You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

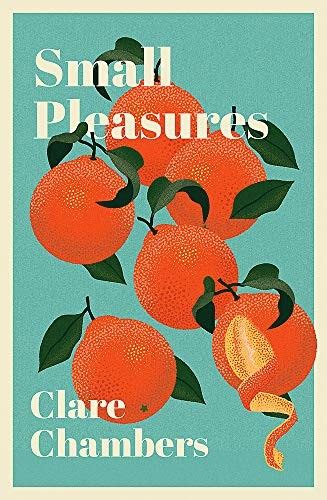

A word like parthenogenesis would usually send me to Google in search of a quick and easy definition, yet having read Clare Chambers’ new novel Small Pleasures, I feel rather nostalgic for a time when such easy answers were far harder to come by. For in taking this concept – which in layman’s terms means virgin birth – as its premise, the novel is essentially a detective story with a twist, a tale in which the mystery lies not in finding out who did the deed but in discovering whether or not the deed ever really happened at all.

Inspired by a real-life claim to immaculate conception, the book is set in the suburbs of postwar Britain and at times can feel rather quaint. Front gardens are carefully mowed, brass door knockers polished, the engines of cars as carefully oiled as gentlemen’s collars are starched. The central character is Jean, an unmarried journalist who works for the local paper. She lives at home in rather drab predictability with her elderly mother, taking pleasure in furtive moments of snatched irreverence: eating standing up, or smoking a cigarette spreadeagled on the sitting-room sofa. These pleasures are small not because of any lack in their intensity but because they occur in secret, when someone’s – in this case Jean’s mother’s – back is turned. Everything changes when Jean is assigned to the story of Gretchen Tilbury, a young dressmaker who claims to have conceived her now ten-year-old daughter entirely on her own. As Jean researches the story for the paper, she becomes increasingly embroiled with the Tilbury family, implicating herself inextricably in their lives. It soon becomes clear, however, that far more is at stake than simply proving or disproving the veracity of Gretchen’s claim, for as Gretchen herself observes, “everyone has a secret sorrow.”

Indeed, what really matters in this engrossing and extremely enjoyable book is all that is concealed – the secrets hidden behind those carefully polished front doors and neatly tended lawns. Indeed, with every stone that Jean’s investigation upturns, a new and uncomfortable truth is exposed. This play of concealment and revelation works well thanks to Chambers’ beautifully crafted representation of 1950s Britain, which demonstrates the very deep-rooted concern with appearance by which the era was marked. It is a concern that sees Jean shocked, for example, by Gretchen’s unconventional friend Martha, with her unkempt home and sink full of greasy dishes. More importantly, it is a concern that extends into a preoccupation with propriety and moral conduct that is often a source of considerable misery and frustration. This is typified when Gretchen’s daughter falls ill, leaving Jean to go alone with her husband Howard on a visit to his elderly Aunt. Jean is rather hesitant to go, fearing that Aunt Edie will disapprove of an unmarried woman travelling alone with somebody else’s husband. This reluctancy underscores the conservatism of society at that time and implies that the need to keep up appearances was very closely tied to an awareness of the judgement of others.

Chambers has said that the novel deals with notions of duty and self-sacrifice, and these are themes that depend on such a detailed evocation of postwar society. Jean cares devotedly for her housebound mother, working full-time whilst performing a whole range of now nearly extinct domestic tasks entirely on her own: “clearing out the larder,” “sewing worn sheets sides to middle,” and putting “elderly tea towels to soak in borax.” Her selflessness is exemplary to the point of frustration, the reader watching helplessly as each brief instant of happiness she is offered disappears almost before it has begun. As a model husband, Howard is similarly frustrating in his self-denial and respect for social mores. He admits to marrying Gretchen because “there was a certain amount of urgency” to provide her daughter with “a father and a respectable upbringing.” And as his feelings towards Jean deepen, he feels bound to honour his vows and avoid falling into the “shabby behaviour” of adultery, even when his wife quite openly chooses to abandon such standards herself.

Reading the novel today, one can’t help but wonder if our society is still as bound by moral imperatives of the type that Chambers describes. It is tempting to see the 21st century as the era of the “self,” in which the fulfilment of individual desires has become paramount, a world in which personal interest all too often takes precedence over any sense of duty towards others. The postwar setting is, therefore, the ideal place from which to critique our current state, teetering as society then was on the brink of quite massive change from which glimpses of the future could be briefly caught. Jean somehow intimates this while eating lunch at an Italian restaurant with Howard. “Everything about the meal was foreign and unsettling,” she reflects, her surprise at the lack of vegetables and the tiny cups of coffee, “suggesting that there were, just possibly, different ways of doing things.”

This excellently researched portrayal of the 1950s is rich with nostalgic charm and lends the work a very innocent, rather naïve feel, well-suited to a topic that relies so heavily on credulity to work at all. Yet despite its religious associations, what is important in Small Pleasures, is not the question of truth or faith but rather the very notion of mystery itself. It suggests that sometimes things are better simply taken as they are, that the contemporary obsession with definitive answers offers a narrow and rather limiting approach to the world. This is no doubt why I suddenly feel quite nostalgic for those pre-Google days, when some things remained secret and unknown and mealtime conversation didn’t end up in frantic reaching for a phone.

Small Pleasures

By Clare Chambers

368 pages. Orion Publishing

About Jane Downs

Having grown up in the south of England, Jane went on to study Arabic at university, travelling extensively in the Middle East and North Africa before putting down roots in Paris. Her work includes short stories, poetry, reportage and radio drama. Her audio drama "Battle Cries" was produced by the Wireless Theatre Company in 2013. Her short stories and articles have been published by Pen and Brush and Minerva Rising in the US. In August 2021 she joined the Litro team as Book Review Editor, commissioning reviews of fiction translated into English. Other works can be found on her website:https://scribblatorium.wordpress.com