You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

“If you’re having number problems, I feel bad for you, son…

I got 99 problems but maths ain’t one, hit me!”

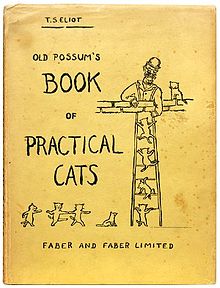

Sound familiar? That rapper Jay-Z? Was it really maths he was rapping about? It’s 99 Problems by Harry Baker and despite the arm swinging, there’s no music – it’s not rap, it’s spoken word poetry. Poetry is turning musical and I don’t mean Cats (though that particular musical is based on T. S. Eliot‘s poetry collection Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats). Poetry started out lyrical, and since the 60s it’s been heading back to where it started. Spoken word is the perfect example of the fluidity between music and poetry.

In Harry Baker’s parody/homage to Jay-Z’s 99 Problems it’s maths that he can handle, not Jay-Z’s “bitch[es]” – in fact, from the looks of him, he has all sorts of problems with the latter. And while I doubt there is more than one way to read that particular piece of spoken word, Baker is a heavyweight on the poetry slam stage. It may be a small word but he’s at the forefront of it, from London Slam Champion (2010) to UK Slam Champion (2011) and onto World Slam Champion (2012).

“I got my… calculator on statistics mode / Pencil and protractor and I’m ready to go / They say that I’m a looser with no life and no hope / But I’m a mathematician what types of facts are those? […] / If I don’t fit in, well I don’t give a… standard deviation / They call me the denominator / Because I defy crowds like hyperbolic equations, yeah […] / But from fractions to decimals, we ain’t done / I got 99 problems but maths ain’t one, hit me! / If you’re having number problems, I feel bad for you, son” 99 Problems, Harry Baker

Sound Poetry

Though spoken word is not performed to music, in that particular work, it’s impossible not to hear Jay-Z’s music in your head, and that is the whole point. The musicality of spoken word is intentional – the way the artist performs the piece functions in lieu of music, so that it doesn’t need to be there to be heard. Going one step further, its precursor, sound poetry – fathered by Futurist and Dadaist vanguards – bridges the gap between literary and musical composition, the sounds actually replacing the words: it is verse without words.

Obviously, it is intended primarily for performance, and experiments in that art form have had varying degrees of success. With 32 minutes of different families of coughs, Yoko Ono’s Cough piece (1963) is one example, and she went on to ‘pen’ Toilet piece (1971). Sound poetry may seem like a very niche sort of poetry, but if you’ve ever been to a party where the hosts has played ‘ambient fireplace’ or ‘sounds of the sea’, then you’ve heard a commercially produced version of sound poetry.

Obviously, it is intended primarily for performance, and experiments in that art form have had varying degrees of success. With 32 minutes of different families of coughs, Yoko Ono’s Cough piece (1963) is one example, and she went on to ‘pen’ Toilet piece (1971). Sound poetry may seem like a very niche sort of poetry, but if you’ve ever been to a party where the hosts has played ‘ambient fireplace’ or ‘sounds of the sea’, then you’ve heard a commercially produced version of sound poetry.

Some sound poetics were used by later poetry movements like the Beats generation in the 50s or the spoken word movement in the 80s. Artists like Gil Scott-Heron brought it to the forefront with pieces like The Revolution Will Not Be Televised. If poetry and music have sometimes been criticised for not being current enough and lacking a message, spoken word certainly cannot be challenged on these grounds.

“You will not be able to stay home, Brother / You will not be able to plug in, turn on and cop out. / You will not be able to […] skip out for beer during commercials / […] Black people / will be in the street looking for a brighter day. / […] The revolution will not go better with Coke. / The revolution will not be televised” The Revolution Will Not Be Televised, Gil Scott-Heron

Music democratising poetry

I saw slam poet Harry Baker’s performance poetry in a pub in Borough at Bang Said the Gun, an event which describes itself as a “poetry night for those who don’t like poetry!” We can deplore the sad state of the public perception of poetry when marketing like “It’s poetry, not ponce” and “it’s like mud wrestling, only with words” is what draws the crowds in, but ultimately performance poetry has done a lot to revive interest.

According to the Independent: “if the spoken word has long been misunderstood as an art form – hovering between poetry, comedy and theatre – that is slowly changing. This is the first year [2012] it has merited its own section in the Edinburgh Fringe programme, while performers such as Luke Wright and Kate Tempest have been gathering mainstream followings.” In fact, Tempest has won the 2013 Ted Hughes Poetry Prize, which rewards innovation in poetry, and while the world’s biggest poetry slam, National Poetry Slam, takes place in the US, spoken word events are popping up all over London. Spoken word and poetry slam (performance poetry contests) allow poetry to be shared, to become a social activity, as well as carrying a social message. Spoken word is talking poetry that gets us talking about poetry.

Money makes poetry go around

US poet Robert Frost told President Kennedy: “Poetry and power is the formula for another Augustan Age” to which Kennedy agreed in a thank-you letter: “It’s poetry and power all the way!” And poetry may well still be a symbol of power in the US with Richard Blanco becoming the fifth poet to read at a US presidential swearing-in (at Obama’s second presidential inauguration), in a tradition kick-started by Frost himself – who read for Kennedy.

