You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

“But what’s the difference?” I quietly asked Christine, who was sitting beside me in the first row of the back room, smelling slightly of persimmon. “As long as they buy it?”

I learned there are three ways to make money. Get more people to buy, get people to buy more often, or get people to buy something more expensive. Upgrade. By people, I mean mothers. It doesn’t matter what you’re selling–burritos, pajamas, lawn furniture–mothers are the main vein. 80% of everything. We ordered them to our specifications. Household income, family constitution, passions and interests were all screened. First-time mothers were ideal for expensive and unnecessary innovations. When the first Bugaboo, “the Frog” appeared in 2002, tripling the price of the previous luxury model–the suddenly dingy McClaren—my colleagues nodded in respect. Then there were the mothers who occupied the broad arc of the bell curve, 45-75k, 1+ children, a passion for care, cleaning, order. Dee, Maria, the Carols, Sara, Sangeeta, Tola, Patti. You’ll meet them soon. They held our fates in their 80 million hands. We recruited them from three different media markets to explore any regional differences in dishwashing attitudes, beliefs and behaviors.

I learned that the markets were rarely in the glamorous urban centers I hoped might be the destinations of my business travel, but rather isolated mid-sized cities because they were a better representation of American values than coastal cities with their elite ways and means. The cities for this–my first research trip ever—were Nashville, TN, Columbus, OH, and Fort Collins, CO, which we were going to visit West to East for logistical reasons I didn’t understand. Telling you the name of the dishwasher brand that is the occasion of this research is more trouble with a global corporation’s fearsome team of lawyers than it’s worth, not least because you assuredly know it. As of this writing, July 2020, there is a 47% chance that you or someone dear to you pour its crystals or squirt its translucent gel or as of 2001 place its multicolored pod into your dishwasher’s designated compartment as part of your daily chores.

The first learning worthy of inclusion in my report was that serious dishwashers (the people not the machines) were deeply invested in the way they load their appliances. Every mother claimed to have cracked the code on their dishwasher’s load capacity and cleaning efficacy. As the moderator, Claire M, pointed out in our first debrief in the Denver, CO airport Cantina Grill, half of each 90-minute session was taken up with detailed descriptions of how respondents layered plates and saucers in parallel rows, distinct from bowls which needed to be “nested” so they didn’t redirect spray away from its intended course. Failure to perform this task would leave crusted food on plates which you could never get off without borrowing your fancy sister-in-law’s power washer. In fact, Claire M– suggested we didn’t call them dishwashers (the people not the machine), but rather dishloaders, to acknowledge the behavior’s importance and avoid the noted lexical confusion. This seemed a minor observation but judging by the way Sanjay, the brand manager, made a careful note I could tell Claire had hit the mark. Chiefly, and another pivotal learning for me, the obsession with dish-loading was considered a problem by my clients in the sense that these homemakers gave their precise loading routines credit for their clean dishes.

“It’s not the detergent,” Claire said between loud announcements on the Denver Airport PA. “We didn’t hear many brand names today, did we?”

The assembled group all made eye contact but didn’t answer.

“The loader is the hero,” Claire continued.

“And un-loader” added Dennis Lim. Dennis worked for Sanjay as the assistant brand manager and was a very serious young man indeed.

Claire rested the eraser end of her pencil against her lips and quibbled: “Didn’t we hear that unloading is a relegated chore?”

I started to speak but I wasn’t fast enough for Dennis. “It’s the reveal,” he said, eyeing the rest of us along the cramped booth in the Cantina Grill.

Randall made a face. He led the R & D team and wanted to hear more about spotting which his new innovation was designed to address.

“Maybe we should focus on favorite foods,” Christine offered. “We need a torture test.”

A torture test, I learned, was a homemaking problem that had resisted all remedies, a stain that wouldn’t go away. If a brand could crack that nut, then, it was surmised, consumers would believe it could serve all their wants and needs, known and unknown. Torture tests occupied my mind over the two-hour flight to Columbus and the almost equally long drive to the focus group facility, located as always on exurban fringes of the city, so closely resembling the others, that it seemed we were repeatedly returning to where we began.

“I want you to imagine,” said Claire on the other side of the glass to the Ohio mothers, “that this is a magical room.”

“Oooh,” the mothers said.

“In this room, you will discover things you didn’t know you knew.”

