You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

For most of my life, I carried a persistent sense of being out of step, though I couldn’t explain why. I masked, I adapted, I performed. I worked so hard at it that even I believed the performance. Beneath it all was a steady exhaustion I didn’t know how to name. Looking back, I see now that the world pressed against me in ways I could not escape. Small changes left me on edge. Even the simplest conversations could drain me until I sank into silence. I rehearsed words in advance and replayed them afterward, always questioning how I had come across. I didn’t have a name for this. I only knew that no matter how hard I tried, I never seemed to keep up. It wasn’t until my mid-fifties, with a late diagnosis of autism and ADHD, that the truth finally came into focus.

The signs were always there, though I couldn’t recognize them. What looked like hesitation or avoidance from the outside was, for me, the daily reality of navigating a world that constantly asked more of me than I could offer.

My world closed in slowly, the spaces I could manage shrinking. Buses became unbearable, with bodies pressing close, the low mechanical hum vibrating like a threat. Subways screeched through tunnels of humid air that caught in my throat. Theatres became a claustrophobic trap, stores a dizzying maze under the glare of fluorescent lights. Each new avoidance was like crossing another place off the map of my life, leaving me with fewer and fewer safe zones.

I did not have the words to explain it. What I was living was an irrational fear, a dread of collapse ingrained in my body, refusing to let go. All I could do was make excuses: say I wasn’t feeling well, leave early, find a way out before anyone could see how close I was to coming undone.

Doctors called it panic disorder. Phobia. Everyone told me to push through. They prescribed reconditioning, exposure therapy, as if my terror could be trained out of me. But the fear was never imagined. It was a raw, visceral overload, a life that demanded more than I could manage, more than I could give.

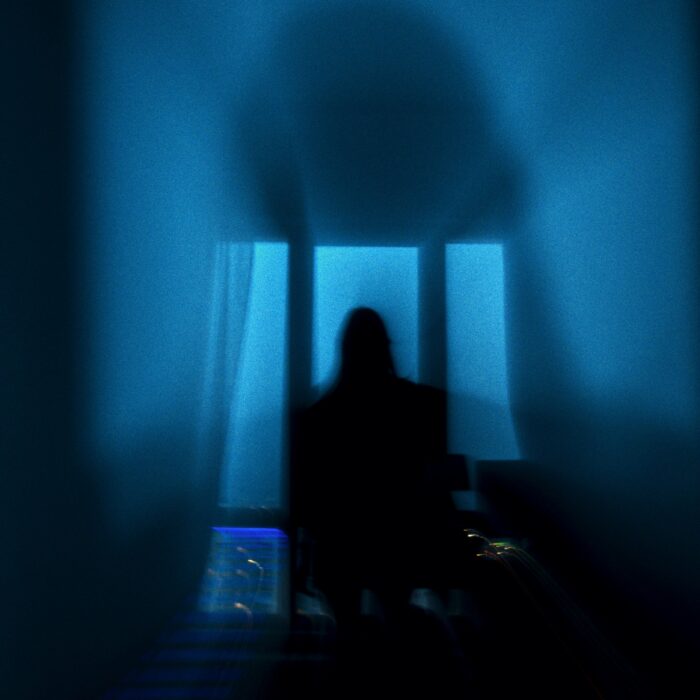

Even in the supposed sanctuary of my own home, the fear had taken root, a silent corrosion that reached deeper every day. My body braced constantly, waiting for the next invisible fracture.

And beneath it all was a greater terror: that if I fell apart in front of anyone, if I really let the collapse show, I could be locked away. From adolescence, I had absorbed that warning. One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest haunted me with its portrayal of patients stripped of their autonomy, their very spirits extinguished by the clinical indifference of the institution. Frances etched itself deeper still, a daughter silenced and institutionalized by her own mother’s will. That fear became a cold thread woven into my daily existence. It wasn’t only my freedom at stake, but the elusive core of myself, a fragile boundary always in jeopardy of unraveling.

Each step became a calculated risk: seek just enough support to avoid collapse, but always remain visibly in control. So I masked. I held myself together behind practiced composure. I carried this hidden weight, this constant need for control, until my early twenties. That was when I met him, and the fragile thread of stability I clung to began to unravel.

For our first date we went to see the Disney animated movie Aladdin. I noticed everything about him: the angle of his walk, the faint touch of makeup covering a blemish. I didn’t know it then, but that pattern of noticing, absorbing every detail, was simply who I was.

We went on more dates, and slowly our relationship deepened. Soon we were a couple, and an unexpected longing grew within me, tenuous but hopeful, and for a fleeting moment it felt as if the tightly held life I guarded so fiercely might finally begin to expand.

