You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

The Nug-Run sat on the bruised east side of town, once a boxy old bank retrofitted for incense and decadence. For a little over a year, it tried to blend in with the other bruises—liquor store, bail bonds, a pawn shop with a barred-up neon promise of “We Buy Gold.” The Nug-Run sold glassware and a kind of permission for the residents of the nearby public housing.

Ray got the job by accident. He walked in needing rolling papers and walked out with a ten-buck-an-hour gig. Penny, the owner, barely glanced at his résumé—but she looked him over with a smirk, took in his movie-star grin and the way he tucked his long dark hair behind his ears like he wasn’t even aware he was doing it, and said, “You start Monday.” He’d been wearing a tie-dye Nug-Run T-shirt they kept folded near the incense and a pair of cargo shorts with a handmade hemp belt his ex-girlfriend once gave him after a music festival. It was, by accident or fate, exactly the kind of uniform that made Penny believe he’d boost sales just by standing behind the counter.

Inside, the store felt like a junkyard hallucinated by a stoned mystic. Bright psychedelic tapestries fluttered from the popcorn ceiling, pinned half-assed and always threatening to fall. Glass pipes and bongs were displayed on mirrored shelves along the walls, like relics in a cathedral of vice. A revolving floor rack creaked when it turned, carrying oversized drug-rug hoodies and tie-dyed T-shirts screen-printed with mushrooms or peace signs. There were two glass display cases for scales, one for detox drinks, and a crooked little section by the outdated register stocked with every brand of rolling paper known to man.

Selling detox drinks came with a script: Don’t ask. Don’t assume. Don’t know. Still, customers loved to confess. A woman in leopard-print leggings leaned in once and whispered, “I smoked crack last night and I got court in the morning.”

Ray put his hands up like a hostage. “Can’t know,” he said gently. “Store policy.”

Another guy, thin and twitchy, said, “Custody hearing tomorrow. I did H. Just once.”

“Buddy,” Ray said, stepping back, “you gotta stop telling me.”

But they always told him again, like he was a priest. Eventually, he’d shake his head and nudge them toward the door.

The clientele varied like a mad carnival. High schoolers breathless for Zig Zags. An old man asking for a “female piece,” code for the kind of bong stem that crackheads modified for their own use. A kid wearing so much gold he clinked when he walked came in for a hundred mini baggies with Superman logos. A stressed-out father in a suit wanted a five-panel drug test for his daughter—and, sheepishly, a triple-blown pipe for himself.

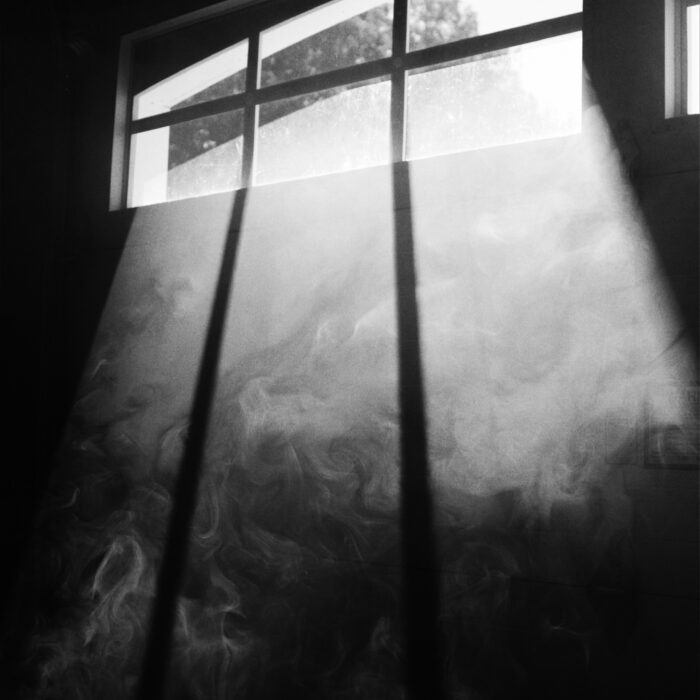

Ray had a ritual. Every night, after the last patron drifted out and the strip mall, he’d lock the doors, slip into the employee bathroom, and take a hit from a wooden one-hitter. Then he’d cue up Workingman’s Dead and let Garcia carry him through the close.

