You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

Dear Victoria,

How many times have we started writing a letter, at pains to choose our words carefully, only to commit it to the wastepaper basket? Or simply not send it? Emily Dickinson wrote letters. Some people write songs, to provide the soundtrack of their life. You love Emily Dickinson. You chose letters.

As individual characters, letters together make words to tell our stories. More immediate, a letter becomes a personal conversation. These have not been written chronologically or in order of importance or preference. Whilst affirming for you, the collection is a talk with yourself, told through the being of other people.

Usually private, you expose your heart and emotions, leaving your ancestors’ lives wide open alongside the anonymous D, L, T, G, B, Y, that include the one that got away, keeping us guessing. They know who they are; they have coloured your existence. There is a reason for choosing them specifically, for they are the best recipients for your thoughts.

The use of “dear” strikes me too, although we don’t necessarily address people any other way. Here your every recipient, however close, is dear. Dear is sweet. It is also an appeal, in this case to memory. Not only the art of remembering, but also understanding, and retelling gratefully and sensitively. Dear also relates to a price to pay, and you mention intelligence coming at a high cost. The brain computes, creates, files, analyses and deletes. We cannot remember everything, but we can likely input the who, what, when, where, why, and how.

We meet you already as an accomplished poet. You find an artful way of “working over, through and under the conflicts,” as one teacher advised a younger you. Their ultimate gift to you was influencing your writing, striving for your better versions and expressions. It shows.One deemed your articulation “far from shy” – and these letters do speak loudly. As you deem reading “very spiritual,” so you reference the likes of Rilke, Oliver, Winterson, Chekhov, Stein, Glück, and Sontag in your writing. I would add Kephart, Lamott, Gornick to the reading list.

You kick your letters off with “so many questions.” Yes, there are a lot of questions, there always will be, even combined with answers. If Chekhov is to be believed, you need to formulate them (an art) in order to shape any answers, while Rilke urges us to “live” these questions. I wonder if in your philosophising you are questioning questions themselves. Any tension and discomfort we might feel in the questioning comes through seeking peace and resolution.

From a poignant opening line, the death of your mother – the foremost figure in your life – sparks this ferocity of emotion and desire to express yourself intelligently and in a visually pleasing manner… “Mother feels like an enormity” also shows the multidimensionality of grief, like an endless mind map. You admit to obsession, under which come death, loss, demise, existence – and this intelligence. We can identify our own triggers from a similar shock or disbelief, anger or depression. You throw in a touch of dark humour, charmed as you are by haunted poetry.

In your obits, you beautifully explain that “grief is wearing a dead person’s dress forever”and that “imagination is having to live in a dead person’s future.” You cannot speak for your ancestors, but only about the impact their life has brought on your life. And so you absorb a cumulative effect – the impact of your grandmother both on your mother and you, your mother on you, your own motherhood on your daughters, preserving the mother-daughter relationship within Dear Memory. I wonder if it might be a manual. Family is, was, will be our world and we don’t see beyond that sometimes. Except we do.

Moreover, I believe Dear Memory to be a continuation of your mini obituaries (obits) from “Obit.” You frantically wrote those in two weeks, “so you wouldn’t have to talk about it.” Your epistolary grieving is peppered with ironies and contrasts, within which we are exposed to matters of culture and tradition as well as ethnicity and identity. Exploring deeper, we ask how this can still happen today, at the mercy of immigration, adjustment to foreign soil, hoping that “what you acquire is better than what you have left behind.” As “there is pain in the past and pain in the present,” we continually seek out who we are and who we are becoming, where this pain intersects.

Your stories trigger recollections of my own and those of my parents and the generation before them. I can see exactly where the term “transgenerational trauma” is born:

“children of immigrant parents simply don’t have the experience or context with which to understand their parents’ trauma, so the trauma continues onto the next generation in a different form.”

Marianne Hirsch writes expansively, of “postmemory,” through circumstance and political misfortune. Fascinatingly described as “the relationship that the ‘generation after’ bears to the personal, collective and cultural trauma of those who came before,” it links to “experiences they ‘remember’ only by means of the stories, images and behaviours among which they grew up.”

