You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

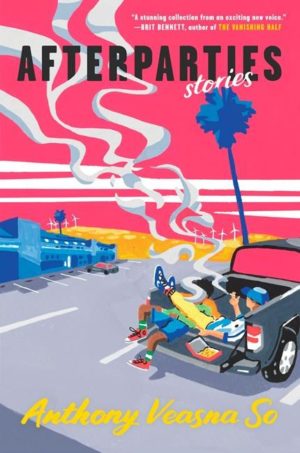

I was a third of the way through Afterparties when I heard that Anthony Veasna So had died, aged 28, eight months shy of its publication. It would have been his debut book, and he was poised, as the press put it, on the brink of literary stardom. I’m not entirely sure why I mention his death upfront. Partly it feels important to admit that I knew, because this knowing must have coloured my subsequent reading. This would probably have been a very different review if I’d assumed the author was still alive – more positive or negative I obviously can’t say, but different for sure. Another reason relates to a note in the acknowledgements: The author thanks a friend for being “an airtight vault of all my opinions that the world is not ready for yet.” It’s an intriguing line, landing just the wrong side of arrogant, maybe, but one which reframes the whole collection as an act of restraint. So, for as much as these stories will almost unavoidably be hailed as an authentic insight into what it means to be a queer, second-gen immigrant living in post-recession California, it’s worth considering that this is only what the author deemed palatable for our current (in)sensibilities. Wondering what those incendiary opinions were and knowing that we’ll never find out meant that much of my time rereading this book was spent looking for ghosts of them – imagining what these edges would have looked like before they were blunted. Finally, there’s something perversely fitting about So’s death being ever-present in my reading. So much in these stories is about how tragedy permeates everything (even – perhaps, especially – when we’re trying not to let it) that attempting to read the collection whilst ignoring the loss of the author felt inimical to the book itself. [1]

Afterparties is a collection of 10 stories, each one an intricate world unto itself. When placed together, they expand to the complexity of a universe. The niche is a Cambodian emigrant community living in California: the Mas, Bas, and Gongs who escaped the autogenocidal regime of the Khmer Rouge, and their half-American, half-Cambodian children. Anthony So was one of this new generation. Likewise for most of the narrators in the collection. Within this, though, So exhibits an impressive ability to convincingly voice a broad range of characters: male, female, gay, straight; and, in the final story, his own mother. The majority of the stories are also set in a similar period of recent history: the aftermath of the 2007–2009 Great Recession. Again, the specific locations are wide-ranging: a donut shop, the after-party of a Cambodian wedding, a down-at-heel old people’s home, a wat.

I was interested in Afterparties because I’d recently read Nothing Ever Dies: Vietnam and the Memory of War by Viet Thanh Nguyen. It’s a non-fiction book but opens with a line straight out of the next Great American Novel: “All wars are fought twice, the first time on the battlefield, the second time in memory.”[2] According to Nguyen, “cultural forms” (such as literature) have a role in memorialisation that can either prop up or undercut official narratives. I was intrigued to see what voices would speak through So’s book, especially after learning that Nguyen had read and praised the first story in the collection.[3] He described its success in an LA Times article, approving of the fact that whilst most Cambodian-American literature tended to focus on the terror and degradation of the genocide, So had managed to document the life and culture of Cambodian Americans living now, without forgetting that history.[4]

Focusing on a generation that didn’t experience the genocide serves to imbue its memory with ambivalence. In “Superking Son,” the title character is a badminton coach who also runs a failing convenience store. Superking Son vents about how he grew up “in the real hood,” training for badminton by curling boxes as he stacked shelves. The current generation will never understand his struggle, just like “the deadbeats (his) age will…never understand the Pol Pot crap.” But the young narrators reply internally that they do have their own struggles, because it’s “hard to do well in school, especially as a Cambo. And aren’t we supposed to aspire…to attend college and become pharmacists? Wasn’t that what our parents had been working for? Why our ancestors freaking died?” Each generation presumably wants the next to have it better, but they can’t help resenting this when it happens. Nothing gives Superking Son greater joy than finally taking Kevin (a privileged new recruit) down a peg, by beating him in one of the finest games of badminton the community has ever seen.

One generation’s chokehold on the next is made more explicit in the twin stories “Maly Maly Maly” and “Somaly Serey, Serey Somaly.” In “Maly, Maly, Maly,” the title character and her cousin Ves are “exiled” from Ma Eng’s house and the preparations going on inside: A sort of baby shower is being planned for Maly’s second cousin. The newborn has been heralded by Ma Eng as a reincarnation of Maly’s dead mother. So not only is the newest generation literally inhabited by the old, but the old deny the young the chance to decide which of the elderly they are inhabited by. Maly is rueful about the fact that her mother has been reborn to someone else – the second cousin – rather than Maly herself, and the reader feels the sense of unfairness in that twisted logic: If Maly’s mother had to die, if it’s possible that she can be reborn, then why couldn’t it have been Maly that gave birth to her? Instead, Maly is left worrying that the child she ends up having will be the reincarnation of Ma Eng, whom she hates. How this worry develops into resentment (again, the blame is misplaced), how intensely she ends up hating her second cousin, is seen later in “Somaly Serey, Serey Somaly.” The story is told from the perspective of Serey, the second cousin whose body Maly’s mother haunts. Here, the memory of the genocide generation is passed on with a little more agency, but one thing remains unavoidable: The ghost has to be passed on to someone. How they will then carry it is unknown.

