You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

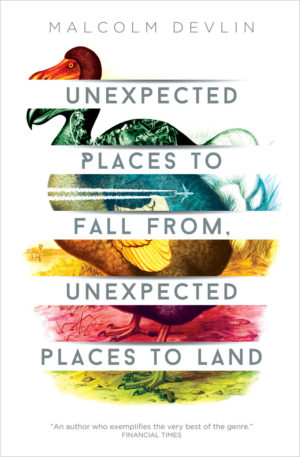

Unexpected Places to Fall From, Unexpected Places to Land is Malcolm Devlin’s second collection of short stories, after his genre-blurring debut You Will Grow Into Them. This new book follows up on Devlin’s ability to convey the uncanny textures of reality and the slipperiness of our sense of self.

In the first collection, the source for the uncanny was in scenarios dredged up from the same source as nightmares and legends. There were shapeshifters, metamorphoses, doppelgängers, an exorcist, and werewolves. In this book, however, the stories are more often than not rooted in domestic situations: a walking holiday, a delayed flight, long-ago summers on the beach, parents separating. The feeling of uncanny is more a way of seeing the world that permeates the stories. They are disparate enough that it wouldn’t do them justice to shoehorn them under one label, although the name Malcolm Devlin would have to be included in any list of best Weird Fiction writers.

Three or perhaps four of the stories take a recognisably sci-fi premise and riff on it. My favourite of these, “Five Conversations with my Daughter (Who Travels in Time),”fully lives up to the promise held in the title. “I have a secret. And you must promise not to tell anyone, not even me,” his small daughter tells him one night. It’s brilliant, and heart-pinching, and evokes a sense of how we are haunted by thoughts of what might have been, of the other selves we could have become.

This background sense of alternative selves and paths not taken is a hallmark of Devlin’s sensibility, both in the speculative stories and the thoroughly realistic ones. The second story, “The Purpose of the Dodo is to be Extinct” is in this sense an archetype of the collection (Devlin, by the way, is partial to long titles.) In this piece, Prentis O’Rourke dies in a car accident at a quarter past eight on the morning of October 16, 2019. The story exuberantly rings the changes on the many ways Prentis can die, all of them at that same point in time. “In a rare cosmic anomaly…Prentis O’Rourke died in every reality in which he had survived until his forty-second year.”

In one of the multiple realities, science has found a way to extract information about the alternative universes. His girlfriend/wife muses: “She tried to understand why so many of her had ended up with so many of him.” The names of characters in this story are reused in other stories in the book. Jack, for example, resurfaces with a different partner and job, but he is still the same reliable but rather clingy person. The stories, it seems, can be understood as being set in alternative strands of reality. But I don’t want to make too much of this – the collection is marked more by its diversity of genres than by unit.

“The New Man” is also worthy of mention as a sci-fi premise well executed. The narrator has had a near-fatal accident, and the dying flickers from his brain cells are scanned and transferred to a new brain in a new “basic model” body. There are large gaps in his memory and his feeling of selfhood. “Some of these straggly bits at the end might have to get left behind,” the doctor tells him.

Back at home he struggles to understand the changes in himself. This emotionally charged story taps into a primal strand of the uncanny: those moments when we fear we have become strangers to ourselves. The story feels like it’s an allegory of dementia, or perhaps the issues transgender people face.

Making up one third of the book, “Walking to Doggerland” is a virtuoso study of three aging sisters revisiting the holiday cottage of their childhood. There’s a calm assuredness that these characters are worth the time the reader will spend with them. Even the micro-drama where Penny insists on visiting their older sister alone, without Veronica, is gripping. The writing is beautiful and precise without ever trying too hard. Here is Lulu on their final childhood visit to the beach: “She snatched up her cardigan from where she had left it in the grass and set off towards the cliff path, her movements wiry and careless, her face cast up, her eyes closed, accepting the grace of the afternoon sun.”

This novella-length story is divided into three parts interspersed with the other stories. I enjoyed it so much it seems churlish to object that it doesn’t quite fit in with the “weirdness” of the remaining stories, or that it seems to be crying out for a larger canvas. (Dostoyevsky lingered more than a thousand pages with his three brothers.) One sister followed the religious life, one the artistic, and one became a homemaker. It’s a classic slow-burning character study, 19th century in scope, reminiscent of such writers as L.P. Hartley.

Another story in the realist mode, “My Uncle Eff” is a paean to those self-mythologizing eccentric uncles we all know, whose incomprehensible stories are only understood years later. They occupy that liminal space of being adult-figures but with visiting rights to the child’s world. “My parents told Eff they thought I was too young to hear the things he had to say.” Real-life bachelor uncles tend to diminish in legendary status as we grow to adulthood; with Eff, however, his story becomes truer and stronger. Any weirdness in this story is solely in Uncle Eff himself. We are left with the sense of childhood awe that there are people like Eff.

Nine excellent stories here along with the novella, and each one has a core premise that makes you want to grab someone’s ear to tell them about it. “Talking to Strangers on Planes”uses a reversed time sequence, so the first scene is the last chronologically. The slight distancing effect is strangely effective, perhaps psychologically corresponding to the way we get to know some people in brief encounters.

“We Can Walk it off Come the Morning,” a folk horror story set on a holiday in Kerry, did not feel as effective as the others. There is nothing in the characters’ lives, not even a spiritual or emotional emptiness, that might lend energy to the story and justify the eeriness invoked.

Some writers use the weird to explore the discombobulation peculiar to our era: digitally-deluged, politically-fractured, accelerating into the future. But Devlin’s concerns are usually classic humanistic ones. Growing up, realising our parents are human, making the decisions that will determine who we become, the myths we make for ourselves and our children, the different ways we make sense of the world. “It’s like we’re operating in two different versions of the same world,” Aleyna remarks about her boyfriend’s divergent understanding of their relationship. Precisely. And Devlin will selectively draw on weird or realist techniques to explore this.

There are lots of interesting things happening in the British short story, with writers like Adam Marek, Gary Budden, Sarah Hall, Angela Readman, Daisy Johnson, and many others making free use of fantastical or weird elements. The short story is a natural home for forays into the weird – after all, if the weird is sufficiently delineated, it ceases to be weird and becomes a world with a different set of rules.

The heterogeneous nature of the collection will not please everyone: Those readers who appreciate the novella-length unfolding of the three aging sisters’ lives may differ from those who prefer the intense puzzle story “The Knowledge” (A tribe of ratman cab drivers in London?) But in every mode Devlin proves a maestro at conveying the elusive dialectic of belonging and estrangement.

The pitch-perfect cover has to be mentioned: the classic George Edward’s picture of a dodo, sliced up and retextured so it’s not clear if the sections fit together. The dodo is at once exotic and faintly ludicrous. The image evokes extinction, the Age of Reason, the limits of science, and how our view of the world is assembled from disparate parts.

Unexpected Places to Fall From, Unexpected Places to Land

By Malcolm Devlin

Unsung Stories, 352 pages

About Aiden O'Reilly

I am originally from Dublin, and graduated in mathematics. I abandoned a PhD in complex dynamical systems. Later I lived 9 years abroad, in London, then Berlin, and later in Poland. I have worked at many different jobs to earn money. My short fiction has appeared in Prairie Schooner, the Dublin Review, the Stinging Fly, the Irish Times, and many anthologies and literary magazines – a total of 29 stories. I review books for the Irish Times, the Dublin Review of Books and other places.