You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

An individual radical Black male, according to bell hooks’ 2004 treatise on Black masculinity We Real Cool, named after the seminal Gwendolyn Brooks poem, is one who does not adhere to the social mores created by the imperialist white-supremacist capitalist patriarchy. Unfortunately, those social mores are often embraced and perpetuated (at times enthusiastically and at times unwittingly) by young Black males.

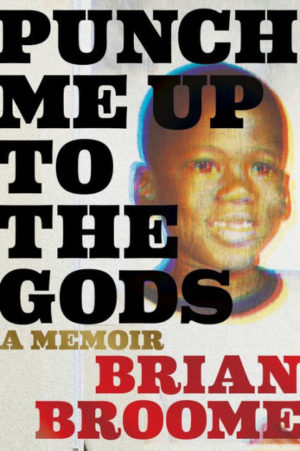

Flouting these social norms can be dangerous. Brian Broome’s memoir Punch Me Up to the Gods, which also takes a structural inspiration from Brooks’ poem, recounts his perilous rejection of a narrowly defined Black masculinity as well as his harrowing journey from Black boy to radical Black male.

Broome did not set out to be a radical Black male. At the time he grew up, in the place he grew up, this concept was something akin to a death sentence. What Broome desperately needed was to be “normal”; that is, straight, athletic, and most of all cool. Broome was not cool growing up. Coolness, that great gift bestowed on all Black men, or so the world would have him believe, eluded him. His older brother had it; he knew how to move, how to talk, how to lean against various objects with the right amount of nonchalance. These intangibles were out of young Broome’s grasp. He realised their import but he could not master them.

He paid dearly for his inability to do so. His father, his best friend, and other Black males terrorised him with fists and shoves and insults. They all wanted one thing: for him to be normal.

From the opening essay “Colder,” Broome describes the attempts to normalise him. It reads like Midwestern gothic horror, Sherwood Anderson by way of William Faulkner. As he and his best friend, an abusive 10-year-old named Corey, walk through the woods Broome sets the scene: “The sky was the color of concrete and the branches of the trees were stripped naked of their leaves and heavy with snow.” This is the colourless world to which he belongs and which is getting bleaker all the time. Corey is taking him to a farmhouse so that he can prove to an assorted band of his peers that he’s not white, which is to say he is not weak or effeminate or, God forbid, gay. This is the first of many tests that young Broome will fail.

Before long, it is clear to Broome that he cannot be converted to full Blackness. He will never achieve the necessary cool nor the necessary sexual orientation. Naturally, this leads him down the road of self-hate. He despises himself for liking boys, for being so dark, for being Black at all. He decides he’ll embrace whiteness. He’ll become respectable.

“Black boys are always a disruption in class and the Black girls are too loud and bossy, so I try not to be like them and blend into the background. But she doesn’t treat me any better.”

The “she” to whom Broome is referring is his sixth-grade teacher. She is white, and his attempts to distinguish himself from his peers do not endear him to her. His rejection of acceptable social norms is not prized for being radical but instead scorned for upsetting the natural order, for complicating matters. White people have expectations for his behaviour and deviations are unwelcome.

He knows this to be true, but the lesson does not stick. He learns it again when he uses dancing to win over white friends in high school or when he has sexual encounters with white men who fetishize his Blackness but care nothing for his person, especially because his person doesn’t conform to their concept of Black masculinity. Perhaps the book’s most audacious example of this latter phenomenon is the French professor who assumes Broome plays basketball but also empathises with Broome’s plight in the United States of having to live with “ze racism.”

Respectability doesn’t do Broome any favours in the Black LGBTQ community either. Once he escapes provincial Ohio for the comparative metropolis of Pittsburgh, he comes to find that his self-hatred bars him entry into the community that should rightfully be his.

He becomes unmoored. Broome belongs to no community, he has no home, no place to be himself, and no sense of that self. He was not the Black man that he was supposed to be and in failing to be that, he is nothing. Reading the memoir, one wonders how Broome was strong enough to go on living until one realises that his existence could barely be described as such. Alcohol and cocaine kept him insulated from reality and allowed him to put off dealing with his trauma. He went out night after night using bars to avoid being alone with himself: “I can’t take sitting at home on my own at night. Too many ghosts use silence as their time to attack.”

Every page of the memoir speaks to Broome’s vulnerability and courage. We see Broome at his worst, when the substances threaten to consume him, and he pulls back the curtain further still showing us his damaged roots, revealing his complicated relationships to his Blackness, sexual orientation, and gender. But the memoir wouldn’t work as a mere confessional. Even with Broome’s crisp prose and occasional levity (“Homosexuality, as it so often does, attacked me in my bed in the middle of the night.”), the book would be undone if it didn’t offer a modicum of hope.

As Broome narrates some of the seminal events in his life, he also recounts a bus ride, in media res, during which he observes a series of interactions between a young Black boy and his father. Broome uses the scenes with Tuan to jump into different periods of his own life, hoping against hope that Tuan will avoid the same pitfalls that he did not.

Make no mistake, Broome is not presupposing that things are going to be easier for Tuan. He has given up on the idea of an easier time or an easier place. Once upon a time he learned that Pittsburgh can be every bit as racist and homophobic as provincial Ohio. There is no escape. The United States and the world at large have been hostile to Black bodies. Gwendolyn Brooks knew this as does bell hooks as did Broome’s patron saint of Black literature, James Baldwin. There is no room for naivete. Broome, too, knows that Tuan and all Black boys have to be tough, but do they need to be so to the detriment of their humanity? After several decades, Broome has found that he doesn’t have to be. He can be a radical Black male, walking through the world as himself without self-hatred.

Punch Me Up to the Gods is a story of survival and perseverance. The title refers to a threat his father would make when Broome would step outside of the accepted parameters of Black masculinity. He would be punched up to the gods, up to the heavens, better to be dead than to be what he was. Broome did make it to the other side, he survived, but he did not find death there. Quite the opposite.

Punch Me Up to the Gods

By Brian Broome

272 pages. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

About Bobby Wilson

Bobby Wilson is a writer (and exciter) living in Nanjing, China... Retired from basketball but still a bucket... Hosts a bi-monthly podcast about Black literature ("The Most Dangerous Thing in America Podcast") https://tinyurl.com/yw5u26zr... Watches copious amounts of sportsball, westerns and detective stories... Got a novel just waiting to be published...

- Web |

- More Posts(2)