This being my first work in the field, it was suggested by Christine that I occupy a “listening mode” but my long training finally caught up with me and as the respondents turned again to their loading skills–with one Elizabeth Trout suggesting a competition, if only so she could crush all challengers, creating a tension in the room that manifested as a staticky silence on our side of the glass—I had a question I needed answered. “But what’s the difference?” I quietly asked Christine, who was sitting beside me in the first row of the back room, smelling slightly of persimmon. “As long as they buy it?” Quiet turned out to be the right register to ask this question because as my whisper entered Christine’s smooth, translucently pink ear, she brushed back the hair from her face and with a perplexed expression whispered back: “Can. You. Step. Out. With. Me. Please.”

The focus group was invented by Robert Merton in the 1940’s at Columbia to study the impact of wartime propaganda, including ways to motivate Americans to purchase war bonds. His first study was based on an 18-hour radio marathon which raised a record-breaking sum of $39 million. It was assumed that patriotism drove the contributions, but in what he called focused interviews, the first of their kind, Merton learned a deeper motivation was at work. The audience was compelled by the host, a popular singer named Kate Smith, also known as The First Lady of Radio. They were drawn by what we might today call her authenticity. “She’s just fat, plain Kate Smith,” said one respondent.

“Take some of these actresses, do they care about anything but themselves? Many of these actresses are beautiful, lovely figures, but Kate Smith hasn’t any of this…I look on this as a mother: I don’t want beauty. Perhaps at sixteen I wanted it, or at nineteen, but now I don’t want it anymore. [In agitated tones] I’m thinking of my children, I’m not thinking of glamour [this said with withering contempt]. (Merton’s Brackets)

Does it need to be mentioned that all these mothers were facing a long stretch of solitary domestic labor as their husbands were deployed? Born Meyer Robert Schkolnick to Yiddish-Speaking Russian Jews, Merton invented his new identity as a stage name for his magic shows which he performed for neighborhood parties in South Philadelphia. He chose his first name in honor of his hero, the legendary Robert Houdini. One of Merton’s favorite tricks was guessing what cars his audience owned based on their middle names. It’s reported that Schklonick/Merton was surprised by the way focus groups were adapted by marketers to study consumer behavior, though it seems the inventor of the concept of “unintended consequences” might have predicted this outcome.

Now Christine led me into the back room of the back room, filled with supplies and samples but still had enough space for a quick consult. Christine didn’t chastise me for my ignorance but did feel it was time for a teaching moment. As I’ve tried to suggest, Christine was a hyper-competent, no-nonsense professional on the fast track, a woman I was thrilled to have as my supervisor. It’s also true that Christine possessed the kind of ethereal physical beauty that sometimes made it hard to understand what she was saying when she was saying it. Perhaps accustomed to this problem, Christine now began an off-the-cuff presentation, writing in alternating black and red EXPO dry erase markers on a spare whiteboard she found in the storage room.

1) BRAND’S ARE BUILT ON TRUST

Sensing correctly that I was about to ask her to clarify what she meant by trust, Christine met my eyes with a piercing gaze that communicated she knew about my fancy background and if I was going to start parsing terms, I should reevaluate my career choice right now. She knew I knew perfectly well what she meant.

2) BRANDS WHICH DELIVER A FUNCTIONAL BENEFIT (I.E. CLEAN DISHES) BUILD TRUST WITH PROVEN RESULTS

Here I did succeed in interrupting briefly to mention our client’s well-known commitment to product superiority in every category they entered. Superiority was a pillar of company strategy and required an investment in R&D that, no joke, exceeded the GNP of many developing nations. “Aren’t we always the best?”

Christine nodded, holding my gaze with eyes that seemed to oscillate between teal and lapis lazuli depending on the light. Then, she turned back to the whiteboard, writing quickly and speaking slowly so the writing and speaking were synchronized:

3) SUPERIORITY IS PROVEN IN THE LAB BY MEASURES THAT EXCEED THE ABILITY OF THE NAKED EYE

Christine stood like someone who had trained as a ballerina in her youth, her pelvis pushed slightly forward and shoulders thrown back, especially when she was pausing to think which gave me another opening:

“So,” I said, ‘this ‘superiority’ while defensible in a court of law, is really an epi-phenomenon. It’s the perception of superiority we’re talking about, isn’t it?”