We become part of a generation of postmemory, you and I. Trauma becomes common soil. Thus your stories and images deliver. It becomes obvious, the appeal of your memory book; there are communities the world over who are immigrant children, whose parents were victims of displacement, hardship and identity crises that too, consciously or not, pass down. Archives, scrapbooks from the mind spilling out onto paper. One thing for sure is that the past cannot be reversed.

And so where, then, does our present intersect with our parents’ past and present? Always our heritage, we can celebrate that past by being unique, as we have that extra something. It is the blood that flows through us that we cannot change. Are we not the sum of the parts, those pasts? Pride, recognition, and acceptance takes time and comes gently, and at a price, but it does. Because, as you say, we are human, and because for us, our lives are natural.

You shared a love for preserved salty plums with your mother; we might sense that food is your common denominator or ritual and makes you happy as you take us on a journey to discover this also. Two of the most powerful sensual memories to have are taste and smell, familiar in their deliciousness. In this way you paint your grief and loss through them. You describe your native Chinese food and the busy-ness of the restaurant your family owned, The Dragon Inn, your favourite bao-buns. Alongside bao-buns, your favourite tofu milk and braised tofu and pork.

Food is not, however, at the epicentre of your thirty epistles, although you do state that “food stapled your family to this country”when settling in America.Maybe you created a Dragon Inn memory box, containing napkins, chopsticks, menus, and business cards. Memories of my own mother’s dressmaking – such as her pins and inch tapes, needles, spools of thread, and scissors, are all kept in her original large wooden sewing box. But what I miss most is reading my parents’ handwriting – scrap sheets of calculus from my father’s engineering days, dockets from my mother’s dressmaking days.

If I were to write letters to them, I wonder what they’d sound like. Letters used to be handwritten and nowadays seem to be a lost art form but you resurrect them, in your loud, clear, hurting voice. You punctuate with humility and powerful metaphors, with a poetic, intelligent assault on the senses, including observations of nature in the form of birds and flight, wind and earth. You fondly recall certain objects as significant, such as cuddly toys, and teapots you gifted your mother from your travels.

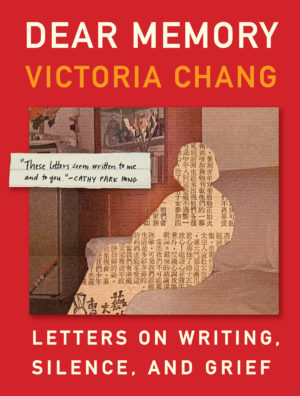

The old-fashioned photos contained within Dear Memory are rooted in identity. In parts substituted by cut-out captions, subtly or not-so-subtly altered with extracts, or Chinese script that ironically you cannot read or understand, it makes its mark. The pages are often separated by an all-telling red stamp – maybe for approval, something official, something branded Chinese. The colour red pops up between your book covers, also red, frequently; in recollected tales of blood, a Kit-Kat wrapper, pen marks in book margins when your father was learning English. The images become artworks themselves, providing important context for those past, present and future, echoing “how hard it is to speak up in the face of racism, to protect the self and the community.”

Equally, “The Marginalian” Maria Popova, herself an immigrant, observes: “We are born without choosing to, to parents we haven’t chosen, into bodies and borders we haven’t chosen…” and “we add experiences, impressions, memories, deepening knowledge ….” to which “it begins to feel not like a choice but like a constraint, an ill-fitting corset…”

In your own empowered tone, you speak your truth in universal themes and describe that you too aim to change history, encourage generational change – for it is up to us to keep it moving. As children we’re told how we came to exist against a historic or political backdrop. For your family it was the civil war in Taiwan; for mine it was WW2. At the time it passes over our heads as we are too young – our curiosity escalates only as we grow older – and “maybe our desire for the past grows after the decay of our present.” Then answers we need are harder to uncover, those that have them are no longer here and we are left piecing together what’s missing: certificates, souvenirs, mementos, all proof of an existence. Popova also refers to “people and ideas marginalised by culture, erased by the collective selective memory we call history…” where culture has “inherited parameters of permission and possibility…”

For all that, yours is a journey of recovery from trauma, steeped in authenticity and viewed from your present up and down the ancestral and generational line. Given you take on the trauma of a past, all would be proud of your collection. What would we say today if they stood before us?

