You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

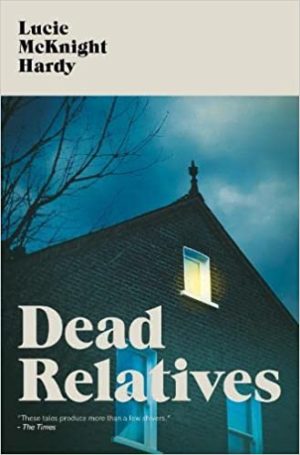

In her latest collection of short stories, Dead Relatives, Lucie McKnight Hardy takes us on a tour of the macabre. There are some strong themes running through these 13 tales. Many of them take place in a domestic setting, and there is a real sense of exploring the horror that takes place behind our closed doors. In some of the stories, this is particularly unsettling as we all want to be able to feel safe and untroubled in our own homes, but these stories push at those boundaries and unsettle us in some really subtle ways. The family dynamic is also a significant theme, and McKnight Hardy is really good at exploring unusual or dysfunctional family relationships.

My favourite story is the opening one, and the one that gives its name to the rest of the collection: “Dead Relatives.” Set in the 1960s, 13-year-old Iris lives in a remote, crumbling country house with her mammy, who runs a home for women dealing with unwanted or difficult pregnancies. Iris has no company of her own age – she has never even been out of the grounds of the house – and instead she finds company in books, her favourite toy (a gnarled old doll named Dolly), and the portraits of her dead relatives that line the landing walls. She often talks to the portraits, and sometimes they talk back, making her say things that she knows she shouldn’t. When three young women arrive just before Christmas, Iris bonds with one of them in a way she has never bonded with any of the young women before and she starts to confide in her, almost to the point of giving away the deepest, darkest of secrets and showing her Dolly, which she has been told she must never do. As readers we might think that it’s the eerie, chatty portraits that will provide some supernatural chills in this story, or the dead tree in the garden that Iris nourishes daily with a variety of different treats that she leaves in its hollow, but what actually comes to light toward the end of the story is far more shocking, and far more horrifying than anything ghostly could ever be, and the true horror here is what people can sometimes do to each other. I loved this story. It’s a superb piece of folk horror writing, reminiscent (as are others in the collection) of Shirley Jackson, and it’s the one that has stayed with me the most out of the collection. Being considerably longer than the others (it’s almost 70 pages), the characters and the setting feel so much more fleshed out and rounded, and you really do start to feel immersed in this insular, lonely world. I finished the story feeling there was still a lot more to know about Iris, her mammy, and the secrets they hold – and wanting to know it.

Another story that I really like is “The Birds of Nagasaki,” which is the tale that closes the collection. This is another tale of insular, lonely children, the jealousy and cruelty that can build between a brother and sister and again, like “Dead Relatives,” it features a hole underneath a tree that has a dark fascination for the children and houses some dark secrets. “The Birds of Nagasaki” is another story about terrible events that go unspoken but come back to haunt the protagonists, and it gave me chills when reading it.

There is a touch of dark humour to some of these stories, and sometimes the central characters get a shot at revenge or, at least, at some kind of satisfaction. “The Pickling Jar” and “Resting Bitch Face” are both good examples of this, with “Resting Bitch Face” being another particularly strong piece for me and containing some seriously tactile imagery that made my skin crawl.

There are so many things in life that are still unsayable, or only just starting to be said, and throughout this collection McKnight Hardy does an excellent job of exploring some of them. Motherhood and the maternal is a strong thread running through so many of these stories, and a number of times we meet mothers who are struggling in one way or another. In “Jutland,” for example, we meet Ana, who has just moved to a new home with her young family. Mother of two, a toddler and a young baby, she feels constrained by her maternal role and the fact that her husband’s career as an artist is flourishing while her career as a writer has stalled amid sleep deprivation, nighttime feeds, and dirty nappies. She craves the time and space to write and when she does eventually find it again, the words pour out of her, soaring and unstoppable. These words come at a terrible cost, though, and with imagery that will remind you of Susan Hill’s The Woman in Black, we are unsure at the end whether we have just witnessed a haunting or a mother suffering the horrendous agonies of postpartum psychosis.

In “Resting Bitch Face” the mother and son remain nameless and the child only referred to as “the boy.” Detached from her son, the mother admits to disliking him and is convinced that he dislikes her:

When the lesion across her abdomen became infected, she had thought of it as a sign of punishment – she was being called upon to pay penance for her dislike of the boy, and the pus that wept from the wound was there to remind her that she was a mother now, a putrid reminder of her new role. She thinks this is why the boy hates her.

There aren’t any missteps in this collection, and it is a great collection for anyone who likes to be unsettled or is a fan of macabre and folk horror. There is so much to unpack within these pages that they stand up to multiple rereadings, where there is often something new to be discovered.

Dead Relatives

By Lucie McKnight Hardy

Dead Ink Books, 224 pages

About Jane Wright

Jane Wright is a web editor, writer and photographer. Her short fiction has been published by Litro, Sirens Call Publications, Crooked Cat, Mother's Milk Books and Popshot Magazine. She lives and works in Manchester.