Christine nodded again, acknowledging my point so far as it went. My problem was my distinction between real and perceived benefits. They were one and the same from a marketing POV. But this answer raised another question. Why pour all that money into R & D if belief is the endgame? Christine smiled in a mysterious way. Perhaps she thought this was a cynical observation. A pause hung in the air as she lifted a box of the prototype from the floor The box was the same metallic green of the dishwasher brand we stored under the sink in my childhood kitchen but from it Christine pulled out Randall’s latest breakthrough, a small compact disk, almost organic in its translucent skin containing three different-colored gels. She held it in her open palm. “Do you believe?” I must have nodded because she arched her eyebrows high on her forehead and asked me why.

That was a good question, but before I could answer, the door opened on the storage room and through a narrow gap, the head of Sanjay emerged. From the expression on his face, it was instantly clear that we had a problem–a problem more immediate than the topological expertise of dishwasher-loaders across America.

“Sanjay?” Christine asked as she erased the white board. “Everything, OK?”

“’Fraid, not, Chris,” Sanjay said. “Can I speak frankly?”

Christine nodded, her head tilted slightly in my direction to indicate I was all NDA’d despite my obvious greenness.

“We’ve got a mess on our hands.”

I could see Christine was perplexed. She stepped forward so that Sanjay could relate the situation. In her general resting face, the corners of Christine’s mouth curled slightly upwards, a feature that might look clownish on other faces but on Christine’s created the suggestion that she possessed a secret that anyone would very much like to know. At this moment, however, Christine’s curved lips first flattened out and then continued their downward descent into a face expressing shock and disgust. It appeared that Christine might be sick so fully did her normally tawny hues turn the color of wet concrete.

Christine tilted her head to peer around Sanjay to look into the backroom of the focus group room that looked onto the room itself. I heard Sanjay say that they’d cleared everyone out.

“Where are the respondents?”

“In the lounge,” Sanjay said, “awaiting instructions. Looking ‘bout as anxious as long-tail cats in a room full of rocking chairs.”

“Do they want to leave?”

Sanjay paused and looked down. “We’re in uncharted territory here.”

“And Claire?”

Sanjay looked down and shook his head. “That dog won’t hunt,” he said.

The consequence of Claire M’s indisposition meant a waste of the day’s groups, if not the research as a whole, which I assumed was the reason for the brooding silence that hung over the room. The air darkened, as it does when a lot of money is going to down the drain. Christine’s brow actually furrowed. “I don’t think I need to remind everyone how important this is,” Sanjay added. This was a shift in tone but one that didn’t lighten the burdensome silence which was when I said, “I could do it, I think, in an emergency.”

Both Sanjay and Christine looked at me with different but equally hard-to-read gazes.

“Are you trained?” Sanjay asked

Christine spoke for me, and the answer was quick and clipped and negative.

There was another long pause, during which I and everyone else heard a noise that sounded like retching. All our eyes traveled to the crack in the door, in which Sanjay was still stuck out at a lawn-dartish angle. I wondered if he was having a panic attack.

“You’ve done some teaching? Did I hear that correctly?”

I nodded, but aware of the pressure of Christine’s critical gaze without looking at her, I added, “It’s probably a bad idea.”

All focus group rooms are alike, both to one another and to the endless drop-ceilinged meeting rooms we all spend so many listless hours. My room was one of five in the consumer research center in Columbus, OH . It contained a standard particle-board meeting room table and nine cushioned office chairs. The western wall of the room was devoted to a white board. The northern wall was made up of the large two-way mirror that had been the center of my attention. There was also a ceiling mounted video camera and four microphones set in the table both to record and transmit the proceedings. Everything beyond these basics was imported into the room—including a grab bag of supplies familiar to anyone who has thrown a birthday party for a child: colored markers, scissors, glue sticks, glitter and pipe cleaners and sometimes balloons and Nerf guns all designed to simulate our imaginations and bring the reasons for consumer habits blurred into obscurity by our routines into the full light of day.