These 160 pages read like a who’s who of faits accomplis. Seemingly written during the pandemic, you will have had time to dig, think, process, research, and soul-search. The letters are seen and heard in their outpouring of gratitude and loss, understanding and love… of things that were said and cannot be unsaid, or things that were not said at all and might be better left unsaid.

We learn such silence is common within your family. Silence from your mother’s glances, the silences when you asked her specific questions, through to her death, to the silence of your own “thinking stirring mind.” “You won’t know this but…” heartbreakingly introduces us to your father’s silence, unable to communicate, in a world of his own.

I wonder how many times the voice in your head stopped or propelled the letter-writing. Ironically, memoirist and writer Alison Wearing suggests that “limits can free us.” Your style of literary poetry and memoir have done that. What’s more, the knock-on effect of experience has provided continuity. As a result, there is “ample room to still love” after “all” is revealed.

I for one shall pay more attention to what lies beneath silences and look beyond what is in a photograph, image or letter. The silence – of what was not included in this collection, the silence of realisation and I believe resilience – how powerful it can be. When releasing the catch, you can let go, and make the past work for you in the present.

Aldous Huxley wrote: “after silence that which comes nearest to expressing the inexpressible is music.”

There’s more to come.

Dear Memory

By Victoria Chang

Milkweed Editions, 160 pages

About Barbara Wheatley

Barbara has a longstanding passion for language and the written word. A reader who writes, and a writer who reads, she freelanced her way in London for 8 years in PR, writing promotional campaigns, press releases, copy, slogans, etc., within the music and entertainment industry. She last promoted PR packages within the Press Association before full-time motherhood allowed Barbara to pursue her interest in Creative Writing. This creative enthusiasm led to 3 unfinished fiction novels. Now a mum to 3 teens, she has been a student on college and university courses as well as workshops and festivals, independently and online. A move to Devon saw her first flash fiction submission longlisted then shortlisted. Her work has regularly been published on Friday Flash Fiction (which also appears on Twitter) and has appeared on Paragraph Planet and several collections of new writing. In the pursuit of her true writing voice, she concentrates nowadays on Creative Non Fiction, where her experience and portfolio of work steers her organically towards memoir, essay-writing, journalism and reviews. On her writing to do list are more submissions and a blog; her TBR pile is ever-expanding. She is new to social media, but still into music, and a keen photographer, into pre-loved stuff and mental wellbeing, she is proud to have recently become a Litro contributor. Links to stories; http://www.paragraphplanet.com/jan1621.gif https://www.fridayflashfiction.com/longer-stories/birthday-days-by-barbara-wheatley https://www.fridayflashfiction.com/100-word-stories/hand-on-heart-by-barbara-wheatley https://www.fridayflashfiction.com/100-word-stories/on-the-horizon-by-barbara-wheatley https://www.fridayflashfiction.com/100-word-stories/clothesline-by-barbara-wheatley https://www.fridayflashfiction.com/100-word-stories/parking-meter-by-barbara-wheatley https://www.fridayflashfiction.com/100-word-stories/chocolate-box-by-barbara-wheatley https://www.fridayflashfiction.com/100-word-stories/way-to-go-by-barbara-wheatley https://www.fridayflashfiction.com/100-word-stories/potato-cakes-by-barbara-wheatley https://www.fridayflashfiction.com/100-word-stories/about-flash-fiction-by-barbara-wheatley https://www.fridayflashfiction.com/100-word-stories/gone-with-the-wind-by-barbara-wheatley https://www.fridayflashfiction.com/100-word-stories/case-study-body-parts-by-barbara-wheatley https://www.fridayflashfiction.com/100-word-stories/hope-by-barbara-wheatley http://www.paragraphplanet.com/jan1621.gif https://www.fridayflashfiction.com/100-word-stories/postcard-news-by-barbara-wheatley https://www.fridayflashfiction.com/longer-stories/come-home-by-barbara-wheatley https://www.fridayflashfiction.com/longer-stories/oh-potter-by-barbara-wheatley