He was intelligent, interesting, driven, filled with purpose and ambition. With him, I began to imagine the possibility of a life that stretched beyond my carefully controlled spaces. I so badly wanted the freedom of spontaneity, the ease of simply doing things together, and the comfort of belonging. But my body, and my mind, refused to cooperate.

Trips to his parents’ cabin, two hours away, left me depleted before we even arrived. It was not the risk of the road that unsettled me, but the endurance of the long drive itself. Each mile tightened the coil inside me, bracing against the inevitable rise of panic. By the time we arrived, I was too rattled to settle.

Once there, his friends who lived nearby suggested boating. Everyone was laughing, carefree. I froze. My body locked at the sound of the engine and the unpredictability of it all. I hid behind excuses, a sudden headache, a wave of tiredness, anything to avoid exposing the shameful truth of my condition. And when he left with them, I was stranded in silence, far from home, the isolation compounding the fear until it felt suffocating.

A quiet resentment, sharp and unexpected, rose in me. We only had the weekend together, and if he truly cared, I felt he should have stayed with me. Yet another part of me knew it was unfair to want that. Of course he should go, enjoy himself, laugh with his friends. I was hurt that he left, and I hated myself for wanting him to stay. And with his presence missing, deeper still was the irrational terror of being utterly alone, untethered from the safety of anything familiar. The long drive, combined with the awareness of being so far from my anchors, made the fear overwhelming. It froze me from the inside out, stopping me in my tracks with a force I could not explain, not even to myself. I was only trying, with every fiber of my being, to keep this impossible front from cracking.

The truth is, I wanted to be with him on that boat. I wanted to be the girlfriend who laughed easily and said yes without hesitation. But something inside me refused to let go. The dread of losing control was stronger than the desire to belong. So I stayed behind. And each time I did, I felt myself slipping further from the rhythm of his world, from the everyday moments I wanted so much to share with him.

I told myself he deserved better, not because I did not love him but because I did. I loved him more than anyone before or since, and that made it unbearable. I could see the life we could have had. I just couldn’t reach it.

He was studying cell signaling and proteomics, dreaming of learning abroad and publishing in major scientific journals. I was measuring how many miles I could tolerate before the panic rose, how many social outings I could endure before collapsing.

The decision to end our relationship was agonizing, a slow, internal torture that hollowed me out.

I made the decision for two reasons, each a heavy stone in my gut. First, I carried the belief that letting him go was giving him the freedom he deserved. I couldn’t bear the thought of my limitations, the unseen boundaries of my life, holding him back from the full, expansive future his ambition and intellect so clearly promised.

But the harder truth was this: I knew, with a certainty that hit me in a place too deep to reason with, that I could not have handled the rejection of him eventually leaving me. It wasn’t a prediction of his actions, but an absolute knowing of my own fragility. I was so deeply afraid of appearing inadequate, of being seen as falling short in the ways that truly mattered to a conventional relationship. I simply couldn’t match the relentless pace, the casual spontaneity, the unspoken expectations that came with a “normal” partnership.

Trying to keep up, pretending I could, was a slow, quiet breaking, eroding me from within. My unrelenting push to appear fine led to immense emotional labor and chronic exhaustion. It didn’t feel fair to him to hold on, to trap him in my shrinking world. And the truth is, it wasn’t fair to me either. That relentless sense of falling behind, of never quite measuring up, was quietly wearing me down, leaving me thin and threadbare in a way that made me feel increasingly inadequate, as if no matter how much I gave, it would never be enough.

So I ended it. Not gently, not with the honesty he deserved. Over the phone because I didn’t have the emotional strength to face him. Instead, I told him I never wanted to see him again. A lie, a shield, a desperate attempt to protect myself.

And then it was only me and the raw echo of my grief. I crumpled under it. His silence was a wordless agreement with the choice I had made. Part of me had still hoped he might see past the fear, past the mask, and love me anyway. But the quiet proved otherwise.

There was no closure in it, no peace, only self-preservation. I believed I was freeing him, but I was also cutting myself off from what we might have been. His silence confirmed the ending, but my fear had already set it in motion.

What I could not see then was that I had been fighting against something inside me, shadowing me at every turn, an unnamed force that determined my every choice. At the time I told myself it was selfless, that I was giving him freedom. In truth, I resigned myself to the belief that love could never flourish within the limits that defined my life.

Telling this story now is not just remembering. It is reliving. It is pulling myself back through doors I barely survived closing. It is holding my own hand through the silence it left behind. Naming the pain gives it shape. And when something painful finally has shape, it becomes a little easier to hold.

By Patricia MacDowell

Patricia MacDowell is an independent filmmaker and writer based in Montreal. Her feature film Sweeping Forward won Most Popular Canadian Feature at the 2014 Montreal World Film Festival. She is currently completing a memoir, From Shadows, which explores self-discovery shaped by a late diagnosis of autism and ADHD.