The ambivalence towards the culture and history these characters (are expected to) carry is matched by their complex relationship with the culture they now find themselves in. Whilst risking the “if they don’t like it, they should go home” vitriol that’s often used to shut down any hint of “complaining,” those who contain more than one culture are often in a unique position to point out what the monocultured can’t see. The author doesn’t shy away from wry but on-point suggestions that the United States might not be so very different from Pol Pot’s murderous dictatorship. In “The Three Women of Chuck’s Donuts,” shop owner Sothy marvels that her hands, worn from working long hours making batter, have become those of her mother, who picked rice for the Khmer Rouge regime. Sothy’s kids have witnessed “drive-by gang shootings, the homeless men lying in the alley in heroin-induced comas, the robberies of neighbouring businesses, and even of Chuck’s Donuts once…” Most characters across the collection are struggling in the aftermath of the recession; most are workers in failed or failing businesses. The final story makes the brutalism more explicit, recounting a school shooting back in the 80s that left five kids dead (four of them Khmer) and thirty others wounded. But, despite the implicit and explicit disenchantment of capitalism in California, in “Safe Spaces,” narrator Anthony can’t stop cheating on Ben (his Cambodian lover) with Jake, an American guy he met at a Fourth of July party: “I reflected on the differences between Ben and Jake in bed, how Ben’s touch felt warm, never-ending, so different from the crashing rush I inevitably had, later that night, with Jake.” Similarly, back in “Maly Maly Maly,” when Ves finds a copy of Videodrome, he explains to his cousin that the film is a metaphor for being raped by the media. He muses that maybe this mind-fuckery is somehow necessary for survival, that “we had to let ourselves be violated by all those shows we loved as kids…Full House, Step by Step, Family Matters – Steve Urkel fucked us in the brains every day after school on ABC Family.” Throughout the collection, characters are fucked both metaphorically and literally by what they want and what they need.

I wanted to end by returning to that line about opinions for which the world isn’t ready. My guesses about these could be way off, thus proving the author’s point. It’s difficult not to guess, though. I keep coming back to another of Viet Thanh Nguyen’s observations: that “minority writers know they are most easily heard in America when they speak about the historical events that defined their populations.” This is what Western audiences are comfortable with, so it informs the realpolitik of the publishing world that minorities must navigate in order to be heard. We’ve already seen that Anthony So moved beyond this expectation, exploring the struggles and joys of first and second generation Cambodian-Americans, part-critiquing, part-embracing the American Dream. The reader grows more uncomfortable, because it’s no longer a harrowing book about “what those people experienced over there,” but an insight into “what these people experience over here.” Within the final third of the book, I felt a further shift towards how we ourselves experience the communities that So is writing about. I wonder if it’s here that we find a blunt knife or two that he was looking to sharpen later in his career. In the story about the school shooting, for example, the mother tells her son that, following the tragedy, Michael Jackson came to pay his respects to the young victims, thereby raising awareness. To which her young son replies, “but why didn’t he visit us sooner, so that people could notice us before?…Then no one would have messed with us. We would have been important.”

So what happens when we do finally notice? Do we, as in the story “Safe Spaces,”employ someone from that minority to “teach rich kids with fake Adderall prescriptions how to be ‘socially conscious’”’ through learning a syllabus called Human Development? And does this only apply “at the most elite of private high schools, the ones whose names started with a capitalised The and ended with a capitalised School, as if only the wealthy possessed a real capacity to ‘develop’”?

It is sad that Anthony Veasna So will not be able to share the opinions we need to hear. Maybe there are other authors out there, inspired by his example, already sharpening their knives. Maybe we should sharpen them ourselves.

[1] Actually, it’s more complicated than that. Certain characters in the stories arguably do try to box-off tragedy and, like squeezing a water-filled balloon, what’s inside is displaced, popping up elsewhere along their membrane. So it would have been possible, maybe, to write a review which “ignored” the author’s death, pushing it down until eventually something else bulged up and out of the review. This might have been a fruitful experiential way to engage with some of the themes in the book, but we’re around 500 words deep already, and all this meta-stuff is probably sapping your patience as much as it’s twisting my melon, so we’ll try and get to the actual stories now. Apologies.

[2] Fundamental to memorialisation is the name given to something, as well as who gets to bestow it. “The Vietnam War” (or “the American War” if you’re Vietnamese) wasn’t geographically limited to Vietnam; it included South Koreans, Laotians, and Cambodians. Memorialised differently, it expands temporally, too, becoming part of an endless imperialist crusade.

[3] Originally appearing in The New Yorker, it can be read here if you’re a paid-up subscriber/haven’t already rinsed your free views: “Three Women of Chuck’s Donuts,” by Anthony Veasna So | The New Yorker

[4] Emerging writer Anthony Veasna So died Dec. 8 at 28 – Los Angeles Times (latimes.com)

Afterparties

by Anthony Veasna So

272 pages, Grove Press UK

About Adam Ley-Lange

Adam Ley-Lange lives and writes in Edinburgh. He's currently trying to find an agent for his first novel, whilst working on his second. Adam is also an editor for Structo Magazine, which publishes short fiction, essays and poetry.