You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

There’s nothing sweet about the sugar in A Tall History of Sugar, the fifth novel by Jamaican writer Curdella Forbes. Its sweet, sticky menace oozes from the opening pages, mingling with the blood of the slaves who were worked to death to sweeten European tea: “You will see this in the annals of the sugar plantations, how it was that the bright brown crystals came about, how bone and blood got mixed in the métissage, tips of fingers, sometimes knuckles, and even whole arms bitten off by the great machines. The crystals at first wine-dark in blood, then soakaway to brown when the crushers smoothed them out.”

Most of the main characters have some form of extreme reaction to sugar. One has a long-running diabetic sore, another is allergic to sugar in all its forms, and another has a birthmark that gives her excruciating pain every time the sugarcane harvesting season comes around. The lasting violence of sugar and slavery and its intergenerational effects pervade the novel.

But this is a tall history, with the emphasis firmly on the word tall. Ghosts and visions are commonplace, characters can communicate without speaking, fortune-tellers enter people’s dreams, a Chinese book takes away a girl’s ability to speak. There is nothing realistic about it, and yet Forbes makes the rural Jamaican setting feel so real and its people and mythology feel so familiar that it’s easy to suspend disbelief and go along with the high-wire act of an author weaving a deliberately tall story and somehow making it all hang together.

Alongside sugar and slavery, of course, Christianity also played a large part in Jamaican history, and the biblical resonances in A Tall History of Sugar are strong. Moshe is the Hebrew form of Moses, and like the biblical Moses, he is found as a newborn baby abandoned in a basket by water. Rachel, like the biblical Rachel, is unable to have children, so Moshe’s appearance seems like a miracle to her. And when she discovers the baby, she has a brief vision of a woman in a blue cambric dress trying to breast-feed the child – a scene that seems reminiscent of many painted scenes of the Virgin Mary with the baby Jesus, except for the detail that she “hoisted up her skirt to piss” at the same time. Moshe’s adopted father, a fisherman, also has a biblical name: Noah.

The novel explores issues of race through the unique character of Moshe, who doesn’t fit into any racial category: His skin is pale, his features African, he has one blue and one dark-brown eye, and his hair is straight blond in the front and “short, black, and pepper-grainy in back.” Although there are rumours that his father was a teacher and his mother a student at the school where “dreadful tings di white man-dem do to people young girlchilds,” this explanation does not fit the facts. Moshe is not mixed-race, a common enough category of its own in Jamaica. He is outside any categorisation at all. His sexuality, too, is ambiguous. The novel is essentially an exploration of how a boy who doesn’t fit in to any of our normal boxes gets through life.

At the centre of the book is a love story between two outsiders who, for different reasons, feel misunderstood by the world around them and take refuge in their own close relationship – so close that, from a young age, Moshe and his friend Arrienne are able to communicate without speaking. The book charts the decline of that relationship as the two grow older, losing the innocence of childhood and trying to understand the very different feelings of closeness and attraction in the adult world. Moshe’s attempts to discover the truth of his origins also drive them apart. At first, they go together to meet a mysterious old woman who communicates with Moshe through his dreams and reveals frustratingly little of what she knows about his real parents. But then Moshe begins to go alone, and eventually he travels to England in a desperate quest to knock on doors in Bristol and somehow find his long-lost father.

But even though Moshe and Arrienne lose their telepathic connection, they are still held together by fate, and they will continue to be drawn together even as the years pass and the book nears its conclusion. Although A Tall History of Sugar bears some hallmarks of a romance novel, it is not a romance. The author has called it a fairy tale, but that label doesn’t seem to fit any better than another possibility that she rejects: magical realism. In truth, it is a book that, like Moshe himself, resists classification. Despite the biblical allusions and the constant presence of sugar, there are no straightforward allegories or conclusions on offer here.

The story is told in a complex and deliberately inconsistent style. It is ostensibly narrated by an older Arrienne looking back on her childhood and frequently interjecting her own observations from the future into her stories of the past. And yet, for long sections, Arrienne either refers to herself in the third person or is replaced by another unspecified narrator. And, really, it’s Moshe’s story, told through Arrienne, thanks to their close connection. This is a story, it seems, that does not belong to anyone, that resists not just classification but also ownership, even by its own narrator.

The register also shifts wildly between formal English and Jamaican patois. In the early parts of the book, Forbes gives “translations” of the patois that are so stilted and formal that they seem designed to show the absurdity of the attempt: “‘Dat skin an dat hair gwine mek him way in dis world hard-hard. Hard travail. Mi si it. Ehn-hn.’ This unresolved body in which history has made ructions will make his pilgrimage difficult. This is what I have seen.”

These awkward “translations” mercifully start to tail off and, by the second half of the book, they’re gone altogether. We’re still left with the mix of registers, but there is no attempt to explain or translate. Some things, it seems, just sound better in patois, and the reader is trusted to be able to follow the code-switching.

The mixing works well, not just because it’s true to the cultural mixtures of the Caribbean but also because much of the language in both registers is beautiful. Two characters struggling to find the right words “approached speech sidewise like crabs.” The shadows of a sinking afternoon sun “had fallen like tongues on the hills.” A woman’s deformed feet are “like the image of feet held under water.”

There are frustrating moments in A Tall History of Sugar. It doesn’t set out to be a realistic novel, and its characters sometimes behave in ways that don’t make much sense. Moshe and Arrienne’s childhood friendship is beautifully depicted, but their later estrangement is less easy to understand. Moshe’s abrupt departure for England, without telling Arrienne and with only a slim hope of finding his father based on some sketchy information from a fortune-teller, is quite incomprehensible.

It feels sometimes as if the characters are being manipulated by the hands of fate: The fortune-teller foresaw that he would go across the seas, so he had to go. But in the world of a novel, fate and the author are hard to distinguish, and the hands of fate can feel like authorial manipulation.

It’s hard to be critical, though, of a lack of realism in a novel that doesn’t try to be realistic. It’s best to read it not so much for its plot as for its themes, its beautiful prose, and the way it brings the world of rural Jamaica to life so vividly and memorably. It’s a complex, thought-provoking, multilayered novel that, as you’d expect from a writer who’s also a professor of Caribbean Literature at Howard University, gives the reader plenty to work with, plenty to analyse, plenty to reread and reinterpret. It’s not always an easy read, but it’s a rewarding one.

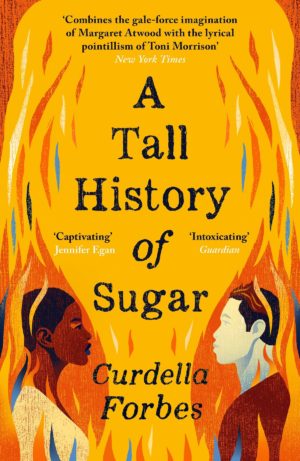

A Tall History of Sugar

By Curdella Forbes

Canongate, 366 pages

About Andrew Blackman

Andrew Blackman is an award-winning novelist who was born in London and currently lives in Serbia. He's written two novels, On the Holloway Road and A Virtual Love, as well as hundreds of articles, essays and short stories. He maintains a popular blog about writing and books, and spent five years travelling full-time around Europe with his wife, Genie, before the Covid-19 pandemic intervened.

- Web |

- More Posts(1)