You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

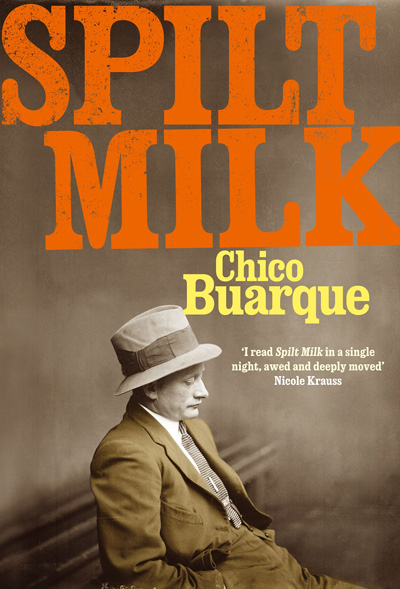

It’s not often I get to the end of a novel and realise I need to reread it straight away. Not just because I liked it—I did—but because I realised this isn’t the novel I had thought it was at the beginning, halfway through, or even near the end. At first glance, Spilt Milk by Brazilian author Chico Buarque doesn’t sound like it should be particularly complicated, intriguing, or moving, but it is.

Eulálio Assumpção is a pedantic centenarian who has taken it upon himself to relate his riches-to-rags tale from his hospital bed. A member of the crumbling Brazilian aristocracy, he tells his story in a wilfully rambling fashion in long, unparagraphed monologues, generously peppering them with mildly snobbish and racist language. No, thank you, you might think, not my kind of narrator. Hang on in there, though, and read on, because Eulálio will somehow charm you, and before you know it you’ll have gone and fallen in love with him, his story, and Brazil.

At first, his story begins slowly: “When I get out of here, we’ll get married on the farm where I spent my happy childhood,” he tells a nurse, grumbling that “she’s in a sulk.” His mind wanders back and forth, slowly and confusedly. Memories of his past—playing with the descendants of slaves on his family’s farm, his father’s sudden death, his time in France amongst prostitutes, the first time he saw Matilde—swell hopefully before breaking against his present situation: hospitalised, bedridden, and alone. But there’s no easy distinction between past and present here; the former bleeds sleepily into the latter, oozing a trail of sinuous, slippery memories that we revisit again and again, each time slightly different from before.

The effect of these wandering, accumulative recollections is confusing. Where is Matilde now? Did she run away? Did she die? What happened to Eulálio’s father? Didn’t Eulálio say he was murdered? Is his mother really still alive? Wasn’t it the other grandchild who lost the family’s money? From this narrative disorder eventually emerges a delicate portrait of an upper-class Brazilian family, complete with ancestral slave traders, colonial lords and corrupt politicians, whose socioeconomic demise is set against the backdrop of Brazil’s recent history. Eulálio may be a product of his own background—spoilt, pedantic, proud, snobbish and racist (he says things like, “It may well be a step forward for Negroes, who only the other day were sacrificing animals”)—but he is not just a symbol of the obsolete aristocracy. He is also warm, funny, brave and honest—an unintentionally likeable person whose subtleties we come to understand better the deeper we delve into his head.

It is the very nature of memory that lies at the heart of this novel. What does it mean to remember something? How do we order our memories? How can we trust them when they begin to falter? And how do we know if what we are remembering is a true memory, or just a “copy of a previous one”? Slivers of half-formed memories begin to take on significance as Eulálio repeats stories with new details each time, but the most mutable story of all is that of his relationship with Matilde: the girl who slipped into his life as quickly as she slipped out, like a cat.

It’s strange having memories of things that are yet to happen; I’ve just remembered Matilde’s going to disappear forever.

There is a deep melancholy in this crotchety old man’s recollections of his young, impulsive and beautiful wife. It seeps silently into the story, so that it is only at the close of the novel that you realise you have been reading a tragic love story all along. We never find out what happened to Matilde—whether she ran away, had an affair, died, or killed herself in a mental hospital—but the memory of the cinnamon-skinned girl with “Moorish eyes”, who stole his heart in church one day before disappearing forever, is one Eulálio cannot forget.

Despite this terrible sadness, Spilt Milk is very much a celebration of life and survival. Eulálio may be an unreliable, irritable and blinkered narrator, but he also tells his story with an affable matter-of-factness that imbues it with joy and humour, devoid of self-pity. The novel’s great strength is in its gradual, rhythmic development; it slowly builds a detailed, layered portrait of a unique man and country, memory by memory. Even if, like me, you don’t initially notice some of the detailing and patterns, it is hard not to appreciate the skilful English translation by Alison Entrekin; such an intricate novel could easily have lost something in the process.

Spilt Milk, however, isn’t the easiest of reads. Eulálio’s confused voice and tangled narrative initially make for slow, laboured reading. It is only after a good few chapters that you might begin to unpick parts of his story and make sense of what he remembers. Indeed, at first this threatens to be a dreary novel about nothing in particular, but read on. Look for clues and patterns, let the novel build up around you and establish its simple foundations. Only then can you appreciate its hidden, complex architecture. Read it and then reread it.

First published in English on 1 October 2012, Spilt Milk is currently available in hardback and ebook by Atlantic Books, UK and Grove Atlantic, US. The Portugese version, Leite Derramado, was published in 2009.

Thanks to Atlantic Books for our review copy.

You can find more of Chico Buarque at www.chicobuarque.com.br.

About Bella Bosworth

Bella Whittington reads and reviews a bit of everything, but is particularly interested in literary fiction, translations and short stories. After living in Spain for a year, she now works as an assistant editor for Transworld Publishers in London. She has also contributed to Thresholds, the University of Chichester's international short story forum, and the Harker.

If you want to know what happened to Matilde, keep looking. The clues are there.

(Don’t worry, it took me a while too – and I’m the translator!)

A.E.

Thank you for letting me know – I think this demands a third reread!

This novel is really very nice. I read this. Thanks Bella Whittington for sharing. google play codes

I like your amazing post.thanks for share this with us.

Good and full of knowledge.