It was the one part of the job that didn’t make him feel like a fraud.

There was a kind of holiness in the sudden silence, the incense curling its last tendrils into the air. He turned up the Dead, vacuumed the same rug that never looked clean, counted the drawer, dropped the deposit in the floor safe, and restocked for the opening shift.

Then came the side hustle.

He reached into his pocket and unfolded a small, grease-stained scrap of notebook paper:

4 Dichroic glass pipes.

2 glass-on-glass bong bowls.

4 glass drop necklaces.

He walked the dim aisles like a jeweler, wrapping each piece in bubble wrap with the care of someone tucking in a child, and careful to rearrange the shelves afterward to hide the gaps. The trick was to make the glass look abundant. Detox drinks and scales were off-limits—but glass? No barcodes meant no tracking, and that was untraceable profit.

On Saturday mornings, he drove the hour south on 75, past scrub pines and outlet malls, heading for Alex’s college in St. Petersburg. He kept to the speed limit and wore a “Support Your Police” bumper sticker like a disguise. Only idiots invited trouble, he thought, when a yellow Corvette tried to goad him into a race.

Alex lived in a swampy dorm just off the private beach, his room a cave of laundry, half-eaten pizza, and declining ambition. It smelled like sweat, Ben-Gay, and bong water. He was still sleeping when Ray walked in his room.

Alex was the same as always—smirking, stoned, three steps ahead. “Check this out,” he said, holding up a squat black light and illuminating a scorpion in a jar. Its shell glowed radioactive blue. “Also turned my coffee grinder into a weed grinder. All the shake drops down here,” he said, tapping a compartment.

They set up Ray’s merchandise on a tie-dye blanket in the corner of the quad. Beside it, a Frisbee sat flipped upside-down as an informal collection plate. “Twenty bucks for anything,” they’d say, “or trade me something fun.”

The campus kids would trickle in—kids whose parents had just filled their checking accounts—peeling off twenties, offering tabs, a nug of hash, a bag of pills. The frisbee filled quickly and they’d be out of inventory within thirty minutes. Ray kept the cash but shared everything else with Alex. Nothing would be left by Sunday night.

They’d been friends since second grade. Used to talk over walkie-talkies from their bedroom windows, trying out flashlight Morse code. Played baseball, basketball, soccer—each season its own chapter. Summers were for chaos. Alex had always been better with girls. Always ahead. When Ray got his first kiss, Alex got a handjob. When Ray got a handjob, Alex was in a threesome. That’s just how it was.

Once, in eighth grade, Alex cried after a breakup. Punched a mailbox and sat in Ray’s driveway with his hands shaking. His mom was in rehab. His grandfather had passed out drunk at Christmas. They made a pinky promise not to become that. No drugs. No booze. Not like them. It didn’t last long.

By the next fall, they were bribing the homeless guys under the 7th Street bridge for booze. Breaking into neighborhood pool houses dressed as ninjas. Dragging mini-fridges into the woods like pirate treasure.

They revised the pinky promise. Not ‘no drugs’—just not bad drugs.

“This weekend’s gonna be lit,” Alex said, slapping a pack of Camels. “It’s Kappa Carnival. Whole beach turned into a fairground. Oh—and I totally hooked up with that redhead, Vanessa. Pulled me into a closet at Kappa Chi. Dude—check out my back. Shredded. Like, tantric shit.”

He tucked the cigarette behind his ear, grinning.

Ray remembered Vanessa—yoga on the quad, thermos of green juice, eyes like emeralds. “What about Becca?”

Alex popped a beer. “She’s with someone else. Whatever.” He paused. “Vanessa and her new guy walked past us during ultimate fris. I yelled hi. Kid’s a loser. Didn’t say shit.”

Ray grinned. “You seen Hillary around?”

Alex shrugged. “No clue, man. Haven’t really been to class this week.” He leaned in, eyes bright. “This week, these freshmen were pushing a shopping cart full of booze toward Sigma. Me and Carrot told them we were R.A.s. Confiscated the whole thing. Four cases of Yuengling, two bottles of Smirnoff. One of ‘em figured it out later, but now he just Venmos me to buy for him. I buy two packs at once—one for him, one for me. Win-win. Except he wakes me up like, ‘Dude…dude…beer run?’”

