You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

She wakes each night to the same dream. Bathwater spilling over, stealthily onto the floor. It dribbles into the hallway and to the door behind which she sleeps. She wakes crying, and she thinks that perhaps she is the bath. But her tears do not smell of lavender salts, nor do they foam like suds as they fall.

She keeps four loaves of bread in her dresser. Thick white, sliced. She worried that brown bread may have stained the enamel. The radio is still on in the hall. She likes to feel she is the first one asleep at a party. But the illusion is shattered once she steps onto the empty landing, barefoot and cradling three loaves like a bundle of babes. She is careful to keep one spare. Nestled in the dresser in case of catastrophe.

At breakfast, she likes a drink. Fruit punch – heavy on the rum. She calls it rummy, which makes her sound like a child. More rummy in my tummy. That sort of thing. Silly, really. She has her punch and her porridge, and then she washes in a bath filled with bread.

The neighbours complain she has been eating their flowers – the daffs are all beheaded, and their rose beds are a mess. They say she takes whole bunches from the grocers on the corner, as a special treat for Sunday lunch. You’ll never see flowers on the windowsill. Not in her house.

She cut the doorbell cord when she turned sixty. Severed it with a pair of nail scissors she keeps by the kitchen sink. She vomits each time the phone rings and thinks about cutting that, too. She answers it in silence, wiping rummy from her chin.

Her house is like the tropics, swathed in balmy heat that agitates the ripe, green smell. Detergent and warm tomatoes; a little rancid sweetness from a bowl of browning fruit. Her monthly gas bills paper the walls like trophies. Three-hundred-and-twenty-six-pounds-eighty-nine. That was July. She patters around in little more than an apron printed with Matisse’s Large Red Interior, the waist ties dangling, uselessly, at either side. It was a gift from her husband, back when she was twenty and scandalous. He took a trip to the Côte d’Azur while she stayed at home and made a baby with another man. She painted the carpet red on week nineteen, and after that the apron fit as it should.

Her legs bulge beneath the apron like two bristled ham bones, darkening to purple at the feet where veins pucker and protrude. Her toenails, also, are purple – liberally lacquered by her own unsteady hand. She hasn’t a nail on her leftmost, smallest toe – it was lost in her sleep long ago – but she has daubed polish over the skin to give the illusion of a full set. The missing nail disturbs her. She never found it among the sheets.

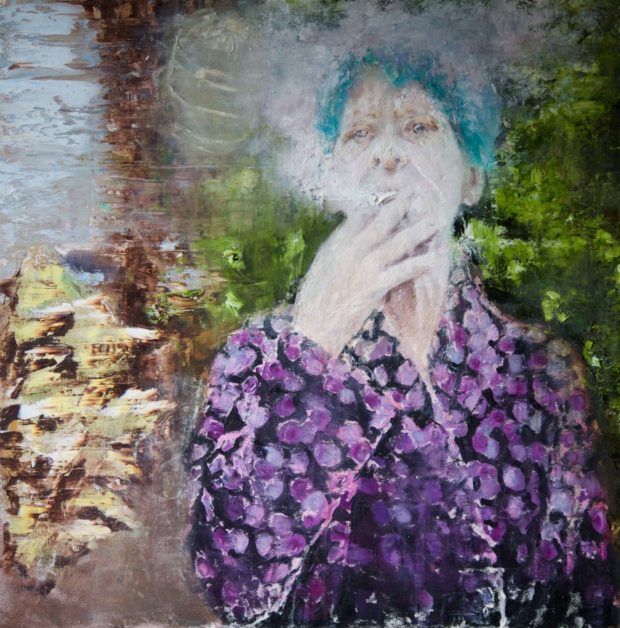

Her large, handsome face is seldom made-up. She doesn’t care for all the fiddling and fuss. But on her birthday, she paints herself as a tigress or a jaguar – caked, exquisitely, in reds and golds and browns. When her time is up, she will be buried as a cat. Her husband was buried as himself. Beige shorts, spotted shirt, grey skin. He ate so much salt it made his brain seize up. That’s what the doctors said.

*

The couple next door don’t say hello. They hear her crying at night and tell themselves it’s foxes.

Perhaps it is the foxes that ruin their flower beds, but they tell themselves it’s the lady who lives next door.

*

On Thursdays, she cleans the house. She throws sodden bread into the garden from the bathroom window. She knows the foxes will have cleared it come morning. It’s warm and marshy in her palms, like the final dregs of porridge salvaged from the pan. The mush smells exactly as it feels, and she wonders whether this is how she feels, how she smells. The doughy parts have fallen away, some congealing in the drain, and she holds the flaccid crusts to her face, peering through them like a toddler in a box of picture frames. She bleaches the drain once the bathtub is clear and then fetches a new loaf from her dresser.

At noon, she dresses in cotton knickers and a housecoat, and lumbers to the grocers at the end of the street. She wears her husband’s shoes, three sizes too big. There are nectarines and cherries piled in crates outside and potatoes in tall sacks that reach her waist. She stands a while, testing the firmness of the fruit with her withered fingers. A cherry ruptures in her grip, and she licks the juice quickly from her thumb, throwing the rest over her shoulder. She goes inside.

The young man behind the counter does not say hello. He watches her closely as she fiddles with a tin of peas before setting them back on the shelf. He has poppy-seed eyes; small and dark and suspicious. She pulls four loaves of white bread from their rack and wrestles them to the counter. She points to a bottle of rummy and adds a packet of bubblegum to the pile. Eighteen pounds and sixty pence. She counts out handfuls of twenty-pence pieces, pushes a stick of gum between her lips, and leaves with a bag tucked under each arm.

At home, she drops her shopping and undresses on the hallway mat. She wriggles the apron over her head and then carries the loaves upstairs. She spits bubblegum down the toilet and flushes. And then she worries that it will clog the plumbing and that the toilet will overflow. It would be terribly impractical to put bread down the toilet. And so she resolves that she will surely be drowned in her sleep or else die from a ruptured bladder if, indeed, she is compelled to fill the toilet with bread.

For dinner, she warms tomato soup in a pan until it is the temperature of a tepid bath. She sweats a little over the stove and brings the hem of her apron to her brow. At the kitchen table, she swallows her soup and listens for the sound of water above.

It is purple and gloomy on the landing as she turns the radio dial. She does not recognise the music. She has placed a saucepan beneath her bed. The toilet lid is sealed with parcel tape, and beneath it is half a white loaf. Outside she hears crying, dirt kicked against a fence. Perhaps she will not be buried as a cat but as a fox.

About Holly Rose Gammage

Holly Rose Gammage holds a BA and an MA in Creative Writing. In 2020, Holly won the inaugural Kurious Arts short story competition, and was longlisted for the Mslexia short story competition. Her short fiction has also featured in Lunate journal, and has been broadcast on BBC Radio.