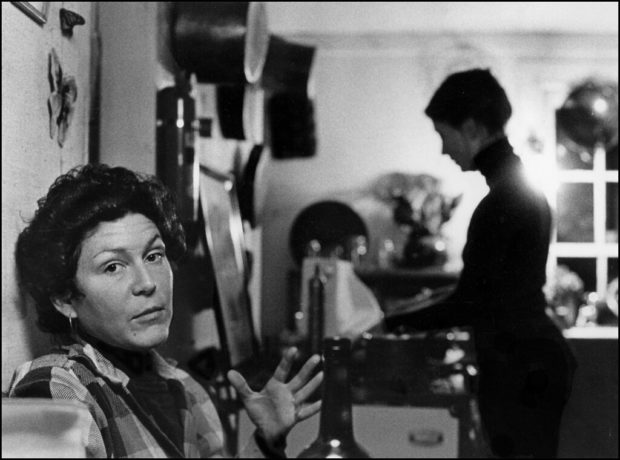

I watched six out of the original eight mothers return to the focus group room with determined hunker down expressions. They settled behind their own nameplates (Dee, Maria, Carol T, Sangeeta, Carol Z, Patti) and over the speakers in the back room, we heard them expressing concern about Claire M, whose own nameplate had been removed. Carol Z said she hoped that she had someone to take care of her because was there anything worse than getting sick on the road? Everyone in the room nodded and murmured assents that there was indeed nothing worse.

“Did she say she was from Washington?” asked Dee.

“The state?” asked Carol Z.

“D.C.,” said Carol T.

“That’s. A. Blessing,” said Maria, each word coming out between slow, open-mouthed breaths. Along with the other mothers, Maria had wrapped her scarf around the lower half of her face. Whether they were shielding themselves from the lingering smell of Claire’s sickness that had been spread far and wide or the industrial cleaners that were applied afterwards, I couldn’t tell from this side of the glass. Dennis Lim’s large head and sharply parted hair jerked back and forth from the watch on his hand to Sanjay to me, suggesting that every minute I stood there was a minute replete with wasted dollars. I took my nameplate from Christine’s hand and headed for the door.

When I entered the room, the mothers looked up at me, their eyes both expectant and anxious above their scarves. I repeated the instructions at the beginning of the session that Merton recommends to build the rapport necessary for an open conversation. There were no right or wrong answers. They would likely disagree. You don’t have to have a rational reason for your opinions. Who among us knows the truth of our own hearts? The mothers looked back at me, smiling politely with their eyes.

The next activity on the list was called STAGES and involved asking the mothers to describe or dramatize their daily routine to bring out the surprising details that hadn’t yet been brought to consciousness. Dee, who had described herself as a “firecracker” in the introductions, volunteered first. Dee wore an Ohio State jersey over a white long-sleeve shirt that went down over her hips. She raised her arm and got right into character: “Thomas, McKensy, Lauren, please get those dishes in the sink right now!”

Dee’s enthusiasm really lifted the energy in the room. Carol T jumped up next and started showing us how she washed the dishes before she put them in the dishwasher which come to think of it, was double washing. What were they washing that couldn’t be washed by the machine? Maria admitted she wasn’t sure. Maria was a big woman with copper color hair. She had the look of a someone who had been through some hard times but wasn’t inclined to complain. Her eyes now took on a reflective gaze. They weren’t really washing because they had to wash.

“It’s more…” Maria began. We all turned to her.

“A habit?” I probed.

“I just love to clean.”

Sangeeta had the brightest scarf of all, saffron-colored and filled with images of blue-skinned gods. She now pulled it from her mouth to say, “Yes,” she said, “This is correct.”

This wasn’t what Randall wanted to hear. His innovation included special enzymes and proteins that would remove this arduous extra step, the unmet need that apparently wasn’t needed. I needed to find a problem, the elusive torture test, a problem that lived on, stubborn, enduring, unresolved. I placed the new prototyped pod in the center the table and we all stared at it for a moment. What did they think it was? What did the colors mean? My questions didn’t seem to register. They dissipated into a new stillness that filled the room.