For all his stoner swagger, Alex stayed on the Dean’s List like it was a dare. He could quote Derrida in one breath and recite Phish setlists in the next. That afternoon, he ground together some hash and pot in his modified grinder, the blades humming like a low drone, and rolled a few joints with surgical care.

“You ever read about Bohemian Grove?” he asked, licking the edge of the paper. “That’s where the real decisions happen. Old white dudes running around naked, worshipping owls and planning the next war.”

Ray laughed. “You sound like my uncle.”

“I’m serious, dude. And don’t get me started on the Large Hadron Collider. Shit shifted our reality.”

“Yeah? That makes sense.”

Ray pointed at the cellophane sleeve from Alex’s cigarette pack. “You done with that?”

“What for?”

“The ‘cid. Hillary and I.”

Alex made a hurt face. “What about me?”

“You? You’re covered. Next weekend’s stash is all yours,” Ray said, folding the flimsy plastic.

They left the dorm together, stepping into the hazy pulse of evening on campus. Alex slung a modified document tube across his chest; it held six beers and looked like something a character in a dystopian novel might use to smuggle contraband literature.

In the hallways, doors stood open. Clusters of kids huddled around TVs, someone’s acoustic guitar, the hypnotic swirl of a lava lamp. There were the sounds of stories being shouted over music, cups clinking, bodies shifting. Alex—never subtle—swung both double doors wide when exiting a building, like a stoned superhero announcing himself.

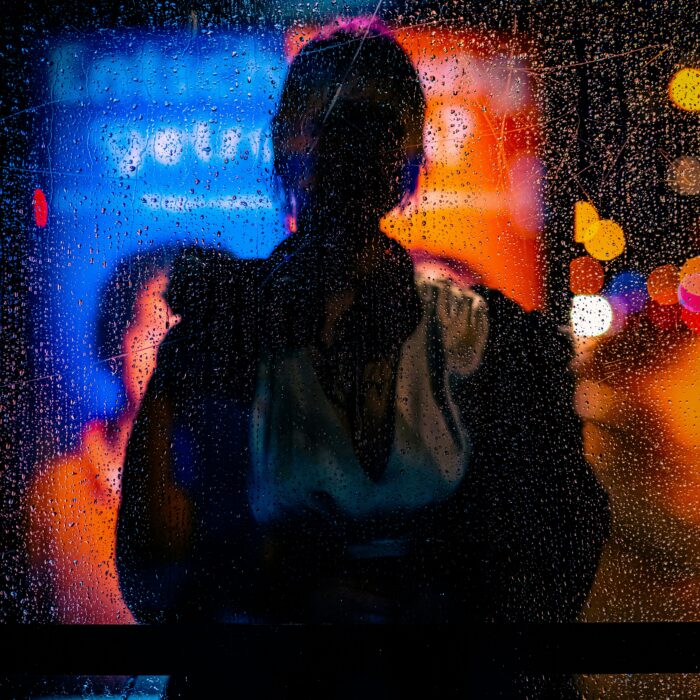

They drifted across the lawn toward the beach, nodding at passing strangers, grinning at familiar faces. Down by the water, kids lit joints and passed them. Orange embers flared in the dark like tiny signals. Somewhere in the distance, bongos echoed, steady and tribal. Ray inhaled and let it sit in his chest. They laughed, traded the same stories they always did—the ones they thought were hysterical, though most girlfriends past had disagreed.

Sometimes, when Ray wasn’t high enough to float above his own thoughts, he wondered if the past was the only thing keeping him and Alex close. They’d been syncing punchlines and sharing lighters for so long that maybe memory had replaced present meaning.

The Kappa Carnival surged on the campus lawn like a fever dream. Music collided—trap beats drowning out jam-band guitar solos, drum machines clashing with live percussion. Tents stretched across the field, handwritten signs advertising dunk tanks, henna tattoos, mystery prizes. Black lights and strobe lights turned the field into a spectral rave, students’ clothes glowing with phosphorescent.

Ray tried to convince himself this was the climax of youth—freedom, spontaneity, all the chaos and laughter—but somewhere behind his eyes, the old anxiety stirred. In crowds like this, his body felt hijacked. He’d smile, crack a joke, pass a joint. And yet inside, he was still the kid in middle school afraid to kiss someone during spin-the-bottle. People called him an extrovert. He let them. It was a mask he’d tailored down to the seams.

