You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

By Eric Akoto

The world changed between the initial planning and the delayed completion of this issue.

Beginning in early 2020, Covid-19 spread across the world, becoming a pandemic that has claimed, at the time of writing, over 2.7 million people globally. The two countries with the highest death tolls are the USA, with 554,899 dead, and Brazil, which has an official death toll of more than 292,856. All of these numbers will be higher by the time you read this.

Just as it has exposed the strengths and frailties of global systems, the virus has exposed deeply ingrained historical, societal, and institutional racism. It has disproportionately taken the lives of black and brown people, not least because more of them have been on the frontlines during the pandemic, in hospitals and care homes and as all kinds of key workers. The virus, and the economic hardship that has inevitably followed in its wake, harms poor people, particularly people of colour, far more than the better-off who have much more chances to insulate themselves while benefiting from those on the frontlines who keep services running.

Into this already fraught period came further upheavals. On May 25, 2020, the world witnessed, at the hands of four Minneapolis police officers – under the knee of one of them – the brutal, horrifying murder of George Floyd. Such atrocities are not new, but a wave of outraged protests and marches unlike any that had gone before erupted across many US cities, defying bans on mass gatherings, shouting clearly Black Lives Matter! Ever since those horrifying scenes of police brutality against an unarmed black man went viral, Americans in every state, from small towns to major cities, have been gathering and marching to protest state-based violence against black people. In March 2021, it was announced that the city of Minneapolis would settle a lawsuit with George Floyd’s family for $27 million (£19 million). The trial of the police officer accused of killing Floyd is set to begin at the end of March.*

The Black Lives Matter protests have not stopped at the doors of these states. They’ve taken place across Europe and as far away as New Zealand and Japan, with protesters showing solidarity, drawing parallels to racist violence in their own countries, and highlighting the struggle to dismantle the racist present and the racist past – as in Bristol, England, when the statue of a slave-trader was rightfully torn down and thrown into the river. This is the biggest global collective demonstration of civil unrest in reaction to state-based violence in our generation’s memory. And it is no overnight occurrence – remember Trayvon Martin in 2012, who was killed by Florida police as he walked home from a convenience store carrying iced tea and Skittles. His death and the lack of accountability were catalysts of the movement, which was formed with the hashtag #BlackLivesMatter in protest of his killer’s acquittal. There is a sense that the unifying theme, for the first time in America’s history, and globally, is that black lives matter at last. Things have to change, and perhaps this can be a long, long overdue reckoning with the past and present, a genuine turning point. With Joseph R. Biden’s election to the US presidency, it is hoped that real reform of American institutions is possible after a four-year period which saw white supremacy condoned from the highest echelons of American power.

The protests were given further impetus by last year’s US Open winner (and 2021 Australian Open winner), the black Japanese tennis sensation, 23-year-old Naomi Osaka. Winning grand slams is nothing new for Osaka; it’s her activism on and off the court that distinguishes her, and the face masks she’s worn while playing during the pandemic record a tragic litany of black and brown American men, women, and children who have been killed by police. Osaka’s first-round match of the US Open saw her wear a mask honouring Breonna Taylor, a black woman killed by police officers who burst into her apartment in March 2020. For her second match, she stepped into the Arthur Ashe Stadium wearing a mask that read Elijah McClain, the name of a 23-year-old massage therapist who was stopped by three officers in the Denver suburb of Aurora in August 2019 as he was walking home from a convenience store with an iced tea. He died in police custody after being put into a carotid hold, which restricts blood flow to the brain. Osaka wore Ahmaud Arbery’s name on her face mask as she walked out for her third- round match against Marta Kostyuk. Arbery, a 25-year-old unarmed black man, died of shotgun wounds after he was chased by two white men while jogging in Brunswick, Georgia. In her fourth-round match, Osaka honoured Trayvon Martin, and she would defeat her quarter-final opponent honouring the death of George Floyd. In her semifinal appearance, Osaka honoured Philando Castile, who was fatally shot in July 2016 by a Minnesota police officer during a traffic stop. Osaka recovered from losing the first set to claim her second US Open championship while wearing a mask bearing the name of Tamir Rice, a 12-year-old boy who was killed by police gunfire in November 2014 in Cleveland, Ohio, while he was holding a toy replica pistol.

So, as we turn our pages to Japan, Naomi Osaka we salute you!

*The police officer was found guilty of three charges – second-degree murder, third-degree murder, and manslaughter – on April 21, 2021.