In his training manual, Merton draws a distinction between two kinds of silences, what he calls “dead silence” and “pregnant silence.” Dead silences are a failure of the moderator. Pregnant silences, however, are full of potential gifts, a sign that hidden impulses were stirring in the silt of our deep coastal shelves. I felt a growing warmth in my face and looked down at the spread sheet where we summarized the mothers’ lives. Children, income, work, attitudes, beliefs, behaviors. Maria’s household income was between 65 and 75k; she worked part time in a flower shop and described herself as “a cleaning freak.” I saw she had three children in the house but in the next question she listed four ages 16, 14, 6, 11. It was then I knew that her third child would be six forever. I didn’t know it in some magical, clairvoyant way but because she told us. I watched as she moved her hand slowly, touching her shoulder then her face fingers in the air. She looked out at me and through the suddenly chill air. I looked around the room. Dee’s eyes opened wide, hands pressed flat to the table. Sangeeta and Carol T both pulled sweaters on. I waved my own hand through the air, fingers spread, as if I was pulling open a curtain. “Thank you,” she said. She wasn’t talking to us. The other mothers in the room nodded, their scarves falling from their mouths. They didn’t seem concerned by whatever was happening, even as Maria’s words slipped into another language, which I thought at first it was Spanish or maybe Portuguese. It didn’t matter to the mothers. They knew sound matters more than sense. As she spoke, she held her hands to the room. The other mothers raised their hands too, as if mesmerized. I can’t claim to have seen or felt anything in the room, except the mothers themselves, now immersed in their own experiences, their lifetimes spent caring for their children.

I heard a thud behind me as if someone had fallen out of a chair and when I looked back, I saw my own face staring back at me, the mirror reflecting and enhancing my dismay. In front and behind me, I saw the room as through a glass darkly, watching as the mothers now join hands in a communion. There was a gathering vibration in the room, the kind that starts when people who know how to pray start to pray together. In the mirrored glass, the light seemed to bend, as if a force was pushing on it from the far side, and in the reflection, I watched the pod in the middle of the table quiver and the gel leak out in a small multi-colored stream, forming bright ectoplasmic pool.

“Oh dear,” Carol T jumped up and reached into the cabinet under the TV where she instinctively knew where the cleaning supplies were stored. The other mothers stood up to help. The sudden activity broke the tension. Maria was still now, leaning back in her chair. Sangeeta removed her scarf and leaned over to wipe away Maria’s tears. “Take your time,” she said. You might think I’ve made this up, but I assure you it’s true. Nor would this be my last visitation. My research would be full of uninvited guests, children seeking comfort, lovers with torn hearts, abandoned husbands, angry fathers, all demanding to be heard, addressed, tended to. Six months later, in a new job, it was a gathering of stepmothers. I was collecting information to help my client portray nontraditional families. The mothers erupted into in a torrent of rage against the fairy tales and films that marked them as invaders, cruel masters, witches. The stepdaughters arrived to demand expatiation, a pound of flesh. Their battles were locked in an iron cage. The next year, it was new mothers. I was exploring changing attitudes about sun tanning. I was working on behalf of a flailing skincare brand, the one with a French name. In the late 70’s, their advertisements contained a lithe bohemian model strolling along beaches on the French Riviera. Over-exposed in grainy shots, the model’s arched brown back blurred into a sensual dream. In the room, the conversation turned to graphic descriptions of sex, passionate assignations on midnight beaches, the taste of salt on skin, hidden hotels filled with lovers’ cries. “I can’t believe I’m telling you this,” they said to me and one another and the camera. In between groups, I splashed cold water on my face, dizzy with lust. Oh, the mothers! They’d be the making of me. Ned, my therapist, agreed. “What would we do without them?” he said, spreading his arms. His office shelves were stacked with the games I played as children. “Tell me about yours,” he said. “My what?” I asked. “Everyone has a mother,” he said.

When I finally went into the back room, the clients had all risen from their seats, the computers glowing idly on the tables arranged around the mirror. Christine was speaking to them in a hushed voice, the kind used by witnesses to a sudden and unpredicted disaster.

“Do I go back in?”

“You can release them,” Christine said, turning to me. “Please thank everyone on behalf of the brand.” I felt the indictment in Christine’s cool stare. I knew I’d made a discovery that day, how brands really work, seeping inexorably into our beings, a source of meaning as enduring as any other—a cross, a flag, a ring. The truth, I learned, was that the actual product didn’t matter. Anything would do. But Christine, Sanjay, Randall didn’t want to hear that. They heard a mockery of their whole enterprise, a global company’s billion-dollar investment turned into a parlor trick. Christine shook her head in dismay. “Think you can handle that?”

