You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

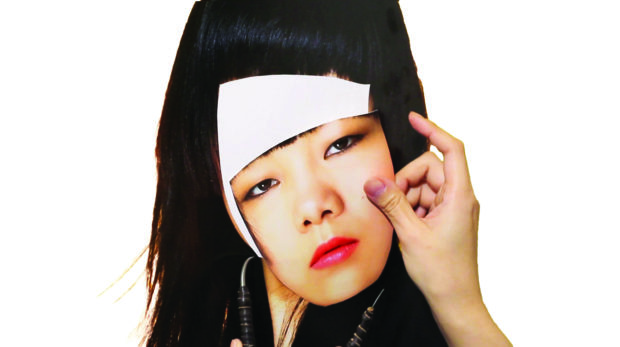

Courtesy of Akio Nagasawa Gallery

Naoko Mabon: Mari, thank you for giving up your time for this interview today.

Mari Katayama: Thank you very much too.

Mabon: Thank you also for agreeing to come on board for shaping Litro’s World Series together with us. It is really exciting to have your work for the cover of our Drifting Islands issue. Especially this particular piece from your bystander series, which was developed during a residency in Naoshima in 2016. In the piece, you seem to have just landed on the Naoshima beach, in front of the beautiful backdrop of the Seto Inland Seascape, with the little pointy Ozuchi island floating at the top right, and The Great Seto Bridge connecting Okayama and Kagawa prefectures in the distance. At first glance, the image seems merely beautiful, but there is more to it than that. In the photograph, your facial expression doesn’t seem to be completely happy yet you hold strong eyes, while your upper posture is upright as if indicating a tension or firm will within you. As this body language may suggest, Naoshima, although it is now known to the world as “Japan’s art island”, had suffered from air pollution by smoke from a copper smelter, as well as a shrinking and aging population. On Teshima, another island within the same Naoshima island chain, for a long time there had been the largest legal case in the country about the disposal of industrial waste. Thinking of the relation to and the direction of the theme of Drifting Islands, we therefore thought this image is the perfect face for our issue.

Here I would like to ask you a few questions relating to the work, so that this interview will naturally become an introduction of you and your practice to the readership of Litro Magazine, which is not necessarily exclusive to a contemporary visual art audience.

One of the factors that makes the bystander series stand out – possibly a turning point – in your artistic trajectory is that this is the first time you feature bodies that are not your own in your photographs or work. Up until this series, mostly you alone had been creating self-portrait photography amongst a flood of embroidered objects and decorated prosthesis in your personal space. I recall you mentioned that, even though you gained a result you never achieved on your own in the end, you were a little scared by and took some time to understand and accept the shift. Can you tell us about this shift in the dynamics between yourself and others, and the impact that it has brought?

Katayama: In recent years, there have been gradually more and more things that I cannot do myself. Parenting is one example. So the shift, I think, is a positive consequence of my sort of surrender to things that I cannot do on my own. The topic jumps a little, but since I was little, I had been the kind of person who gives things up quite easily. I was really into Manga, illustration or fashion in the past, but gave all of these up in my teens. I thought “I don’t think I can become a Manga artist or an illustrator. I don’t think I have a standout sense of fashion,” so I quit. When you make a clean break like that, I think you can move on and concentrate more on the next thing. If I still made Manga or illustration, perhaps I wouldn’t have achieved what I create now. Giving up something leads us to the next thing. For me, this is one of the positive actions.

Until about 2016, “do everything myself” was my motto. I set a rule, to always release the shutter myself, which at the same time constrains me. That rule is still valid today. But I realised around the time of working on Naoshima that I cannot live without asking someone for help on other things. The more occasions I had to go out from home and engage with communities and people in the outside world, the more I felt that I lived within a web of human-made society and within the limit of what one person can do. So the shift has occurred alongside the art-making process. Ah, but wait. Maybe because I felt like that in my daily life, then the art-making process might have changed accordingly to asking for a hand from others. Or maybe this has happened simultaneously in both life and work.

