You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shoppingAt the end of last winter I caught a cheap flight to Tel Aviv, met up with a friend, and we made our way to the Holy City on a local bus. We’d spent a mesmerising night in Jaffa, the Muslim quarter, woken by the call to prayer, and brushing by young Israeli hipsters in the market area where we ate overpriced food. We planned to cross into Jordan in the south of Israel by bus, then travel into the desert. But more on that later. On our very unglamorous hikes between train and bus stations we had our first glimpses of the B side of Israel – gritty neighbourhoods, concrete eyesores, Ethiopian dress shops and foreign workers traipsing by. We missed upmarket Tel Aviv and moved on.

From crusaders to missile fire over the Garden of Gethsemane

As the bus carves through Jerusalem’s sparse surrounds to the wind-swept, rock-bound city, I try to remember biblical references from girlhood Mass attendance and my love of art history. Jesus Christ. Calvary. The Mount of Olives. The Garden of Gethsemane. Then Caravaggio, Mantegna, Fra Angelico. I hadn’t really intended to visit Jerusalem, being unsure what to wish for and expect, but it was on the roadmap we had drawn up on our way to nearby Petra and Amman, places I had yearned to visit for years. Already the off-duty kid soldiers at the bus station, machine guns slung in laps, made me uneasy, as I recalled border skirmishes, Palestinian youths shot, bulldozers, missiles. We hop off our bus and ask street directions from a gentleman in Hasidic dress. In my ignorance I had assumed traditional clothing might be reserved for special occasions, but I was soon to see that this aspect of life in Jerusalem – the dapper tights, shoes and shiny black skirt, the hair curls and extravagant hats – is a vital omnipresent feature.

Air Bnb has a stranglehold on the world of el cheapo tourism on every continent. We book ahead as we move – our lodgings include a Bedouin tent in Jordan’s Wadi Rum national park and I receive a WhatsApp vocal message from our host Tariq Ali, spoken while desert winds blow in the background. In Jerusalem, we enter a couple’s apartment – their existence, it seems – complete with selfies taken in Washington, weird soft toys, broken hair dryer. Life in the contested territories might be cheap, but for a young childless couple in Jerusalem, the cost of living is high. Extra shekels from tourists help. By the end of our days there, we are wondering whether R (guy) will one day be wearing Hasidic garb, and modern C (girl) is destined to wear headscarf, drab skirt and flat shoes, leading a batch of children, the little boys with shaven heads and corkscrew curls. The Chosen People – is what I frequently feel as I see these family units pass us on the streets.

Up and over the hill through the heaving Mahane Yehuda market, we cross the modern centre and join tourists of all nationalities funnelling through the alleyways of the walled city. Our first visit is by night and there is a chill off the ancient stone. With little forewarning we find ourselves in the floodlit open-air arena before the Western Wall in the Jewish Quarter, watching nodding worshippers from afar. The flagstones descend in a mild slope to the grass-tufted stones of the wall. There is a continual arrival of men to pray. And of women to a sectioned-off stretch of wall to the right. Used to the emptiness of churches in Italy where I live, I watch the way worshippers stride towards the undeniably holy energy of the site. I remember photos in my father’s Time magazine of the Western Wall. I remember the Camp David talks and the Six Day War; the decades of blockades, missiles and slaughter. Good guys versus bad guys. Headline fatigue. Munich, Sadat, Begin, Arafat. Now I am standing before this timelessly powerful monument, breathing the cold air in awe, remembering the House of David and the crusades, thinking that this is the source, this is what it was all about.

King Herod, errant observer of Judaism and vicious despot who executed his beloved wife Mariamne I and three of his sons, was a client ruler of the province of Judea under the Roman empire. Herod was responsible for the construction of the Second Temple, built upon the four sustaining walls around the Temple Mount. The Western Wall is the last remaining wall from this grand structure destroyed by the Romans in 70CE. Today’s Temple Mount is the site of the Islamic shrine of the Dome of the Rock, whose golden cupola rises above the labyrinthine Old City with its four religious zones existing shoulder to shoulder – the Jewish, Muslim, Christian and Armenian quarters. First constructed under the Umayyad Caliphate in 691–2CE, the Dome of the Rock is built over the Foundation Stone central to Judaic and Islamic beliefs. It is both where Abraham attempted to sacrifice his son, and where the Prophet ascended into heaven. Maddeningly, we are unable to enter the Holy Mosque, having missed the afternoon when non-Muslims are allowed to visit the grounds, so we opt for over-sweetened tea while watching visitors.