The mothers lingered for a long time after the session ended. I had to remind them to gather their checks. I waited in the hall where I saw the manager of the facility trying to catch my eye. He wanted me to check the invoice, worried we might blame him for the earlier mishap. While I ticked off the line items with sounds of satisfaction, he apologized for Claire. She could be sensitive but that was why she was in demand. He asked me if I wanted the videotape now? When I returned to my hotel, I watched it for hours into the night, looking for a shade or shadow, some perturbation in the air. Here’s what I saw: I watched Claire grow silent, her eyes downcast, turned inward, her jaw set. Then her mouth shaped some unvoiced word, her eyes suddenly bulged, and her body convulsed, neck strained, hands clenched to the table before she collapsed. The women all jumped from their seats and rushed to her assistance, mothers to the core. Maria took Claire’s head in her arms, wiping the mess from her face. Sangeeta waved her scarf over Claire’s face. Carol Z grabbed a water bottle while Carol T ran for help. This what mothers were or what we needed them to be, how we made them and were continuing to make them. Now, I watched Maria emerge from the room, arranging her scarf around her neck. I thanked her for her participation. The tears had streaked her mascara and her hair was mottled and lopsided but in her eyes was a serene gaze. She apologized for disturbing the group. I told her not to apologize and offered my condolences for her loss. “You have a gift,” she said, hugging me good-bye.

Christine had another opinion which she expressed at my exit interview two weeks later. I handed her the report which she had requested with a terse email. It was then I noticed another woman sitting quietly in the room, hands folded on her lap. Christine paged through my report as I took a seat.

“What happened in there?”

“Did you watch the tape?” I asked.

“I didn’t have to,” she said.

“We went deep,” I acknowledged.

“Too fucking deep.”

I’d never heard her swear before and felt a little rush of dark energy. “I thought,” I began but Christine spoke over me. She was frustrated they’d invested in my training only to watch me go off the rails. Perhaps they had pushed me too fast. Her mistake, she said, resting a hand over her heart. She took a deep breath and looked out the window. When she turned back, she explained she was sorry, but they could no longer support my role. She let me take this in and then asked if she could give me some advice. I needed to work on what she called professionalism. We worked in service of the brand. We were here to touch lives, she said, quoting our client’s mission statement. So many people depend on us. As I watched, a layer of crimson flushed over her rosy complexion, and her beauty reassembled into a shimmering vale between us. When she finished, she rose briskly and smoothed down her skirt. She wished me luck and left the room to me and the woman in the corner who introduced herself as Angela from HR. Angela was the opposite of Christine in manner and style. There was a weariness to her slow gestures. Perhaps she had troubles of her own or she had developed a convincing performance of empathy. Angela explained the terms of my separation agreement, the particulars of my non-compete and the meaning of a mutual non-disparagement clause. She asked me to sign and initial every page to confirm I had read and understood the terms.

“Any questions?’

“Well,” I admitted

“My advice,” she said. ”Jump right back in there.”

“You think?”

She nodded assertively, walking me to my my desk so I could pack up my things. My former colleagues looked on with uneasy glances. They knew bad news when they saw it.

When I arrived on the street, I called my wife. “Hi,” she said. “Everything ok?” There was a thread of apprehension in her voice. Our new patterns had been established and discontinuities were notable. I told her the news, which was met with ambivalent sympathy. “Oh no,” she said. Then she asked me about severance and whether I was looking for another job.

“This happened five minutes ago.”

“True,” my wife said.

“I’m not worried,” I lied. And in that moment I learned I was being made into something too, someone who needs to believe. It’s not what I hoped I would become but who among us gets to choose? Even Meyer Robert Schlonickoff fell into his profession by accident. He was raised in near poverty by Russian immigrants, a tailor who supported his family with a dairy-product store until it burned down. After high school, Merton won a scholarship to Temple, and then, against all odds, to Harvard to join the emerging field of Sociology. Considering his history, it’s probably no surprise Merton became an expert on the ways we are shaped by forces we neither recognize nor understand. Later in life, Merton admitted his love of magic was the key to his success, unlocking a new way of seeing. There was a paradox at the heart of magic. When we are delighted by a trick, we know we are being deceived, but we want to be deceived. Over time, great magicians do less and less. They know the need for illusion is already in us, universal, unmet, inexhaustible. That’s why we go to the show.

SCOTT KARAMBIS

Scott’s went to The Iowa Writers' Workshop a long time ago. Since then, his work has appeared in GQ, The Quarterly, StoryQuarterly and other quarterlies. Along the way, he won a Mellon, Michener and Teaching/Writing Fellowship but fellowships only last so long and he now works in advertising. Scott currently lives North of Boston with his wife and three children.

- More Posts(1)