You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

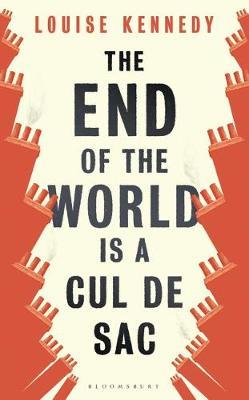

The bittersweet beauty of this book is perfectly captured by its wry title. Indeed, in this debut collection of short stories by Irish author Louise Kennedy, dramatic events are met with weary resignation, life’s pains and sorrows experienced as things so predictable and familiar that they are almost cherished. The book reads in many ways like a panorama of personal intimacies, as if the author’s lens is panning around the smooth curve of the cul de sac, relating the myriad of individual stories that take place behind each quite unremarkable façade.

In the story from which the collection takes its name, the main character has been abandoned by a husband whose dodgy deals have left her the owner of a decrepit housing estate, a poor reputation as a “gangster’s moll,” and a large, fancy house that feels so much like a show-home that she prefers to sleep in the boot room than in any of its spacious bedrooms. When a donkey strays into the estate, she meets a young man who presents a new and unexpected ray of light on an otherwise rather grim horizon. Yet like the line of identical houses in the estate she has inherited, this new man in her life proves just as criminally inclined as the previous one, the dead end in which she finds herself, a disappointing reality from which there seems to be no escape.

Although often demonstrating the more uncompromising nature of reality, Kennedy’s world is far from dull or nondescript, the landscapes she paints being filled with space and light. She describes complex relationships, the lives of couples and families that are marked by betrayal, disappointment, and deception, but these are always portrayed against a backdrop of remote and wild natural beauty. Indeed, it is this the constant in each of these exquisitely crafted pieces: Kennedy’s ability to see the flowers amongst the weeds, the tiny shards of coloured glass that shine out amongst the rubble. The stories are undeniably gritty and tough, their predominantly female protagonists existing in a world that leaves them all too often looking for something more. Yet Kennedy offers them chances, proffers branches of briefly glimpsed hope which, although nearly always frustrated, point to other ways out, to the possibility of change. In “Imbolc” – a story named after the Gaelic St. Brigid’s Day festival – Elaine, who is heavily pregnant with her second child, takes a loan from crooks to save her home from repossession. Yet with the loan comes the attractive Stacey, in “leopard print wellingtons” and “a messy bun,” an unexpected and ultimately destructive consequence of Elaine’s efforts to protect her family. In “What the Birds Heard,” reality again is seen to dash the protagonist’s hopes, Kennedy this time presenting family life, rather than financial security, as the briefly glimpsed ideal. The main character is a young artist who has run away from her partner and their fruitless attempts at getting pregnant. She becomes casually involved with a drifter she meets on the beach and tentatively begins imagining some sort of future together – particularly when she finds herself accidentally expecting his child. He has warned her, however, that she is unlikely to “last the winter” up there in the North, and for this character, too, the grasped-at future is soon revealed as illusion, the impossibility of its realisation a harsh reality from which there is no escape.

Although some of the stories examine aspects of male-female relationships that on the surface might appear quite well-worn (unrequited love, adultery), Kennedy’s handling of them has a depth that seeks not to judge or take sides but to capture the wider web of impulses by which they are formed. In “Silhouette,” for example, a teenage girl in skimpy shorts and platform heels finds herself caught up in the cruelties of The Troubles, torn between an emerging awareness of her own femininity and loyalty towards the brother she loves. Kennedy handles these tensions with finesse, capturing the vulnerability of nascent female sexuality and positioning it so skilfully within a world of brutal male violence that what emerges is a beautiful fusion of the two, the tender account of a young woman coming of age in an extraordinarily difficult historical context.

“Silhouette” is, however, the only story that refers to Ireland’s troubled past, and although Ireland is present in every turn of phrase – in the Gaelic terms and numerous references to local tradition – Kennedy’s stories are far from political. They focus very firmly on personal relationships, on the many unspoken transactions that take place daily between parents and children, husbands, wives and lovers, as they try against the odds to get on in the world. They are witty and sharp, the author’s eye for the absurd adding a sly, dark twist to the scenes she describes. In “Powder,” the recently bereaved fiancé of a “casually excellent” American exec, accompanies his mother on a tour of Ireland to scatter his ashes. Sandy, the mother, is unaware that her son had never actually proposed, whilst Eithne his “fiancé” is too embarrassed to correct the mistake. The two tour together, Sandy (who looks as though “Nancy Reagan had been cast in an am-dram production of a Tennessee Williams play”) clutching her handbag constantly to her chest. When they stop to eat at a roadside café, a local youth puts Sandy off her food, warning “they kill the chickens by throwing them against the wall,” a line that still has me laughing out loud. In “Hunter-Gatherers,” it is “townie” Siobhan’s relationship with her gamekeeper husband Sid that provides the comic edge. Sid is committed to living off the land, and under his guidance Siobhan drinks infusions that “smell like sillage,” pegs “chanterelles and hedgehog fungus to flimsy makeshift clothes lines” (they will later rot), all the while compiling a secret stash of chocolate to snack on when her husband’s back is turned. Buying tampons at the local store she wonders if Sid “would like her to spend her periods squatting in a hedgerow with a wad of dock leaves,” her resentment and our mirth increasing with every line.

I loved this collection for its delicacy and the subtle intelligence of the writing. Kennedy shies away from nothing; she gives us all that is ugly and cruel, but does so in a way that is beautiful, lyrical, and lonely. These are stories that make me want to get out into the open, to feel and breathe and remind myself again of what it is to be alive.

The World Is a Cul de Sac

By Louise Kennedy

304 pages. Bloomsbury Publishing

About Jane Downs

Having grown up in the south of England, Jane went on to study Arabic at university, travelling extensively in the Middle East and North Africa before putting down roots in Paris. Her work includes short stories, poetry, reportage and radio drama. Her audio drama "Battle Cries" was produced by the Wireless Theatre Company in 2013. Her short stories and articles have been published by Pen and Brush and Minerva Rising in the US. In August 2021 she joined the Litro team as Book Review Editor, commissioning reviews of fiction translated into English. Other works can be found on her website:https://scribblatorium.wordpress.com