A brief, winding hike away stands the equally significant bastion of Christianity, the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. This fourth-century cluster of sombre domes is built over Calvary, supposedly the site of Christ’s crucifixion, and bears his hallowed tomb, guarded by a brusque Greek Orthodox priest, given the property is governed by the Roman Catholic, Greek Orthodox and Armenian Apostolic churches. The religious determination of milling tourists gets under my skin – there are women wiping the tombstone with cloths, or laying hands there to absorb the distilled energy of centuries. I find myself placing a hand on the ancient rock, thinking of the many souls who have passed through here before me beneath the same redolent light.

When I was in my twenties I drove a tiny Renault around Cathar and Templar country in the south of France, sleeping in the back seat and sunbathing in fields with French cows. My fascination with the crusades took me to Albi, Carcassonne, Rocamadour; my love of architecture and art history took me into every cathedral rising on the horizon, where I pored over Black Virgins and Romanesque capitals and barrel vaults. I’d fallen for Ancient Greek history in high school and followed that up in university with a course in religious conversion movements and the missionary-speared economic expansion of capitalist Europe in Africa. Walking through the religious sectors in Jerusalem makes these intersecting interests tumble into place. On our last afternoon we take the Via Dolorosa towards the Mount of Olives, a ridge east of the Old City which has been a Jewish cemetery since antiquity, also where it is said Christ ascended into heaven. We look back to the burnished cupola of the Dome of the Rock. The overlapping of history and religion is astonishing. We stare at the much-contested capital, plundered and suppressed countless times, which has seen a succession of Jewish, Greek, Roman, Byzantine, Christian, Persian, Arab, Turkish, British and now Israeli leaders, including the ever-meddling Trump clan. In 2007, the city celebrated 3,000 years of existence from its establishment by King David.

I wonder if there has ever been a sleepy period of peace along these stony valleys. As we return towards the Garden of Gethsemane where Judas delivered his treacherous kiss, we recall Monty Python’s Life of Brian – Brian in his nappy on the Cross and John Cleese as a Roman centurion. We halt when we see smoke rising from the nearby Palestinian territories of the West Bank, followed by an outbreak of gunfire and crackling. We follow the whine of sirens crossing beneath the glistening afternoon cityscape.

Desert fire, desert wind

We take a night bus out of Jerusalem towards the border resort of Eilat. Date palms, roundabouts; more kids with machine guns and boots. At 6.25am we wait for our documents to be checked on the Israeli side, and then march through to Jordan to wait for our passports to be stamped. We had decided to take the Aqaba crossing, visiting the Wadi Rum national park before heading north to Petra, before ending our trip in Amman. A friendly border official shares an orange with us. His cranky colleague fires up his computer under a broken ceiling panel with cables dangling above our heads. The border has been sketched out along the gap between two arid mountain ranges pressed to the north-eastern corner of the Red Sea. A few hours later Aqaba is behind us. From afar, its minarets and handsome, crooked hotels face the equally handsome crooked hotels of Eilat on the Israeli side, both resorts offering diving trips, seafood fare and middle-eastern delicacies. We drive north into the desert on a broad road in a crazy taxi.

There is a turn off the dusty highway towards a valley of monoliths. This is where we are headed for the next few days, where we are soon to meet Tariq Ali, who will transport us to his alluring Bedouin camp. On the screen, we saw a brief row of individual tents under a rockface, each one decked out in remarkable fabric. It seemed too idyllic to be true and, though neither of us has voiced it, I think we are both fairly sure we will bum out on this one. We are picked up by Tariq’s “brother”, told to hoist ourselves into the truck and the vehicle jolts through a dusty bessa-block village before the bumping ride over red sand begins.

It is not yet sunset. The sky is at her most appealing, rose and resonant orange bordering a saturated blue. We fly through a wide valley walled by glorious rock formations that run to around 150m high. The valley is immense. Occasionally, skirting these sculpted rocks, we see a half-dozen tents in formation. Evidence of tourists like us. The sand is grooved by tyre tracks with tiny flowers surging on mounds; camels idle across the sand or are led by robed men on foot. The hugeness is hard to describe. The panorama becomes more dramatic, more extensive, more impossible to comprehend with mere vision, or the cameras and iPhones we abandon in order to invite our senses to expand. The odours of the desert; the texture of wind; the disarming quiet when the engine stills.

