You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

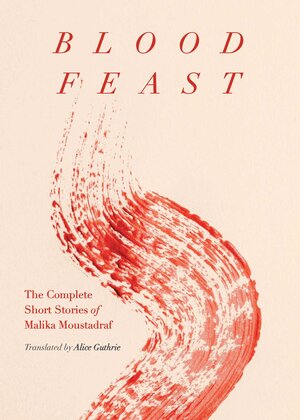

Blood Feast, a collection of short stories written by the late Malika Moustadraf, is a chilling contribution to a sadly slim body of works that highlight the plight of women in Morocco today. Moustadraf was an icon of feminism who did much to expose issues of gender and sexuality, and the collection pays tribute to her fearless exposure of gender-based inequality and discrimination.

The stories give a glimpse into the realities of Moroccan life today, in which women are financially dependent but in which conservative, patriarchal agendas reign. Despite some reported progress by women in Morocco in economic, political, and social arenas, Moustadraf’s stories highlight the enormity of the social and cultural barriers that still pervade. Reading her collection, the reader is under no illusion as to just how much work still remains to be done.

The collection, which is translated and curated by Alice Guthrie, features poor and working-class Moroccans: A wife is blamed for walking in bad luck when her husband is diagnosed with kidney failure; an officer gropes a woman and then tells her to cover herself up, calling her a “whore” as he passes by; a mother plots to ensure her daughter can prove her virginity – the injustice against women is breathtaking.

The story “Blood Feast” (which is also the title of the book), like many others in the collection, depicts a toxic environment in which women’s very existence is blamed for all that is wrong. Here, a mother-in-law blames her daughter-in-law for her son’s illness. The husband claims that the kidney pain began within the first month of his married life – and just in case we missed the point – the man in the opposite hospital bed sums up the overall attitude, suggesting dismissively: “…let’s talk about something more important than women – they don’t deserve all this attention from us, they’re just a crooked rib that breaks if you try to straighten it.”

This lack of sympathy for women – and indeed of empathy between women, between husbands and wives, and in fact towards the female sex in general – is evidenced in every story in the collection, bringing home to the reader the brutal realities of female experience. Nonetheless, these stories abound with contradiction and hypocrisy. In “Delusion” for example, a father threatens to disown his daughter for marrying a Frenchman, but is quietened by the promise of the money the marriage will bring. He eagerly anticipates the bottle of wine and the weed at the wedding, exposing on one hand a deep entrenchment of attitudes, yet on the other, the ease with which these attitudes can dissolve when material gain is added to the mix. And it is this Moustadraf’s talent: She quite expertly exposes a deeply rooted disdain for women, whilst simultaneously revealing the reliance that society has upon them.

Again and again, story after story, damning fingers are pointed at wives, sisters and daughters, evoking a powerlessness that suffocates. The reader, in witnessing this damnation is left aghast at first, then exhausted before finally feeling bereft of hope that anything might change. This capitulation is captured in the very aptly named “Claustrophobia,” – a story in which a young woman who is groped on a bus simply cannot tolerate any more. Silenced by her fellow travellers for calling out the man’s behaviour, she is forced to descend, unable to breathe any more of the bus’s dank air and oppression. But on this occasion as in so many of the stories, she emerges into the dark night to find that there is still no escape.

Moustadraf’s writing is stark, but therein lies its brilliance. She never shies away from an opportunity to evoke visceral images, make sensory assaults or weave complex and compelling characters that arouse empathy, disdain or outcry, as in the story, “Thirty-Six,” in which a father sends his daughter to the grocery store knowing full well that the owner is a far from pleasant character:

I don’t usually buy groceries from him. His eyes are crusted and red. He takes a snort of snuff, triggering an endless sneezing fit, then wipes his nose on a Grayson handkerchief that looks more like a strip torn off a floor sack, sticky with caked, doughy old snot. He opens the handkerchief, contemplating the contents, and then stuffs it back in his pocket.

Moustadraf hooks the reader in from the start, unfolding with the gentlest touch a vivid reality that has long-lasting impact. The reader is intimately placed in the Moustadraf’s world, and in this position is engaged, involved, and ultimately disturbed. Bringing to the reader hypocrisies, double-standards and brutal realities, each story, though only a few pages long, is anything but fleeting. Instead, they haunt the reader who is left bewildered for some time after, gazing at the page in disbelief.

Having grown up in a multigenerational household, I’m certain that what makes this collection a masterpiece is its ability to place the reader on the inside of Moustadraf’s world. It illuminates the importance of factors that dilute and challenge the reality of male dominance. It exposes the danger that comes where there is no pushback on the societal level, and when young women grow up absorbing hate for their own gender, rather than imagining a world of possibilities. It shines a light on all that is unacceptable and warns of what happens when we let slip the very things that preserve our humanity. And it speaks to the ludicrous attitude of those who hate without reason, when all that is rational and logical is twisted and contorted to fit the mold of preexisting beliefs. Humanity is the fundamental ability to respond to the human in front of us. When we cannot see that human in front of us any more, chaos and destruction ensue. With this book, Malika Moustadraf brilliantly demonstrates the power of literature to bring important societal issues not just to our attention but into our own living rooms. It shows too what is lost when a such a brilliant and enigmatic voice is no more.

Blood Feast

By Malinka Moustadraf

Translated from the Arabic by Alice Guthrie

The Feminist Press, 164 pages

Elizabeth Meehan

Elizabeth is a writer writing for the 21st century reader. Her work explores how the narratives, old scripts and stories we tell ourselves about who we are, and what we deserve, are often as fabricated as any fictional novel. Exploring the relationships we have with self and others in contemporary life, Elizabeth’s work pulls the reader not just into the story unfolding on the surface, but the characters inner world and family dynamics unraveling underneath. Elizabeth is unafraid to explore form to find the best way to tell the story being told that honours the story. She evokes an immersive reading experience, provoking the reader to engage with their own stories. Elizabeth is from Ireland and she has an MPhil in Creative Writing from Trinity College Dublin and a PhD in Sociology from Queen’s University Belfast.