You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

It’s a hellish hot night in New York City’s Central Park. You’re crowded into a concert space, the sun setting, the crowd sweating, the album of the summer, the Rolling Stones’ Some Girls (do-do-doo-do, do-de-do, do-do-doo-do, do-de-do) blasting over the PA system. Track after track you’re wondering when the hell Patti Smith is gonna come on and start the show, at the same time you’re thinking, this is the show. The Stones never sounded this good. This loud. This significant. Love and hope and sex and dreams, Mick Jagger sings, does it matter? And here she comes bouncing onto the stage. Black boots, black trousers, black jacket, sleeves rolled up, arms above her head, bouncing and twirling. She gyrates center stage, grabs the mike—“this town,” she shouts, “is all that matters.” And the crowd roars. Then she’s into the show: “I don’t fuck much with the past,” she snarls, “but I fuck plenty with the future.” There’s a clarinet leaning near her bank of amps and a couple of numbers in, she picks it up and starts blowing. Just noise—squeaks, skwonks, squoinks, no relation to what the band’s doing, no relation to song, to harmony, melody, rhythm, and she’s transfixed like a kid on the spectrum. Blowing, screeking, honking. At the edge of stage right, a roadie lifts a sheet of opaque plastic and holds it neck high. She hands off the clarinet, drops behind the plastic and, for the length of time it might take to let loose a good piss she’s just a dark blur in a deep crouch, like a form underwater. Back standing, she buckles her belt, retrieves the clarinet, and the roadie drops the plastic. You’re thinking, did she just piss on-fucking-stage? Did she piss in public? Piss on the hallowed space? You’re thinking “Piss Factory,” that odor rising roses and ammonia. What was she saying, you wonder. There had to be a metaphor, a message. Piss. Performance. Perversion. Subversion.

Your girlfriend says, “You don’t even know if she actually pissed.”

“What else could she have done behind that plastic?”

“Uh, just about every single thing in the world that’s not pissing?”

But you’re not buying it, you insist that she pissed, that you all saw Patti Smith pissing.

“Whatever,” your girlfriend says, “but you’re never gonna know for sure unless you ask her, and even then…”

•••

You feel indebted to Patti Smith. Only a year back you were a sophomore in college, directionless, the veteran of a lot of dead ends and bad mistakes. Detours and detoxes. You’d pissed on stages, as it were, every single one, without the benefit of a plastic curtain. You were beginning to see a way out into the straight world, a way to become a civilian, to participate, to contribute, to wear the pinstripes and carry the briefcase. You visited your folks, told your mother you think it’s going to be law school for you, then maybe politics. She was so relieved, so happy, she started crying, gave you a twenty to go have a beer in town. Handed you the keys to her Volvo. You hit the back roads, put on the FM. From the top pocket of your vest, you fished what you’d sworn would be your final joint, Hawaiian sins, no seeds, all female. You fire up and pedal down and you’re racing along Sound Avenue. You’d know its curves and dips blindfolded and you race it on autopilot, holding deep inhalations, frenching the exhales. On the radio, a program featuring the new noise out of New York: Ramones, the Dolls, Dead Boys, the Contortions. Out of a bludgeoning feedback maelstrom emerges Patti Smith doing The Who’s “My Generation.” Well I don’t need that fuckin’ shit, she shrieks, the hairs on your neck and arms spring up. You envision your law degree on fire and standing over it, Patti Smith pissing gasoline.