“Dude,” Ray said, nudging Alex and nodding toward a slushie cart, “It’s the Love-Fish.”

The infamous Jessica Meyer was licking melted slush from the rim of her plastic cup. Her nickname came courtesy of her reputation—oral and otherwise. She wore black yoga pants and a white bikini top that glowed in the black light. Bracelets jingled up both arms. She drifted through the crowd like a goddess, bestowing cheek-kisses and Jell-O shots like blessings.

“Hey guys,” she said, stopping in front of Alex and brushing his shoulder with her knuckles. “You hear my roommate’s moving out?”

“No—what happened?” Alex asked, sweeping his oily blond hair back into a bandana.

Jessica rolled her eyes dramatically. “Her OCD was, like, weaponized. She had to wash her hands every time a plane flew overhead. I’m free, you guys. Free.”

She leaned closer and pinched the fabric of Alex’s tank top between her fingers, her voice slurring. “Anyway, our class project’s due Monday. Want to maybe…collaborate?”

Ray got the hint. He gave Alex a friendly smack on the ass and said, “I’m gonna find Hillary.”

Jessica didn’t even glance at him. “She’s over by the ‘Pitchers with Professors’ tent. With Julie, of course. They’re actually carding people to get in. So lame.”

Ray nodded and headed toward the tent, pushing through the pulsing maze of students. His thoughts wandered back to the first time he met Hillary.

*

It was at a party in Nu dorms—the rugby player dorm. The air had smelled like stale beer and lube. Hillary had been on a balcony, laughing and cheering as French Shaun tried to leap from the railing to a palm tree. He missed, snapped his leg like a branch and screamed until campus medics dragged him away.

Hillary had these eyes—bright blue, almost unnaturally so—set against black hair in a chaotic bun. She wore a vintage James Taylor shirt knotted at the waist, her freckled stomach exposed like some indie magazine spread. A small hoop glinted in her nose, and a Gemini symbol curled on her left wrist.

They’d been standing in a circle. Ray asked her, “What’s your story?” He’d learned from Alex that people never had a good answer for that question—it disarmed them, made them vulnerable.

She shook his hand like they were at a business meeting. “I’m Hillary. Not sure about my story…but I lived in a tree in Berkeley for a year. It was beautiful. We had platforms for everything—painting, dancing, even doing laundry. My space was above this guy David. His sitar was basically our salvation.”

She touched her chest like it still echoed there.

Ray blinked. “How’d you end up there?”

“My friend’s related to Country Joe McDonald—ever hear of him?”

Ray nodded, sipping from a plastic cup.

“So we hitchhiked to the Berkeley Arts Festival. Hopped trains. Danced on cabooses. Waved to strangers on highways. But once we hit the industrial hubs, it got grim. Like Mordor, man. Just shadows and metal.”

As she talked, Ray realized she wasn’t talking about hardship. She was talking about an experience curated by privilege. Trust fund kids slumming it on boxcars and sleeping in trees.

Still, she was magnetic.

Her friend Julie, less so. She sized Ray up with the full scrutiny of a protective bestie. Lacrosse frame. Zero makeup and energy full of judgement.

“Who are you here to visit?” Julie asked.

“Alex Woodman.”

“How do you know him?”

Ray smiled. He got this a lot—townie suspicion. He couldn’t be mad. “I’m always here on the weekends,” he said, adding a quote from Ani DiFranco, something obscure but poignant. He’d seen her at Jannus Landing the week before and still had her voice echoing in his head.

Julie’s guard dropped an inch. “We just saw her at Jannus.”

“Me too,” he said. “She’s amazing.”

Later, Hillary pulled him toward her dorm. She wanted him to hear Fleetwood Mac in Chicago on vinyl. Said he’d “get it.” Julie pulled her aside first, tried to talk her down, but Hillary returned and dismissed it. “She’s just emotional. Leaving for Greece for study-abroad soon.”

Her dorm smelled like patchouli and lavender. Vines hung from the ceiling. Visitors had to push past leaves to reach the bed. Garden gnomes stood facing corners like punished children.

