You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

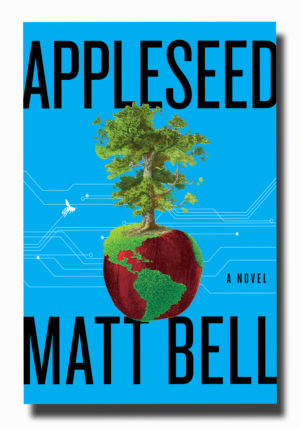

Johnny Appleseed had a dream to plant enough apple trees in America so that no one would ever go hungry. Matt Bell’s ambitious Appleseed takes that folk legend and grows it into an epic climate-apocalypse novel. With three distinct and interrelated narratives, the work is scattered with characters battling deep environmental and moral complexities.

In the 1700s, half-faun and half-human Chapman is planting apple orchards with his brother Nathaniel, who is driven by manifest destiny and financial opportunity. Centuries later we meet John, a surviving rebel in America, where climate breakdown has enabled EarthTrust to own vast swathes of land across the globe. For a humanoid named C-432, all that’s left of the American subcontinent is an ice sheet. Reaching a place named Black Mountain becomes his mission, without knowing why or who or what he will meet there.

Though Bell does a slow setup, building details of each world and their character’s mission over the distinct chapters, it is infinitely rewarding to stick with the novel. The book weighs heavy with symbolism, which works well to link the narratives. Chapman assists his brother planting trees, but his motivation is different from his brother’s fortune-seeking. All Chapman wants is to bite the apple from one tree that promises to free him from existing halfway between two worlds – animal and human. Chapman’s sense of selfhood is confused; outcast from the human world for being responsible for his mother’s death during his birth, he is not animal enough to live in the wild and not human enough to settle in a homestead. But when he encounters three witches – hags from a half-world – he can mutate magically from animal to human. But at what cost? Here history and myth are entwined not quite in harmony but in tolerable unity.

John’s life in the near future faces similar challenges, with the human population desperate after climate change has ravaged the lands, leaving the government held to ransom by EarthTrust’s advancing technological solutions. The language of place and survival becomes one of sacrifice, as choices are eroded as easily as the soil which once sustained life. We find John scavenging in the Western Sacrifice Zone, a place where nothing grows in the ruins of pipelines and human-made industrial decay. His once friend and ex-boss Eury Mirov runs EarthTrust and encourages climate refugees to relinquish their citizenship to work as volunteers on farming communities in exchange for food and a safe place to live. John has a mission to get to Eury and will do what he can to reach her. He might be circling the same routes trodden centuries earlier by Chapman, but the land is unrecognisable. As Bell writes, “One old myth of the West was that much of it was empty, barren, lifeless; a useful story, because one way to convince yourself to spread suburbs to the horizon was to tell yourself there was nothing there. It wasn’t true then, but almost is now.”

With nothing more than a song accompanying him across inhospitable ice, humanoid C433 has little use for language. He knows few names of animals and insects – to him language is factual, directional, programmed each time his software is updated. If he did come across an animal, he would not know how to name it. At one point he finds a list of extinct species. Without memory to grasp the scale of extinction, the humanoid has no emotional connection to loss. Bell’s work muses on such limits of language when everything is at risk. Nathaniel “speaks in the language of the settler, proud of stewarding the land, of improving the country.” Chapman struggles with his human side and the freedom animals have without language. Yet when he hears of the story of Johnny Appleseed, he is shocked by how the fable has become a lesser version of himself, each time moving further away from a recognisable truth.

Over the years of planting apple trees, the brothers’ disappointment grows, with Nathaniel realising the hard and futile graft of collecting dues for the apple orchards. Chapman, on the other hand, is disillusioned by irreversible change to the land, now tamed, farmed, and lost. He’s horrified and sees a parallel in the mutation of his body from animal to human form, “as if his hooves and fur were on the inside.”

Blame is considered universal under EarthTrust’s control; Eury believes “the problem belongs to every last person; until it’s solved everyone remains complicit, even if they resist.” Her politics may seem neoliberal, but Eury’s polished perfection hides sinister intentions: offering the world its last hope as she negotiates with the remaining political powers. John, having known Eury since childhood, is able to see her genius and her failings. But the tension is a moral one; what needs to be exploited to save the few?

The undercurrent running through Bell’s work is the swift erosion of democracy and government power. It owes much to contemporaries like Naomi Klein, whose analysis of the relationships between global powers and corporations is laid bare in This Changes Everything. That EarthTrust manages to take charge of America’s natural resources in under two decades is perhaps an idea not too far-fetched after all.

Conversations between John and Eury that take this standpoint are haunting. Eury’s desire to create a new world battles with John’s belief that she is selfishly driven to own the last living things of the world. Eury sources her ark-like collection of endangered animals, playing God with genome sequencing. John expresses horror at the sad face of the last Galapagos turtle trapped behind glass and the last grey furred wolf following without a mate. Bell vividly takes us to a place of poignant human blame, presenting the moral conflict of saving versus restoring. Both require sacrifice and complicity. Appleseed is not subtle in dealing with cause and effect; it is an ultra-modern meditation on what it means to be human and animal as the characters battle with what it means to save a world without a God: “Eury wanted to save the world too, but she never wanted to return to the Garden. Eury wanted to save the world only if she could also choose the future that came after, if she could be the one to decide what the human future should be.”

For a novel this vast in scope and ambition, Bell tries and succeeds in balancing storytelling with the posing of difficult questions about the morality of whose world it is to save, what is right and wrong. He certainly gives us much to consider as loss happens over and again, as things are rebuilt and changed, each time made new again. The characters’ names evolve and the use of names in the chapter titles shows the changes subtly, as when C-432 is rebooted as C-433, while giving a clear way of delineating the three timelines.

Bell weaves together real and speculative subjects with action-packed scenes and quandaries that will be sure to appeal to lovers of climate fiction. The landscape of opposing forces is a familiar one: the tension between human and animal, good and evil, hope and abandonment, myth and reality. Ultimately, it is a world almost too horrifically recognisable as our own, and we’re left with some powerful questions about our past and future: “Did you act while you could? This close to the end, you might not get to know if you did the right thing. A moment passes, a moment passes, a moment passes. In how many of these fleeting moments did you do nothing?”

Appleseed

By Matt Bell

Custom House, 480 pages

About Lindsay FORD

Lindsay Bennett Ford grew up landlocked in the North East of England. Her short fiction has been published by Ellipsis Zine, Bandit and Emerge Literary Journal. She is currently working on a novel.