•••

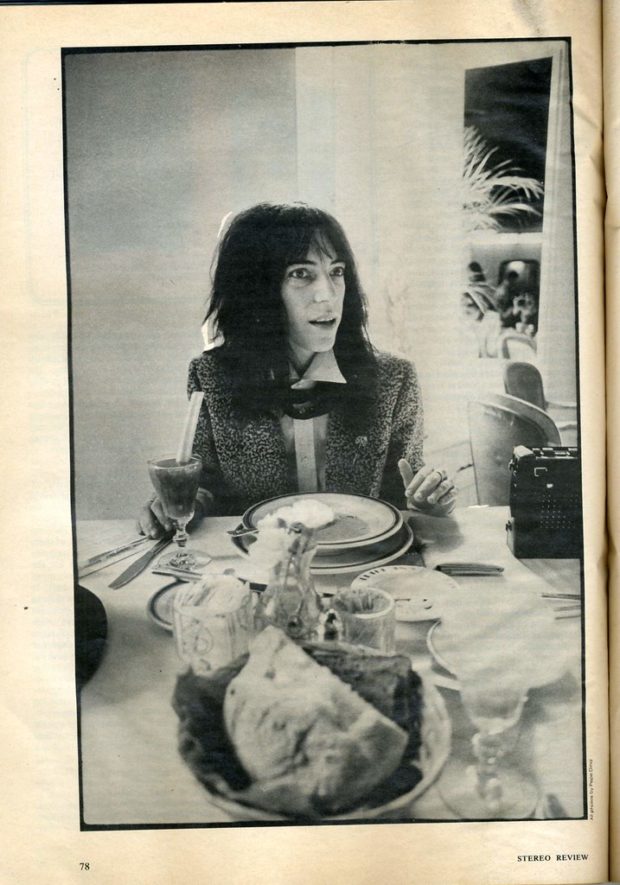

The afternoon following the concert with clarinet, you’re in the Caffé Dante where Patti Smith sits in the window scribbling figures into an unlined notebook. She’s in a Keith Richards t-shirt with an oversized derby pushed back on her head. There’s opera on the PA system, Tchaikovski’s Eugene Onegin. At a tenor aria, her head drops back as if she’d just received an injection. The derby falls to the floor. And on her face, an exqusite pain. She’s wincing at the sublimity, its objective aesthetic beauty, and you’re thinking, this is the woman who sixteen hours earlier was bouncing around with a clarinet like a lunatic in an asylum, and you and five thousand others like you bounced around with her, the canals in your ears experiencing collective paroxysms. When the aria concludes and the orchestra subsides, you get up and retrieve Patti Smith’s hat. Her eyes remain closed, lost in the music. The eyes, lined with kohl, the nose just a bit too large for the narrow face, the perfect bow lips. Slowly the eyes open and they spot you standing alongside her.

“Yeah, kid,” she says, “what?”

You tell her she’s dropped her hat and you extend it.

She says, “I didn’t drop it, man. I didn’t drop it. It fell. Weren’t you watching? Weren’t you listening? Didn’t you hear that fucking beauty?”

You tell her you did.

“Not if you’re policing peoples’ hats, man. Not if you’re policing peoples’ hats. Maybe I wanted that on the floor, at that moment, in that aria, and now you fucked it all up.”

You sputter some attempt at an apology.

“I can’t even understand you, man. Just give me the fucking hat.”

A few minutes later, Patti Smith approaches your table. “Hey man.”

“Ms Smith.”

“Ah, so you know who I am. Getting to be a thing. Listen, something I gotta ask you.”

“Please do.”

“Please do? What are you like from the BBC, please do?”

I blushed.

“Nah, listen, like, back there, I was just fucking with you, man.”

“Not a problem.”

“Man, just listen, OK, let me finish.”

“Please do.”

“There’s that please do again. Listen, I feel bad if you got the wrong impression. See, I’m just…”

You say it’s OK.

“OK with you,” she says. “But what I keep trying to tell you is that it’s not OK”—and here she winds up like a pitcher, reaching way behind herself with her right hand, then coming forward like she’s throwing a fastball, but just at the point of release she spins the hand around and points a finger at herself—“with me, you dig?”

You laugh. You tell her you dig.

She says, “What, I say something funny? Now I’m making you laugh I’m funny?”

You say, “I loved your show last night.”

This stops the schtick.

“You were there? Cool. What was your favorite song, and don’t tell me because the fucking night, I know you’re hipper than that.”

“I liked the clarinet solo.”

She beamed. “Dude.”

She reached forward for a handshake with about sixteen parts.

“How would you describe my playing?”

You think for a moment, then say, “Kind of non-philharmonic crypto-avant dada skronk.”

She looks behind her. “Are we on like fucking candid camera, because that’s the most perfect—listen, what’s your name?”

You tell her.

“Clifford Foote,” she repeats.

“With an ‘e’” you tell her.

“Of course with an ‘e’, man,” she says. “Of course with an e. Otherwise it’s just a fucking foot. And what do you do Clifford Foote with an e. You must be like a poet or something.”

“Film student.”

“What I fucking say? So who’s your thing? Méliès? Cocteau?”

“Cassavetes.”

She says, “Hold on a second.”

She goes to her table, scribbles something on her notepad and rips out the page.

“Here,” she says.

It reads

Clifford FootE

Free Pass for Life, man

“Wait,” she says, “I gotta sign that.”

I spin it around on the table and she scribbles something that is the handwriting equivalent of her clarinet playing.

“For life,” she says, “anywhere I’m playing, you get me?”

Before I can ask her about taking the piss onstage, she’s at the turntable, selects Delibes’ Lakme, returns to her place at the window. At the exquisitely excruciating “Flower Duet,” her eyes squeeze shut, the neck goes slack, the derby floats to the floor. This time, you leave it there.

•••

Her next show is uptown at Hurrah. You show security your pass for life. Security, big and bald with tattooed arms as thick as your legs, laughs in your face.

Then Patti Smith moves to Detroit, the rest of your fucking life happens, and your girlfriend turns out to be right about at least one thing.

Tim Tomlinson

Tim Tomlinson was born in, and has returned to, Brooklyn, NY. In between, he's lived in Boston, New Orleans, Miami, the Bahamas, Shanghai, Florence, London, but mostly Manhattan. He's a high school dropout, a Columbia University graduate, and a co-founder of New York Writers Workshop. He teaches in NYU's Global Liberal Studies. Among his publications are Requiem for the Tree Fort I Set on Fire (poetry), and This is Not Happening to You (short fiction). His poems and stories have appeared in numerous US and international venues, including, most recently, Another Chicago Magazine, Teesta Journal, Quarterly Literary Review Singapore, and Telephone, a multi-media collaborative endeavor including arts from across the globe.

- Web |

- More Posts(1)