“They’re naughty gnomes,” Hillary said. “I rescued them.”

Ray ran his fingers along her alphabetized vinyl collection. “Holy shit,” he whispered.

The bed was a bunk with the bottom turned into a den—curtains like theater drapes pulled open to reveal a desk, a beanbag, a shrine of candles.

They drank and played records. Sang along to Carole King, Jim Croce, and James Taylor. She dropped the needle and skipped away from the player like it was about to explode. During “So Far Away,” she placed her hand over her heart and closed her eyes.

Ray, suddenly desperate to match her wavelength, tried to summon a tear.

“When I graduated high school,” Hillary said, her voice low and reverent, “I was valedictorian. But instead of giving a speech, I just played Cat Stevens’ “The Wind” on my record player and raised my fist in the air.”

“That’s incredible,” Ray said, watching her. Of course she’d done something like that. She was one of those people who made chaos feel controlled. She didn’t need him—he could feel it. She could take or leave him and be just fine either way. And that, of course, made her dangerous.

She told him she was studying reiki. “I want to heal your body with universal energy,” she said, her fingers hovering over his skin like butterflies. She hummed, eyes half-closed, circling her hands over his chest as though stirring something unseen. Ray closed his eyes and tried not to think about sex but inevitably did, picturing the two of them tangled, trying to broadcast his yearning. If she noticed, she didn’t say.

Later, they sat cross-legged on the floor, staring into each other’s eyes in silence, an experiment in “wordless communion,” as Hillary called it. “Language just gets in the way,” she whispered.

That night, they swam in the ocean in their underwear, phosphorescence catching in the water around their limbs like stars coming home. She twirled, arms overhead, face to the sky, and then spun toward him with laughter spilling from her mouth. When she kissed him, it was all soft and quiet, and he melted into it.

*

At the carnival, Ray found her near the ‘Pitchers with Professors’ tent. She grinned and raised her crossed index fingers like a ward against evil.

“Eww. Store-made tie-dye,” she hissed, as if banishing a demon.

“Work uniform,” he lied.

He handed her the last glass-drip necklace he’d been saving. She slipped it around her ankle, twice, then raised her leg like a dancer, admiring it with a satisfied nod and a slow shake.

When he revealed the cellophane, folded carefully in his pocket, her eyes lit up. She took his hand without a word.

Beyond the edge of the private beach, into the dunes, she led him to a clearing she’d decorated earlier—a giant mandala made of palm fronds, seaweed, and driftwood. The shapes spiraled outward in sacred geometry, illuminated faintly by the glow from the distant carnival, which rose behind them like a pure glowing energy.

They lay in the center, heads side by side, and took the tabs Ray had saved.

“Just one,” he said. “One is good. More is something else entirely.”

“It’s what you make of it.”

He smiled. “I made good money tonight.”

“Money isn’t real, Ray,” she said, letting a handful of sand trickle through her fingers like falling time. “The only truth…is this.” She touched her chest, then laughed wildly as the sand caught on the wind.

Ray chuckled. “I get that money shouldn’t matter but—”

“No buts,” she said, raising a finger.

Ray got it. At least, he wanted to. But he couldn’t allow himself to tumble fully into the existential hole. He had rent to make, aging parents, a quiet clock ticking somewhere behind his eyes. He wanted a family behind a picket fence someday. You couldn’t raise a kid in a tree. But this—this night on the beach with a strange and beautiful girl—was still something. He tried to believe it mattered, and was enough.

“I need to visit my parents,” she said softly. “They’re down near you, by the water. My mom’s sick again.”

As she spoke, her arms rose as if buoyed by invisible flames. She circled her wrists in the air, eyes distant.

“I’m sorry,” he said. “If they ever need anything, they can call me.” It was something he said to sound reliable, though if they did call, he knew he’d help—but resent it.

She told him about how she used to run over the same mailbox on her street all through high school. “They tried everything—reflectors, flags. I was just bad at backing up. And I was on Xanax, a lot.”

Her parents eventually sent her to Peru for an ayahuasca retreat where she confronted the black fog of her addiction and, later, her mother’s cancer, which appeared to her as a burning bush.

Ray began to feel the acid move through him, a strange energy sliding down from the roof of his mouth. He shifted, stretching into the cool sand. It had a metallic taste.

