You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

An award-winning author, Norman Erikson Pasaribu is part of a tradition of queer Catholic writers, who challenge heterosexual traditions and constrictions in an attempt to open up his work to alternative – and more inclusive – perspectives. Merging his Christian heritage with his Batak cultural background, he questions binary gender roles and subverts stereotypes. It may be relevant to his work that there are five genders in Bugis society.

Pasaribu is one of the most important Indonesian writers today. His first poetry collection, Sergius seeks Bacchus, won the PEN award in 2018 and he was awarded the Young Author Award by the South East Asia Literary Council in 2017. In his work, religion and sexuality intersect in a working-class environment, in which single mothers fight daily to raise their children. Fathers are dead or absent and the children feel abandoned and isolated from the rest of the community. In this context gay characters are very visible, but they are also criticised and sometimes bullied and ostracised and with nobody caring about them, they fade into the shadows. Resisting the idea of being ignored and consequently erased is constantly present in Pasaribu’s narratives. He defies conventions in a shape-shifting, playful way that has dramatic undertones.

The title sets the ambivalent tone of the short story collection, where “mostly” is the translation of hampir, the Indonesian word for almost, which is similar to vampir, vampire. As Pasaribu remarks in an interview with translator Tiffany Tsao, “[W]e queer are always thrown to the hampir, to the almost, and there the idea of happiness turns into the vampir.” There is a constant yearning to be accepted by family, society and friends, who, even if they appear to be making efforts to embrace queer people, rarely accept them completely.

The stories are also connected to Simone Weil’s writing and her concept of decreation, that is, an undoing of the being who gives themselves up to God. It is a mystical union that empties the self and, at the same time, liberates new energies, transforming the individual. It is a progression that uproots all certainties and social roles, in an operation of reversal that is intended to be a total conversion. Weil’s concept is developed in a more contingent way in Pasaribu’s work. Though the connections to Christianity and the Bible are very present, and often parodied, God is absent as a healing and loving force. Biblical stories mix with other narratives, such as those in Toy Story 3 and in Joni Mitchell’s songs, failing to provide salvation or redemption. God is one of the options available, but He does not solve the problems of loneliness, inadequacy, and eventually loss that the different characters suffer. And, ultimately, it is this condition of permanent exile that affords a flexible view which is unsettling but also enriching. The twelve stories in the collection refer to each other both in the developments of the plots and in the building of the characters whose destinies seem to intersect. Absences, pitfalls, and a quest for love and acceptance are emphasised in the course of the narration:

And so, from that point on, in order to make the story even sadder, I decided to start taking Writing classes—where questions like “What is the worst thing you’ve ever experienced?” and “What is your darkest secret?” are routinely trotted out to be answered by people, a portion of whom are sure from the start that it is they who have the most miserable experience, the strangest secret, the wildest imagination, to the point that, from the start, they won’t take much interest in the story I’ll tell them, much less in me. (“A Bedtime Story for Your Long Sleep”)

Resilience and survival in poor, rough environments are recurring themes, together with the additional stigma of coming out as gay in a society dominated by heterosexuality. Single mothers not only struggle to raise their children but also have problems accepting their gay sons: “This is my son,” Mama Sandra told the woman in English, pointing to the turtle in the glass case, tears streaming down her face. “This is my son.” She felt the woman would understand somehow. “This is my son, you know.” (“So What’s your Name, Sandra?”)

For this reason, the mothers’ emotional struggles mix guilty feelings with love for their sons. They seem unable to “decreate” themselves and open up to different possibilities. The vulnerability of relationships between siblings, and even between parents and their children, is often devastating. Jealousies and misunderstandings displace lives and trigger suffering, all of which is emotionally described in these stories. Feelings overflow in a poetic language that is moving and involving. The characters move in a maze, in a surreal atmosphere that reflects our reality, looking for a place to rest:

Six months ago, Sister Tula was sent to the retired nuns’ convent in Pondok Aren. Now, she has started sneaking out. She heads to a shopping plaza, carrying a change of clothes—a T-shirt and long skirt. She stops at every shop, contemplating everything she doesn’t need or can’t afford. The gleam of wristwatches. The scent of imitation perfume. The colorful stained-glass plates and cups. Until the day comes when none of them can move her heart anymore. The only one in this wicked world who can complete me is God. This was what Tula told her boyfriend, Anton, forty-five years ago. I guess even God needs His nuns young. This was what Sister Laura remarked bitterly to Tula on their first night as roommates. Not like us. (“Ad Maiorem Dei Gloriam”)

All places, however, offer only temporary shelter, and all relationships are unreliable, doomed to change or expire. Possible endings are therefore open to further developments that can be better or worse than what we are currently experiencing. This being in flux seems to be a characteristic of humanity that opposes fixed social roles. The stories in the collection trace this journey deftly and with expertise.

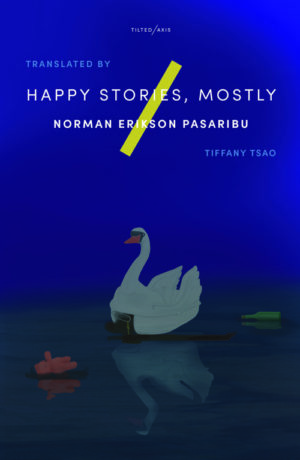

Happy Stories, Mostly

by Norman Erikson Pasaribu

Translated from the Indonesian by Tiffany Tsao

Tilted Axis Press, 173 pages

Carla Scarano D'Antonio

Carla Scarano D’Antonio lives in Surrey with her family. She has a degree in Foreign Languages and Literature and a degree in Italian Language and Literature from the University of Rome, La Sapienza. She obtained her Degree of Master of Arts in Creative Writing at Lancaster University in 2012. She has published her creative work in various magazines and reviews. Her short collection, Negotiating Caponata, was published in July 2020. She and Keith Lander won the first prize of the Dryden Translation Competition 2016 with translations of Eugenio Montale’s poems. She completed her PhD degree on Margaret Atwood’s work at the University of Reading and graduated in April 2021.

- Web |

- More Posts(2)