At the beginning of the residency programme on Naoshima, I was thinking I should make something to do with Naoshima. At the same time, I really didn’t want to disturb the people of Naoshima with what I will make. Naoshima has been characterised as the “art island” of Japan. However, I think that just coming in from somewhere else and disturbing the beautiful rules and rhythms of the local life there is not an artist’s privilege, it is just blasphemy. I really wanted to avoid that. So I focused on the approach of “borrowing” and “listening to their stories”. The overall project took a whole year to complete. I think the first visit was in Autumn 2015. To begin with, I was given an introductory lecture on the Setouchi region and Naoshima. After that, I visited Naoshima about ten times altogether. One week stay for each visit. I took a long time for research too, over one month. Then it gradually became apparent that the society and lives of people here are, in many aspects, tightly interconnected. The scale of my project became bigger and bigger at the same time. It felt like a circle of people holding each other’s hands, which got bigger and bigger.

Mabon: Another significant point of this bystander series, I think, is your source of inspiration, Naoshima Onna Bunraku, which is likely the only Bunraku company in Japan run exclusively by women. Seemingly there were two main points that you found striking when you visited them. First was seeing them saying how important it is to remove your own existence as a puppeteer, by wearing all black while performing. And second was seeing the importance and versatile ability of the puppeteers’ hands. Sorry for this long question, but could you tell us a little bit about your experience with the group?

Katayama: This might repeat what I said, but I put extra care into what I do on Naoshima because I wanted to avoid becoming an artist who just comes into a particular local culture, creates disturbance, and leaves. I spent much time on research and listening to stories. However, I was not accepted at all, in the beginning. Before my first visit, I told my rough ideas, such as “hands” and “dolls”, to the coordinator of the host organisation. She told me that Naoshima’s Bunraku puppet dolls are quite large, but have no legs. Puppeteers’ hands are a substitute for legs. Normally three puppeteers hold one doll. For instance, they put their elbows into the doll’s Kimono to represent the knees of the doll. Another person will make noise with their hands to express the sounds of steps. Some dolls have legs but mostly they are operated like that, she told me.

When I first visited the company, as an introduction of myself and what I do, I showed them pictures of the latest series at the time, shadow puppet, and explained that the concept of this series is the versatile characteristic of hands – they function in many ways, they can be anything, they can break and recreate at the same time. But it wasn’t received so well and somehow made them feel that I might misinterpret their well-established Bunraku dolls and use them carelessly. Actually, I took quite a lot of photographs of the faces of Bunraku dolls while I was researching. Since they have many dolls, the company members were saying that pictures of the faces would be very useful when they sort out the archival material of each doll. So I took photographs to help them. But I didn’t use those doll-face pictures for my new work. Instead, I asked if I can photograph the puppeteers’ hands. The relationship with them never became bad, but we built a relationship while sometimes probing each other, sometimes doubting each other.

Naoshima is now known as an art island, and so the locals have had various experiences of art. Many have good feelings about art but when there are supporters, this means that there are opponents too. It is obvious but it gave me, as an artist, a very important influence. I think this recognition has also influenced my artistic production and activity. The recognition towards the fact that society is not only composed of a good side. When there is a good side, there is always a bad side. I have built my communication with the members of Naoshima Onna Bunraku, and in the end they have supported me tremendously. At the opening of my exhibition, they came with Bunraku dolls and opened Kusudama (the decorative paper balls to open at celebratory occasions) with the dolls. In the end, we became very close. I spent almost every day with locals. We still exchange emails.

Mabon: As this Litro World Series is focusing on contemporary Japan, I wanted to ask about your view of Japan. For a long time while working as an artist, for instance from your High Heel project to your series on Naoshima or the Ashio copper mine, I feel that you have come across many aspects of the country such as histories, systems and future hopes. Also, last January, you had your first solo exhibition outside of Japan, at the White Rainbow gallery in London, and later at the Venice Biennale in Italy, and a solo exhibition at University of Michigan Museum of Art in the USA. I myself feel that once you step out of a situation, you see it better. And as you work more often outside of your country of origin, I wonder if you now think about Japan more often or see your background better. This is another broad question I am afraid, but can you tell us a little bit about your view towards Japan?

Katayama: Hmm, it’s not an easy question to answer… I lately think “But then, why am I still here?” The negative feeling towards Japan is growing, yet I am still here, in Kunisada in Gunma. It is not that I like Japan. Instead, how do I say, I think this place just suits me. It is possible that there are other places in the world that could also suit me, but when I think of my living pattern right now and of my family, living here is after all the most comfortable choice. Indeed there are many things in politics and cultural affairs that disappoint us in Japan. In terms of culture, I recently feel that artwork cannot become artwork in this country, probably because art professionals such as artists and people who value artworks are not cared for properly.