Our tent is a peaked, fabric-lined box, raised off the ground. A steel-framed opening on a jamb provides an overwhelming view of the reaches of the reddened valley. We are thrilled as kids. Across the valley we see a faded wall of rock which we decide immediately we will march to on foot.

Communal meals take place took place in a long, tapestried tent with lounges surrounding an evening fire. Window openings overlook the smouldering panorama as the cold mounts. The cook prepares chicken and vegetables in an ashen-covered hole in the ground. Guests are scant and quiet; our hosts ironic and teasing – used to a steady stream of tourists. Though we venture out on a jeep ride to vantage points along the valley the following day, the most startling moments are when we pace out into the immensity of the desert ourselves: in one instance a startling canyon with bleeding russet rock faces; on another afternoon we climb the first pinnacles of the stony walls above our campsite. Up here we sit in the rustling desert silence, watching the miniscule traffic threading along the valley paths below, or the stationary rock masses that have observed the fleeting lives of humans. I could have stayed there a week absorbing the unexpected birdsong, the smell of the earth, the sensation of light, the cooling winds over the implacable mountains.

The wounded valley – a walk through Petra

We travel on to Petra by bus where we’ve booked a cheap hotel in the town above the widely visited rock settlement. Our room is between the main mosque and a startling pastry shop run solely by men, where we ogle circular trays of golden syrupy Jordanian sweets, taking home a batch for breakfast. We head downhill in the morning to the entrance to Petra, where we present our Jordan Passes (bought online before we left, allowing travellers entry to many archaeological sites and the chance to waive the visa fee) and join tourists heading inside. Sculpted out of red sandstone by the Nabatean people and originally known as Raqmu, at its peak in the first-century CE Petra was a vital trading city inhabited by 20,000 people. Originally nomadic Arabs, the Nabatean people became sophisticated builders who harnessed erratic desert water supplies in order to establish the naturally fortified settlement. A client state of Rome, and eventually a part of the empire, Petra dwindled in significance after an earthquake in 363CE and faded from prominence, being revealed to Western eyes by the Swiss explorer Johann Ludwig Burckhardt in 1812, who gained entry to the site disguised as a Muslim.

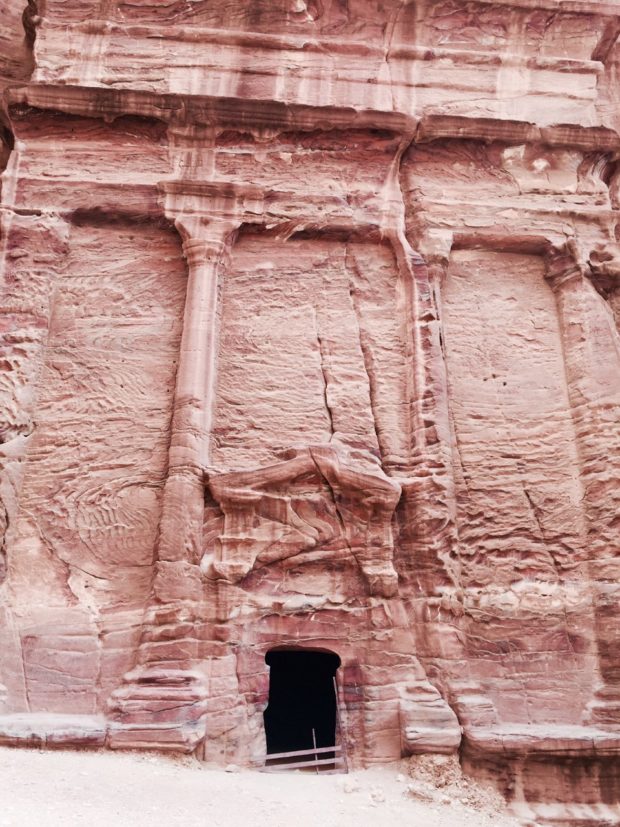

Today’s Petra is a UNESCO site, keystone of Jordan’s thriving tourist industry. Visitors enter via the 3–4 km long Siq, a natural passage between sandstone walls leading to the wider valley where the spectacular main buildings are carved out of marbled rose rock. Along the Siq we dodge locals charging through on festooned horse-and-carts transporting elderly tourists, and I recall my aversion to Venice and Rome in the summertime, fearing this will be a similar tourist trap. The narrow gorge opens onto the astounding façade of Al Khazneh, the Treasury building, its two tiers of columns and decorated architrave extending to the cliff edge above, remarkably preserved. The distinct Nabatean style emerges from this alcove excavated from the vertical rock, with shallow caverns looming behind the acanthus-topped columns. The cool earthen smell and the abandoned quiet of the ancient façade contrast with the melee of tourists below speaking all languages – the Bedouin guides with their oiled black locks and kohled eyes who make Johnny Depp look like a fraudulent copycat, camels in colourful saddle gear like gawky young women.