He tried opening up to her—his fears, his creeping anxiety about life, how he admired her confidence—but she responded with abstract metaphors and dreamy stories. Something about a squirrel and a turtle who turned into a squirrel too. “Do you get it?” she asked.

He didn’t.

She looked over, gentle. “Ray. Is it okay if I take my shirt off? I’d just feel…freer.”

“I understand,” he answered. “By all means…”

Her nipples were pierced, small silver rings catching faint moonlight. Ray pretended not to stare. He wanted to be the kind of guy who saw her, not just her body, so he kept his hands to himself even as she rolled in the sand, fingers gliding over her own stomach and chest.

“I’d really like to have sex with you now,” she said finally. “What do you think?”

Ray’s heartbeat jumped, more from the acid than the moment, and he flushed with an almost boyish panic. He remembered something his mother once said: If she sleeps with you right away, you’re not special.

He breathed in, held it. Looked at Hillary’s eyes. Kissed her again, slower this time. She slid her underwear aside, revealing a tangle of hair.

“I’m all natural, man.”

Ray was amazed. He hadn’t seen pubic hair since Leah Kopple in middle school, fumbling in a dark closet. Back then, he didn’t know what he was doing, just listened to her breathing, trying to learn the rhythm of her pleasure.

Now, on Hillary’s mandala, they moved together as though slipping into some mythic tide. Eyes closed. The moment bloomed and deepened. For Ray, it felt like falling into outer space, into some sacred pocket where nothing else existed. He saw a floating orb of energy, understood himself as a flicker of ink on a page in a vast library of lives.

He came on her stomach. She tilted her head, fascinated, then wiped it gently away with seaweed. After, they held each other and cried without knowing exactly why.

She saw it too. “We glimpsed the truth,” she whispered, pulling him close.

They lay there for another hour, unable to speak. The silence had weight.

“This isn’t real,” Ray said finally.

“…If nothing matters, then all that matters is this,” she replied.

He shook his head. “I don’t feel like I earned it. I cheated my way to enlightenment.”

“It was beautiful,” she said. “And meant to be.”

They wandered back toward the beach party, fingers loosely interlaced.

“Let’s try to be normal,” he said.

A jogger passed in the night, wearing a black tracksuit, her body swallowed by the dark so only her head was visible.

“Why does a head need to work out if it doesn’t have a body?” he asked.

Hillary collapsed into breathless laughter.

The DJ’s lights pulsed into the night sky, as if the music itself had color and volume. The tall grass waved like orange fire. Ray felt grounded, even lucid. “I could talk to a cop right now,” he said, and meant it.

Alex appeared, wild-eyed, a cigarette dangling from his lips with two more behind his ears. “Love-Fish just told me her mom was the high school janitor, and her dad beat her whenever she ate too much because he wanted her skinny enough to prostitute. She started crying. I bailed.”

Hillary looked at him and burst out laughing again.

“You two are tripping,” Alex said, studying their pupils. “Totally.”

They walked toward a large gathering by the water. On the way, Ray gave Alex a look which he swiftly interpreted: We just had sex. Alex responded with a pleased grin and nodded his head in approval.

In the group, blunts and joints were passed around as much as conversation. Most of bodies were from the Nu dorms. French Shaun leaned on crutches with a cast on his leg. Ray ignored his instinct to hover over Hillary in the crowd despite her talking excitedly to one of the rugby players, Ben, who was known for fucking everyone. Ray knew the look in Ben’s eye, he was interested in her, shamelessly flirting, and no one else was aware that they had sex and glimpsed “the truth” a little while earlier. It pained him that no one knew. Hillary appeared to forget as well, politely smiling over to Ray while he stood talking with Alex. She winked, probably to soothe his apprehension, her chest and neck still mildly inflamed from his stubble. Ray couldn’t do anything except act like it didn’t bother him. By one point, in the circle, Alex had four joints to himself, and he said, “Jesus fuck. It’s like Christmas.” The night got blurrier and when Hillary departed, she said good night to the entire group and blew a kiss before she vanished. He considered texting her goodnight, but he didn’t want to come off as possessive.

