I had translated a quarter of it already – I thought I had done a lot of the hard parts, the incident itself and some of the aftermath. But I was still unprepared for how difficult it was going to be – I mean, it was a very difficult book to work on, period. But even more so, it was a very difficult book to work on during the pandemic.

I’m not in any way equating translating it with the experience that Shiori went through, but it was its own kind of trauma, to sort of be in that book and translate the language. I felt like the book was a vortex. I had to figure out ways that I could get into it in order to translate it, but then step out of it, so I wasn’t carrying it around with me all the time. And obviously, for a victim of assault, they have to live with that all the time. They can’t step out of the vortex, really.

In the other three-fourths of the book that I was working on – the emails between her and Mr. Yamaguchi, and then the investigation, and the prosecution – all along, everybody was trying to gaslight her. And that was really upsetting and disturbing to me. It was a real challenge. I have translated nonfiction before, but I’ve never translated a story that was this traumatic and this difficult. As a translator, you sort of inhabit the work that you’re translating. Black Box was not an easy book to inhabit.

IP: That’s a good point to make, from your perspective.

AP: I can’t wait to see what English language readers think of it.

IP: It comes out June? July?

AP: The Tilted Axis edition comes out June; The Feminist Press edition in July. I don’t know if you saw that the launch event in the US will be with Chanel Miller, who wrote Know My Name? When Shiori and I were talking about the publicity for Black Box, when I asked her who she’d like to be in conversation with, Chanel was her number one, dream choice. We were able to reach her, and she agreed to do the launch, so I’m really excited for that event. Chanel mentioned that when she did publicity for her book in the UK, journalists asked her about Shiori, who was living in London at that time. Chanel was surprised that she hadn’t come across the book – well it hadn’t been translated yet. So, when we sent her the Black Box manuscript, she was happy to be able to support Shiori.

Shiori is currently making a feature-length documentary of her story. A lot of what’s in that film is in the book.

Time named Shiori one of the 100 Most Influential Women in 2020. She and Naomi Osaka are the only Japanese people – Japanese women – on the list.

IP: Well, thank you. You’ve given me the back story I was looking for, and your impressions are helpful as well. Can you tell me about Strong Women, Soft Power?

AP: Yes, Strong Women, Soft Power is a collective of translators of Japanese, all women; Lucy North who lives in the UK, Ginny Tapley Takemori, who is in Japan, and me in the US. We decided to band together to promote Japanese women writers. When you look at fiction writers, Japanese women writers seem to be having a moment now, they have a lot of clout. Many of these women being published in English – there are both long-standing and very well-regarded writers as well as new and up-and-coming writers – are getting a lot of attention. In Japan, they’re winning literary prizes and their books are among the bestsellers. I’ve done the research, I’ve collected the data, and in both of these areas, it’s close to parity with male writers. But then when you look at the books that have been translated into English, the women are trailing – it’s between twenty-six to twenty-nine percent in any given year. So, where is the disconnect, who’s at fault? We’re still trying to figure that out. And we’re working to bring that disparity to people’s attention. We’ve done a symposium, we write articles, we hold events, we’re curating an author/translator event series online right now.

IP: Well, you’re doing good work. I think anything that serves to move things forward for women, and especially for those being suppressed, is well worth the time and effort.

AP: Yes, it’s gratifying work. It’s kind of remarkable how much the problem persists.

IP: And we appreciate you. Thank you for taking time for this interview.

AP: Thank you, Ingrid.

About Ingrid Petty

Ingrid Petty is an author of narrative non-fiction and aspiring memoirist based in San Antonio, Texas. After a career in law and philanthropy, she wrote her first book, "The Kronkosky Foundation Story: Creating Profound Good through Community Philanthropy," published by Trinity University Press and Maverick Books in November 2021.

- Web |

- More Posts(2)