You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

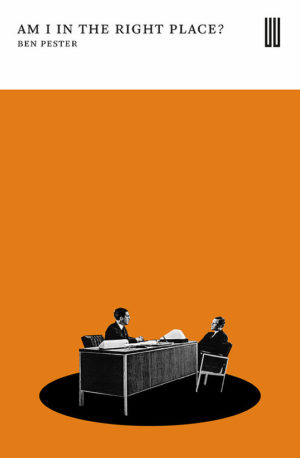

“He is toying with us.” So say the narrators in the penultimate story in Ben Pester’s debut collection Am I In The Right Place? It’s an apt summary of the ambience of the whole. In response to the madness of being human in this world, Pester has spun dreamlike tales that sometimes begin as ordinary and that other times are narrated by, say, an underachieving block of wood mothered by a human woman. He’s toying with us, and we know that he is, and it’s great fun.

These stories are run through with a combination of sadness at home and frustrations at the office. Pester’s bio says that he is a technical writer in the tech industry – a turn of phrase that sounds much like one of his characters’ all-too-relatable office experiences. Take Theo in “Rachel reaches out.” He’d “been given a lot more responsibility since the shake-up in May, and now everyone in the whole of SME/APU wanted a piece of his ass.” We don’t know anything about the shake-up or the meaning of that string of abbreviations because the meaning doesn’t matter, and that’s exactly the point. While “Rachel reaches out” teases the inanity of interoffice email – “she hit send and sighed as the email-whoosh came through her headphones. Theo was sitting at his desk less than six metres away…” – “Low energy meeting” takes us through a meeting held during an apocalyptic event, led by a line manager who pushes a single shared box of Maltesers on his staff like a besotted grandmother. The meeting concludes as the line manager requests four volunteers to help him feed a being – the physical manifestation of unrequited childhood love – back into his mouth: “We must hope that he will soften, yes. Much depends on him softening or all will be lost.”

But the collection eases into the weird. In the first story, “Orientation,” an overzealous health and safety officer feels only slightly exaggerated – and entirely hilarious. Boldly told in the second-person, the story guides “you” around the office, forces “you” to mime safe use of the taps, warns “you” of the dangers of using the microwave, and directs “you” where to find stationery (within a cupboard that is also a portal to childhood trauma, of course). And in the title story, a man and father desperate to connect first manage a delicate lunch before embarking on an ethereal journey toward the past and a chance to right the wrongs in their relationship.

Cupboards, holes, cracks – all are recurrent images in this collection, typically death traps hastily covered over or ignored. But in “Lifelong learning,” a cupboard holds a means of escape: “It was obvious that you should not climb into this cupboard, but you climbed into it anyway. You pushed your way to the back of the cupboard, which was enormous and filled with a strange mist…You sat in the phenomenally cavelike back of the cupboard and read all about the reasons and ways people were welcomed to the village.” The story takes us on a journey to the village, along a long, dark road full of with mysterious figures that are sometimes embodied childhood memories.

These cupboards and crevasses feel distinctly Beckettian. As Hunter Dukes explains in his essay, Beckett’s Vessels and the Animation of Containers, Beckett “often explore[s] the gray area between the human and the nonhuman: objects that are almost human, humans that are almost objects…where this type of thinking is present, we also find a vessel of some kind.” Indeed, Pester’s stories are riddled with near-humans, such as Tritty, the egg/colleague/spiritual advisor that turns malicious, the cats in “Sheba” who punish those whose behaviour is too human-like, and, of course, the wood object in “Mother’s Day card from a Wooden Object.” Even the frightening cracks – the ones that are clearly portals to death, such as in “Sheba” and “How they loved him” – are mostly accepted as the necessary path forward, dismissed as a fact of life: “But, as you can see, that thing, that gaping hole is back again!…We were going to call the council, but they won’t come…I mean, what are we meant to do about that?”

These surreal stories are not without their heartbreak, mostly due to families torn apart by literally impossible circumstances. A man reduced to wadding for a colleague’s wound idly acknowledges that his family is unperturbed: “My children say they do not miss me too badly.” Sheba the cat watches as her human family’s bodies are stretched into a hole: “Sheba remembered the mother. It was actually really very interesting to watch her trying to grip the floor, the varnished oak floor, with her face. With her nose, ramming it, trying to get a purchase as teeth buckled. Gurgling because her arms were useless spaghetti. The baby had gurgled too, when it had gone in, eventually.”

Pester’s stories marry the ludicrous and the profound. We see death and pain as inevitabilities but also beauty in moments of introspection, patience, and understanding. Pester breathes life into inanimate objects and the inhuman, making us believe that they feel and that others feel for them, too. These absurd stories – while very much unlike real life – feel intensely familiar.

Am I in the Right Place?

By Ben Pester

194 pages. Boiler House Press

About Monica Cardenas

Monica Cardenas is a writer living in the U.K. She holds a PhD in Creative Writing from Royal Holloway, University of London. Originally from Washington, D.C., she earned a BA in English from Wilkes University, Pennsylvania. Her novel-in-progress The Mother Law was longlisted for the Lucy Cavendish College Fiction Prize and runner-up in the Borough Press open submission competition. Her writing appears in Litro, Sad Girls Club Lit, and Catatonic Daughters.

- Web |

- More Posts(4)