But if ‘money is power’, the opposite is not true: even though poet is recognised as job, with the US Poet Laureate receiving over £23,000 a year for his efforts, it’s not exactly an extravagant living, even for those at the very the top. Meanwhile, UK Poet Laureate Carol Ann Duffy gets the job for 10 years, but she couldn’t live off her yearly poet laureate stipend of £5,750. In comparison, Scots belie their reputation as misers with the Scottish national poet, the maker, receiving a £10,000 annual stipend.

What it boils down to is that in the poetry world, even the top dogs need to supplement their royalties – which is to say earn a living. The “practical cats” earn royalties from their poems being recycled into songs but they are the lucky few. Others depend on teaching poetry and readings. So live events like poetry slam which are lively and attract a wider – and younger – audience are a way of doing poetry’s PR: even poets can’t afford to live off love of art alone.

The union of poetry and music has spawned collections of lyrics, sound poetry and spoken word. Whether we like it or not, marriage is the ultimate financial arrangement, and poetry and music are no exception. When it works out well, everyone stands to gain something from it.

“i carry your heart with me(i carry it in

my heart)i am never without it(anywhere

i go you go […]

here is the deepest secret nobody knows

(here is the root of the root and the bud of the bud

and the sky of the sky of a tree called life; which grows

higher than soul can hope or mind can hide)

and this is the wonder that’s keeping the stars apart

Most of us carry some poetry in our hearts, whether we know it (or like it) or not – it could be the nation’s favourite, immortalised on film in Four Weddings and a Funeral: W.H. Auden’s Stop All the Clocks, a poem learned by heart at school, or a favourite song which unbeknownst to us started as a poem (to all TLC fans, if you love their hit Unpretty, you are in fact listening to an improved version of a poem penned by band member T-Boz). As Muldoon remarked to The Guardian on growing up in rural Northern Ireland: “These guys were farmers for the most part, but they could also recite a bit of a Robert Service poem”.

We don’t tend to “carry” poetry on our bookshelves quite so much anymore, however, and poetry can seem inaccessible. As children we memorise verse, but poetry becomes more of a complex beast when, as adults, we have to make sense of it as part of the world around us. In the case of abstract poetry it can be a struggle, possibly because we are digesting too fast – perhaps fitting it into a daily commute, reading Poems On The Underground as it were – a text, which while usually short in length, requires more time than it takes to read it.

Poetry can be a rather slimy beast, a shiny eel slipping between our fingers, and we find we’d as soon be reading prose, or the papers, because, to paraphrase William Carlos Williams, it’s easier to find the news there, in other words we don’t have to work so hard to find a relevance to our daily lives. In my case, “I carry [Prévert] in my heart”. He was a fringe member of the surrealists’ club, so perhaps, it should come as no surprise that his 1946 collection Paroles (which means ‘words’, but also ‘lyrics’) – an eclectic mixture of poems, short texts and songs – blurs boundaries between genres and that is very much part of the appeal for me. Not coincidentally, another poet I carry in my heart is also a songwriter, and as far as I’m aware, he is the only poet alive who can fill London’s O2 Arena. If, like me, you found yourself throwing underwear at a 78-year-old man on Sunday 15 September, you’ll know two things:

1) Poetry/spoken word is integral to Cohen’s performance and it is not going anywhere as long as Cohen is around (The Guardian writes: “Such is the reverence, so eager are people not to miss a beat, that they don’t even sing along”);

2) Cohen is not going anywhere, as he told his London audience: “I’m not quite ready to hang up the boxing gloves”.

Corollary: poetry is not going anywhere. So when you’re ready for a break from Cohen’s greatest hits, Cohen live and Leonard Cohen: 10 Great Cohen Covers, go to the library and pick up his poetry. As for me, after the obligatory read of T.S. Eliot (it was a birthday present from a boyfriend), I’ve just booked tickets to go and see Cats.

Corollary: poetry is not going anywhere. So when you’re ready for a break from Cohen’s greatest hits, Cohen live and Leonard Cohen: 10 Great Cohen Covers, go to the library and pick up his poetry. As for me, after the obligatory read of T.S. Eliot (it was a birthday present from a boyfriend), I’ve just booked tickets to go and see Cats.

Podcast: Embed

Subscribe to Litro Lab via itunes RSS | More

About Clémence Sebag

Clémence Sebag is roamer, she started out as a West Londoner, worked her way up North, then ventured down South until all that was left was East. She tried Rio and Buenos Aires but couldn't get used to the weather. By day she works as a literary translator, by night she writes book reports for a literary scout. She wants to be a writer when she grows up and everybody knows Paris is where writers live. Fall-back career: literary groupie. She Blames Bridget Jones for not having gotten around to penning the 10th draft of her 31st novel. Meanwhile, you can find some flash fiction from her Goldsmiths Creative Writing MA here. She also dabbles in poetry and you can find her in the anthology The Dance Is New. Best place to find her: Café de Flore. If Paris is too far, Tweet her @clefranglaise or follow her blog.

Always learn so much from these articles and come out the other side feeling cultured and smug : ) Great article!

This piece shed a lot of light on the spoken word form for me, I wonder whether perhaps you’ve seen it done badly as suggested in this recent article:

https://www.newstatesman.com/culture/2014/01/why-i-both-love-and-hate-spoken-word

I certainly have, almost always in a pub’s dusty back room – this quote perhaps sums it up …

‘there are artists that use spoken word to introduce young people to

poetry […] Poetry is an art form on the wane,

but the culture of spoken word has reinvigorated it – which is

anything but bad. Even if it does mean putting up with a few wankers

along the way.”