Snaking through the valley is a wider road that widens before a carved reddish amphitheatre. Rather than the incense traders of yore, today’s arena is busy with souvenir sellers and young men walloping ponies; a wry boy who looks part old man offers a ride on his Ferrari-4×4 donkey. The theatre looks towards a series of dramatic façades chiselled into the stone, identified as royal tombs. At the end of the day these grow golden in the light and we climb to the chambers within, long-ago emptied prisms awash with textured rock planes. From this humbling vantage point you turn back towards the gilded spread of the hidden valley – the half-ruined Roman road and a Byzantine church atop a hill, the massive sandstone block foundations of the great temple smashed by the long-ago earthquake, and the well-worn trail leading up to the serene monastery of El Deir.

We drink fresh pomegranate juice, buy cheap scarves from women who pretend to compete with their sisters ahead. There is a sense of not-yet-unruly mass tourism – I hear an elderly Australian couple, the guy struggling with a walking stick, and wonder how they have come so far. By the end of the day the winding path reeks of horseshit, the tourists have set off uphill to their hotels and the dying light catches exquisite detail in the diorama before us – the manmade enhanced by centuries of desert wind. The invisible Nabateans return as ghosts and gods.

Amman – the welcoming arms of a well-fed city

On our first morning in Amman we read of the Christchurch massacre on the other side of the world, ahead of time. Muslims at prayer in the suburbs. Families. Kids. It is a revolting outrage, made more obscene by the fact that we are travelling in a peaceful and welcoming Muslim country, where the pre-dawn muezzin has been a soothing balm through our slumber.

We catch a bus out of town to the ancient Roman settlement of Jerash, with its pitch-perfect theatre and stunning oval piazza, and the 60-ton stone Corinthian columns of the destroyed Temple of Artemis standing amidst flowery grass. We walk under Hadrian’s arch, erected when the Roman Emperor visited his dominions in the winter of 129–130CE, with his entourage and preferred Bithynian lover Antinous, who would soon drown in the Nile and be deified after death.

Back in Amman we set out downhill to the centre of this crammed, elegant city draped across a ring of hills, also settled by waves of conquerors from the Persians to the Ottomans. Since 1921 Jordan has been ruled by the Hashemite family, who claim descent from Muhammed’s daughter Fatimah. We pass the central mosque in the midst of a vast souk where we buy tea and incense; I admire the red and black traditional dresses adorning ranks of plastic models – though there are no slim sizes for me. In shops and falafel bars we see photos of King Abdullah II and Queen Rania enjoying local food haunts. It feels as though there is love and closeness in the community. We eat unforgettable falafel sandwiches at Al Quds Falafel, and an unbelievable meal at the downtown Hashem Restaurant. We join a queue to the city’s top sweets bar – Habibah – that specialises in kunufeh, a semolina dough soaked in syrup and rose water with a layer of cheese beneath, sprinkled with pistachio nuts on top. Amazing! We join a row of beatific faces eating from plastic plates in a side street. Above us, there is another hill to climb towards the ruins of the Roman Temple of Hercules – visited on this sparkling afternoon by locals and tourists alike – for the lavish view of the many-faceted buildings covering the surrounding hills, including the crisp arc of the second-century Roman theatre still in use.

The call to prayer rings out, and we are coming to the end of this rich voyage. The afternoon sun lowers, cutting over the city, highlighting the ridge miles away that we will have to climb to get back to our cheap hotel. Several things I have learned on this brief Middle Eastern jaunt: an Italian passport opens more doors than an Australian one; the desert is a place I would like to return to; I thought I knew how to make hummus but I was clueless.

About Catherine McNamara

Catherine McNamara grew up in Sydney and went to Paris to study French. She ended up in West Africa running a bar. Her short story collection 'The Cartography of Others' is finalist in the People's Book Prize and won the Eyelands International Fiction Prize. Her flash fiction collection 'Love Stories for Hectic People' is out in May. Catherine lives in Italy and has great collections of West African sculpture and Italian heels.

- Web |

- More Posts(13)