You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

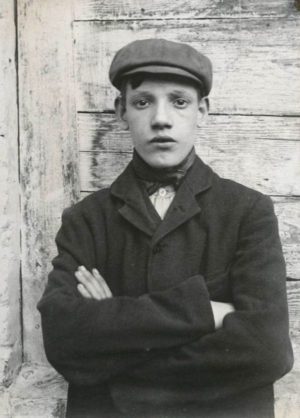

Stephen Andrews stole fifty three-penny sweets from the corner shop. Stephen Andrews ran naked across our road. Stephen Andrews right-hooked his back-from-prison dad. Stephen Andrews only had one kidney.

He left one day without warning, his empty chair pushed too far under his doodle-covered school desk. Nothing for a month and then he rang, sniffling on the end of the line, telling me his mum had taken them up north and he was going to donate his right kidney to Jeremy, his straw-haired brother.

*

Years later, tagging along with my sister, hoping one of her friends would cop off with me in the filthy corner of Parana’s Bar and Bistro, Stephen Andrews wobbled over with a shot of something amber in one hand, an unlit cigarette in the other. His skin, once chalk smooth, was now acne-scarred. Tufts of brown hair sprouted brown like sun-withered weeds from his chin. The old lines were drawn when he didn’t speak. Half a pint later, I said: “Recognize me?”

When he spoke, parched lips flattened against the rim of the glass — one jerk of his neck draining it dry — the words came out sharpened by the spirit. “Borrow me some money, would you, Stump?”

Stephen Andrews got straight F’s. Stephen Andrews got drunk in French. Stephen Andrews fingered Karen Hazard in the boys’ toilets. Stephen Andrews would rest his bumfluff chin on my prickly head and call me “Stump.”

Halfway between the cashpoint and the Odeon Cinema — one hundred pounds gleaned from yours truly with a hands-in-prayer promise to pay me back — trouble kicked off as we passed a group of lads. Stephen Andrews spinning around yelled: “Take all you cunts on!”

“Take all us on, is it?” said the red-eyed leader of the gaggle or pride or murder or whatever you call a collective of chest-beaters in T-shirts. He had me by the ear like an end-of-tether teacher.

“His words,” I said. “Not mine.”

Stephen Andrews could do zero to “really fast,” quicker than me. Stephen Andrews owes me a new set of front teeth. Stephen Andrews took my pouting sister behind some bins while I played with a shard of broken bone in my nose.

*

Such a strong grip for a nine-year-old, Tyson leads me to the candle flame. “How long can you keep it in for, Uncle?”

I try to keep my finger in the flame longer than Tyson, but the smell of burning flesh gets right up my nose.

“True, is it you lost your front teeth helping my dad?”

Tyson’s never-met dad had much to answer for.

*

Stephen Andrews has been spotted on the Costa del Sol. Stephen Andrews has been spotted in Sofia. Stephen Andrews has been spotted high up in the Atlas Mountains. Stephen Andrews has been spotted in Burnham-on-Sea.

It’s a thirty-minute bus ride to Burnham-on-Sea. I stagger down the promenade with a newspaper shielding me from the pelting rain. The front page of the sodden local rag has a picture of an older, thinner Stephen Andrews beneath the headline: “Kidney Cancer Lottery Winner Won’t Quit.”

Stephen Andrews’ brother died when he was eight. Stephen Andrews only has one kidney. Stephen Andrews has a sad story. The first two are straight from the horse’s mouth. The third’s my take.

A thin roll-up between purple lips, Stephen Andrews cuts a scrawny figure behind the beer-sticky counter of The King’s Head. He polishes the same beer glass until it squeaks.

“How’s the sprog, Stump?”

“Like you.”

“His mum?”

“Better without you.” I paused. The glass squeaked. “How much you got?”

“Months.”

“I mean money.”

“Too much.”

I keep my tongue rolled like a fat cigar behind my false front teeth.

I unfurled the damp newspaper. “I guess, ‘Won’t Quit’, refers to you serving pints until you drop.”

“Today’s a good day.” Stephen Andrews points at a full head of hair above his wan face. He tells me it’s a wig then stops and holds his index finger up like that guy in the painting of Jesus having supper. “You can still smell Karen Hazard on that.”

On his gravestone, I’ve installed an artificial candle and a bunch of top-notch plastic pansies.

Stephen Andrews left lottery millions to “you and yours” — his words, not mine. Stephen Andrews paid me interest for the hundred pounds lent way back — my words not his. Stephen Andrews’ epitaph reads:

Stephen Andrews

Father, Son, Brother, Friend.

Cunt.

His words, not mine.

Paul Attmere

Paul Attmere is an actor and writer. Originally from the UK he now lives with his family in Krakes, a small town in Lithuania. A graduate of Goldsmiths University, London, he's been published in Spread the Word - Flight Journal, Running Wild Press Short Story Anthology, The Disappointed Housewife, Literati Magazine, and Sixfold Anthology.

- Web |

- More Posts(1)