The night shifted into that limbo that exists between 1:00am to 4:00am. As it did, the wearier and more disillusioned Ray became, entering a state in which he was physically present, and knew what was happening, but completely checked out. Alex and Ray ended up in Carrot’s room. Ray never knew his real name, but he was pre-law and his dorm looked like the inside of a genie’s bottle. The walls were covered in tapestries. There were three large hammocks extended from wall-to-wall, and the floor was covered in pillows, hookahs, and potted plants. Most people said, “You stop by Carrot’s for a minute and a day goes by,” and this was very true.

After a while, Ray woke up in a hammock, hearing a girl in the dark room asking Alex if he could feel her tongue-ring.

“Yup,” Alex said, followed by a crack of a new beer opening.

The clattering of bracelets continued in a rhythmic pattern as Alex groaned.

“Shut up,” Ray said. His head throbbed; he wanted to sleep it off.

“You shut up,” Alex quickly replied.

Ray left and went to Alex’s empty room to sleep in peace. Alex stumbled in once the sun came up, saying that he had to collect samples in a marsh for a class. Once he returned, around noon, he woke Ray and asked if he knew Julie, Hillary’s friend, “that butch chick,” and handed him a bottle of water.

“Yeah, I met her the night I met Hillary.” Ray carefully tried to adjust his eyes to the daylight, slowly forcing them open.

“Well…that’s Hillary’s fuckin’ girlfriend, and she is looking for you, bro. She’s pissed and she’s in the building. Upstairs. Like, raging, dude.”

“Fuck,” Ray said, sitting up. “Fuck.” The energy on campus suddenly changed, as paranoia quickly replaced quiet pleasure. Now, it felt like there could be a charged confrontation around any corner.

“Come on. Let’s bounce,” Alex said.

They hopped out the dorm window, in the same clothes as the day before, and grabbed two of the public, yellow bicycles that littered the campus and rode off to the Breakaway Bar off of the public beach.

The bar had a thatched roof and a small mote with running water around the bar, which patrons rested their drinks in to keep cold. Alex always made tiny boats from his empty cigarette boxes and released them.

They ordered bloody marys.

Ray explained everything that happened. Alex chuckled at the free entertainment. “You fuckin’ idiot. You got a pissed off lesbian after you now. Hope enlightenment was worth it.”

“Yeah…”

“Dude,” he said, trying to light a cigarette, “that Hillary chick is nuts anyway. You really think she’s the type to settle down? She’s wild, man. You’ll drive yourself crazy chasing that.”

The wind was too strong to light it alone, so Ray provided cover with his cupped hands.

They shared a chicken finger appetizer, which they both sluggishly breathed over before finally forcing themselves to eat. And they had a brief discussion with a homeless man who begged for cash before they rode back to campus.

Ray got to his car to head home. “Too much fun,” he said. Alex asked about the weekend’s stash and Ray told him to save some of it for next weekend, knowing that he wouldn’t, but that Alex would make it up somehow.

Ray felt a sense of relief once he entered the highway. The farther away he got from campus, the closer he got to his own safe and peaceful bed. He pictured Hillary underneath him, kissing him, looking up, pulling him in deeper. He didn’t know what to think, but he needed rest.

Getting off at his exit, Ray leaned his dirty face against the window while paused at a red light. Next to him, a car slowly pulled up. He turned to instinctually acknowledged another’s presence, allowed his gaze to meet the other driver’s eyes. The driver was young, maybe his age, in a suit, had short, combed hair, and was freshly shaven, with a fresh cup of coffee held to his lips. He was talking on his phone and appeared quietly offended once their eyes met.

Ray smiled but quickly looked away when he saw the driver’s reaction, then observed himself in the rearview mirror.

Long, untidy hair, littered with sand, covered his dark, sunken-in and bloodshot eyes, his beard was unkempt and had crumbs. He attempted to convince himself that he was living a waywardly romantic life, but, deep down, he knew the truth.

The light turned green. The driver swiftly merged into the left lane disappearing under the bridge, leaving Ray ruined at the quiet intersection.

Mark Massaro earned a master’s degree in English Language & Literature from Florida Gulf Coast University, and he is currently a Professor of English at a state college in Florida. His writing has been published in The Georgia Review, The Hill, Los Angeles Review of Books, The Masters Review, Litro, Newsweek, The Colorado Review, and many others.