Guest Editors’ Letter

By Naoko Mabon and Kyoko Yoshida

Reportedly, today Japan consists of over 6,800 islands (1). At a time of change and crisis, how can we see and write about Japan? Is it still as golden as Marco Polo described and imagined? Is it a land that goes beyond “Sushi,” “Manga,” or “Geisha”? In which direction is each island of Japan drifting?

We started planning this special issue at the end of 2019. It almost feels that 2019 was a totally different era compared to where we are today at the end of 2020. Not only taking away a colossal number of lives and livelihoods, coronavirus has caused postponements and cancellations of numerous events across the world, including the Tokyo 2020 Olympic and Paralympic Games. Not knowing the new dates yet, Japan has lost a central driving force to reconstruct its unified national imaginary once again, after the 1964 Olympics showed the world Japan’s miraculous recovery from the ashes of the World War II. Instead, pre-existing weaknesses, gaps and corrosions that the country has been suffering for the past twenty-five years have come to the surface.

At the same time, we are still in an ongoing crisis of global warming, racial and gender inequality, and many other critical social issues, such as how to deal with radioactive waste and – as Yoshiro Sakamoto’s essay mentions – how to tackle marine pollution from plastics. The pandemic has forced us to rethink our way of living – how we once were, and how we can possibly be now and hereafter, as one of many living organisms on earth.

In this issue, we have a truly amazing lineup of contributors to respond to the issues that we face in the context of Japan today. They span different locations, fields of profession, and cultures, reflecting the complex societal ecology of this small island nation. Although most of the contributions were written or prepared before the pandemic, together with you, the readers, we hope to collectively imagine an alternative map of the drifting islands today.

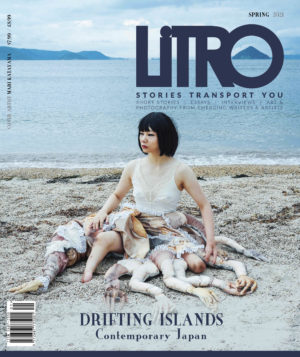

The cover artist is Mari Katayama. Katayama is known for self-portrait photography created with hand-sewn objects and decorated prostheses. She uses her own body as a living sculpture. Born with a rare congenital disorder, Katayama chose when she was nine years old to have both of her legs amputated. On the cover, Katayama is sitting on a beach wearing a soft object with many arms and hands as if they were part of her own body. This was one of the artistic outcomes of her 2016 residency on Naoshima island in the Seto Inland Sea, which is also pictured in the essay by Pico Iyer. Katayama photographed the hands of members of Naoshima Onna Bunraku, a traditional puppet theatre performed exclusively by women from the Naoshima region, printed them onto material, and sewed them into a multi-armed soft sculptural object. In later pages, you can read Naoko’s interview with Mari.

While Mari was inspired by bunraku puppeteers’ bodies and hands back in 2016, throughout 2020, we have been experiencing the absence of physicality and human warmth as well as the limitation of locomotions under lockdowns and the new social-distancing normality. Many of us now spend lots of time at home and most of our social activities happen in virtual realms within our domestic environment. A domestic space – this ambiguous realm can be a bounded area of safety and freedom one day, and a walled cage or prison the next. Yet, it is still a location for us to receive visits from outside world – whether scheduled or unexpected.

Kyoko’s Poetry Dispatch (www.kyokoyoshida.net/archives/219) has started to respond to this period of isolation and lack of anything we can physically touch and hold in our hands. It is a series of small handmade booklets of poems, which she randomly posts to her friends’ home addresses. It is a little, surprising visit. Like birds and small animals living on the canal in neighbourhoods, venturing out of their former territories and ending up napping on our doorstep. These visitors cannot replace our families’ and friends’ visits, so they remind us of our isolation and may even intensify our loneliness, but they are all the more precious because they reveal that this loneliness connects us.

We hope our Drifting Islands issue finds its way to visit to your home – ideally physically but even virtually – so that it can connect us over distance while your hands or eyes travel through each page.

Last but not least, we send our deepest gratitude to all the writers, translators and artists who joined our endeavour to shape this Drifting Islands issue. We also thank Editor-in-Chief & Art Director Eric Akoto, as well as the team at Litro, particularly Assistant Editor Barney Walsh and Designer Brigita Butvila, for inviting us to join such a special opportunity.

(1) Islands with a perimeter longer than 100m at high tide. Based on the information published in 1987 by the Japan Coast Guard.

Note: In accordance with Japanese custom, in several works in this issue the family name is given first.