For example, even if an artist claims this cup is an artwork, the cup cannot become an artwork without professionals who are able to judge its worth, such as curators or critics. But I think there is a tendency that the country is only trying to protect works that have been already established and valued by someone else. This is seen not only in the contemporary art world, but also in arts and culture in general. There is no collectiveness growing amongst artists who work overseas, for instance. There is no occasion to share our experiences or information of the overseas art world, which means there is no discussion on how we can keep going as artists. It is actually a little doubtful whether Japan is a country where artists who gain experience overseas would like to come back to. So, when thinking of my daughter’s future, I sometimes wonder whether we should go somewhere abroad for her. Indeed, the more I have a chance to go and work overseas, the more I think about Japan. But definitely not optimistically.

Mabon: Although Litro features visual elements such as photography and comics, it is primarily a creative platform for literature such as short stories and poems. I wonder if we could ask about your relationship with literature – either reading or writing – such as novels, creative writings or poems?

Katayama: First of all, about words. I hadn’t really trusted the power of words. When we say “apple”, one person might imagine a red apple, the other might think of a blue apple, while another imagines a green apple. The words are so loaded. There is a level when you say “happy”. It may be a lie when you say “happy”. I was therefore believing that, as soon as you turn your feelings into words, they become all lies. This belief had made me only have small, unimportant talk when I have conversations with friends. Of course I speak more properly in an interview like this. But when I speak with friends, I could make funny stories without any problem, but was scared to tell them my opinion or thoughts. I didn’t really believe in the power of words like that. But nowadays I recognise that people don’t get what you are trying to say if you don’t clearly tell it to them. Nothing new really, but people don’t know until you say “yes” or “no”. This realisation is very much related to the fact that I became a mother. To make things easy to understand for my daughter, how can I say? When she asks “why”, what is the clearest explanation to use? I now spend more time on choosing my words for her, and this is gradually making me trust words.

Last year, I had a talk event with the novelist Keiichiro Hirano and read his novels. They are so wonderful. I first read Artificial Love (2010), and At the End of the Matinee (2016). I read his essays too. They are novels, but I just got surprised to see how much you can describe what you think. This is just what I felt, but I was astonished by the power of words. To me, books had been objects I used to collect information. I am otaku (geek), you see. Rather than reading literature or culture and arts, to me it is more for information. Same with music, I listen to music to check it out and get new information. So I had almost never really appreciated novels or texts in a way like appreciating a favourite painting or a particular pianist of classical music. But lately, I have more moments of learning, for instance through Hirano-san’s amazing works and how to deal with words for my daughter. This led me to write texts myself. I have just finished writing a text looking back at the last five years of my artistic journey.

Mabon: I read the text, and somehow imagined that you must be someone who has been reading constantly since you were little.

Katayama: In my opinion, we can only say “I listen to the music”, when we have followed the sounds of all the instrumentals involved. Same with books. I think we can only say we’ve read a book when we have memorised the lines of characters in the story. So in terms of quantity, I have indeed read so much so far, but I don’t know if I can say that I have properly read them, or like them. This is because once I realise that I like it, I read it so many times, like thirty times. Lately I am obsessed with a series of Manga called I Want To Hold Aono-kun So Badly I Could Die by Umi Shiina (2016–), and oh my goodness, how many times have I read it, definitely more than thirty times. Before going to sleep, I usually read from volume one to six. And before I know it, it’s something like three in the morning (laugh). I am so excited to read volume seven and when I think of it, it makes me almost unable to sleep. But recently my interest is gradually shifting to Fargo (2014–). It is a TV drama series based on the film directed by the Coen brothers. The series hasn’t started recently, but I started watching lately and now can’t stop. I watch one season, and usually watch the same season again before moving to the next. Similar with novels. I usually read three or four novels simultaneously.

Mabon: Goodness, that sounds impossible!

