You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

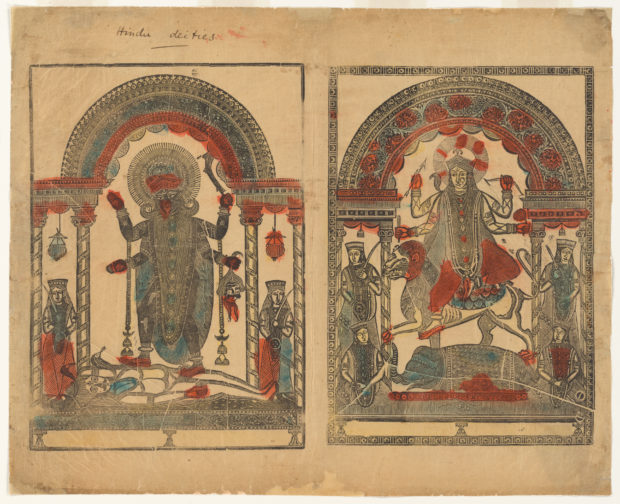

In the place I come from, once the moon resumes its light in the Hindu month of Kartik, the Odiya people worship goddess Kali. Sculptors carve out scores of images in the hope that they have managed to give their handiwork a whisper of pulsing life. In temporary shrines the priests in ochre garments wave a camphor flame in front of the image of Kali, and chant prayers in the praise of the deity. Devotees pour in to offer goddess Kali red hibiscus flowers, rice and lentils. I now stand in one such shrine, staring fixedly at the consecrated image of Kali, stunned by the sublime impression it has made on me.

The somber bong of the bell, the brass tone of the gong, the shrilly clank of the hand cymbals and the resonant sound of the steady hand-clapping harmonize to produce music that echoes through the shrine, making the deity’s presence felt. Numerous mud lamps cast shadows on Kali’s gaunt, terrifying visage, endowing it with a certain haunting quality. However, one feature of the clay sculpture in particular concentrates my attention – Kali outstretching her tongue upon standing on the supine body of her own consort Shiva. This detail unlocks the attic inside my mind, letting out shuttered memories that fold their wings like owls, ambushing my unwitting self. I remember my mother telling me a story, when I was a child, about how Kali once salvaged a desperate situation by defeating some demon, upon being summoned by the gods. After killing the demon, Kali lapped up its blood which drove her berserk, my mother said. Stirred up with blood-lust and rage, Kali then went on a rampage, laying waste to the planet. So the gods beseeched Shiva to placate her. Shiva hatched a plan. He lay recumbent like a corpse under the thrust of Kali’s heel, waiting for her to come to herself. Aghast at the realization of what she had done, Kali bit her own tongue out of shame. Needless to say, if there is any lesson the tale imparts, it is this that a woman who allows her darker and wilder side to take possession of her is not quite a woman. Even as a child, I cared very little for this tale, or for that matter, any instructional tale that taught one what to be like and what not to be like, for one was expected to drink such a tale like some medicinal syrup, without asking any questions. I had expected for this tale to be upstaged by other tales or recede in my mind over the course of time, as is generally the case with children. But the tale still floats dim through my mind for my mother always foists it upon me, anytime she seems to think that I have forgotten the golden dictum.

Even the man, I thought I cared for, took it upon himself to redress the brash nature of my spirit, to reign me in, as he liked to call it. He once told me that he could hear the wind in me, its brute cry of abandon. He feared that my wind would winnow through the crumbling house of him, unhinging and shattering his windows and doors of reserve, making his fire of longing roar and thrive. So in a patently surly voice he called me crazy. His words, the thrust of disgust in the timbre of his voice sowed the seeds of self-loathing and shame that took root and grew within me, taller and thicker every year, like some bamboo hedge, keeping in check, the wind that blows within me turbulently. And in the process, that bold, uninhibited and self-assured woman who rippled with life, the woman that I once was in the distant past became just another stranger I didn’t know.

But today I have come into my own for what I see now before me is the naked splendor of Kali’s bravura that occults that cobwebbed lore from my childhood. The majestic features of the deity overwhelm me: her disheveled hair, her eyes blazing like a shooting star and her unashamed tongue lolling out from the great zero of her mouth, ease my confines, and free my soul from its terrible prison.

I feel alive again. Rage displaces shame. Incapable of living against my grain, I burn in my own soul fire, feeling the intense unction of its yellow flames that tongue change. Born anew, I rise from the ashes, tongue unfurled like Kali to destroy my own inner demons and slurp on their blood.

About Rituparna Sahoo

Rituparna Sahoo is a writer and poet from Bhubaneswar, India. She writes about relationships, trauma, abuse and grief. Her work has appeared in Wild court, Ink Sweat & Tears and Eclectica.