Katayama: I suppose I am such an otaku. When I focus on reading only one book, I get bored. So when I read, I read this, and this, and this, something like that. But once I got drawn into it, I read the same book all the time, over and over. Same with music. When I read a book to collect words as data, I read as if I am taking photographs. It is like picking those words by photographing them in high-speed. Music is similar. I memorise a song through my throat. My throat remembers the melody so I can sing instantly. The lyrics are remembered by the throat too. I recall what the song says by singing, because lyrics first come into my ear and are memorised through my throat. Rather than thinking in my head and singing, it is like converting what you heard through the throat into words. Maybe this is not so ordinary. For example, my husband, who is a DJ (HIROAKI WATANABE aka PSYCHOGEM), says he can’t identify the lyrics here. Indeed it is incomprehensible when I hear or think in my head. But once I sing, I know it. It might be the same with words.

Mabon: Maybe words don’t go through your brain. Sounds more like the words go through your body.

Katayama: Yes, perhaps. I recall the scenes described in a book in my head. Making installation plans for exhibitions too. When I make a plan, while walking in an empty exhibition venue, I input the images of the venue in my head first. Then back in home, while looking at the photographs I took in the venue on my computer, the reproduction of what I saw in the venue will be built in my head as a 3D imagination.

Mabon: Composing it in a physical manner.

Katayama: Yes, I think so. That is why, when someone says please place this work on the right, I become confused. Something like which side should be on my back?! It is confusing because I am always in my 3D imagination myself. Maybe this is the same as when I read a book. Words and body are so intimate. Like how I learn song through my throat.

Mabon: Were you writing lyrics when you were a singer?

Katayama: Yes, I was. When I was in a band. In bands, usually there are two types of people. One type comes from music, and the other comes from words. Music types would say “No, we cannot fit four words here” (laughs). For example, when we want to say spring, summer, autumn, winter, there is a moment when the music type can say “We need to cut winter”. Even though you complain “No way, it will become three seasons rather than four and it will change the whole context”, sometimes it is fine for the music type. It is not the reason of course, but band activity didn’t quite work out for me so well, and I quite quickly gave up.

Mabon: So you are more the word type person?

Katayama: Yes, I suppose so.

Mabon: Last question. Do you have anything that you forgot to mention or you would like to say here? Also, if you could tell us a little bit about your ongoing or future plans and developments, that would be great.

Katayama: I am planning to release a debut music CD this year. I know that I just said I gave up on music, but I like music after all. When I was seriously making music in the past, I always felt that I was half-baked. My husband is a music professional, and we have been talking about doing something together for a while, so it just became more realistic in these days. Another intention is that I just simply love what he creates. I just want to make the most comfortable environment for him and his creation. If we can do something together, even better. We just made a club event SPHERE together in Takasaki in Gunma, but we wouldn’t like to limit the locations or situations for the activities. But also, I guess that I am responding to a physical urgency. Within our bodies, it is quite obvious to us when we can do something only now. So I thought maybe quicker action is better, and I am now thinking to try to focus on music-related activity for next ten years. The experience there will definitely become an influence for my visual art activity, so I think that having periods for different activities may not be a bad idea at all. I do what I would like to do, while continuing to work on art on one side. I believe that both creative activities – music and art – are connected. Maybe vinyl is better than CD, actually? Yes, vinyl it is!

Mabon: That’s all for now. Mari, thank you very much indeed for your time. It was such a pleasure to be able to talk with you and hear more of your in-depth stories and thoughts, beyond what we can see through the finished artwork. Thank you so much!

Katayama: Thank you very much!

According to one Japanese-English dictionary, “bystander” can also indicate “Waki”, the supporting role in a traditional Noh play. There are some rules for Waki: it is an opposite role to Shi’te, the principal role; and Waki never wears Omote, the mask. Shi’te wear masks most of the time, as they often play phantom characters such as gods, spirits, vengeful ghosts and ogres. On the other hand, Waki don’t wear masks because they are usually illustrated as characters living in real life. Hence Waki is an existence standing on the same side as the audience, which acts as a mediator connecting the audience to the separate world created on the stage. Similar to the female puppeteers of Naoshima Onna Bunraku, wearing all black to try to be invisible, Mari Katayama is also someone who, while putting herself a little aside, is devoted to play the role of “bystander” mediating in between us, the viewers, and her creative world – no matter whether in the form of visual art, music or written, spoken or sung words. The conversation with Mari was provocative – and now I can’t wait to listen to their new record!