You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

The board denies my application for parole, unmoved by my argument that my family had suffered enough, so I didn’t ask them to write letters of support, and so I stood before them on my own merit and my own word that I wanted to make something better of my life.

I can try again in four months. Fuck those assholes, I think as I walk to the edge of the bluff of this fenceless camp to stare into space before going to see Ms. Smith, the prison camp’s therapist. Other inmates walk by on the road that rises from the camp and circles the summit, past a radar dome left over from the Air Force, and the maintenance buildings and shops, before dropping down to the camp. I call it the teardrop because that’s the shape it makes. I hear guitars carrying over the desert. Brew and Flat-Five are playing the blues. They’ve been teaching me to play and sing. It helps me. I wish I had time to sit with them, but I need to go down.

October is ending. Ms. Smith has a jack-o’-lantern on her desk. She has painted her eyelids and her fingernails black and has on deep blue lipstick. Her blouse is black with red poppies like bullet wounds blooming. She smiles when I sit down and one of her teeth is missing – covered with black wax. I smile back.

“I love Halloween,” she says.

“It doesn’t show,” I say.

She laughs.

“It’s Lynne’s birthday too,” I say.

“I’d love a Halloween birthday. What did you do to celebrate?”

Two Halloweens ago I’d dressed as a soldier. Clever for a kid in the Guard. What did Lynne go as? A hippie possessed by the spirit of the dead? We went to our favourite bar where our favourite bartender, who never carded us, wore a tux and told everyone he had an offer they couldn’t refuse. Lynne dressed as a flapper. That was it. Her calling everyone darling, saying jeepers-creepers, singing “life is a cabaret,” and doing some vaguely ’20s dance moves. She smoked her cigarettes through one of those long cigarette holders and drank gin and tonics. She told everyone to call her Zelda, “Mad Zelda, darling.”

Why did I wear my uniform?

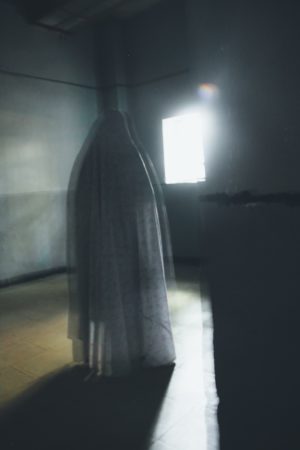

Did I feel like an imposter so I put on the uniform or was I just lazy? Do you dress like a normal nine to-fiver if your everyday getup is punk? Is it really a costume if you dress like a regular job? Maybe if you painted your face white with some blood trickling down the corner of your mouth or some fake fangs. Zombie hippie. Ghost biker. Vampire hooker with angel wings. Ambulance-chasing lawyer run over by next of kin. Dismembered construction worker. Franken-cop with an attitude. Poltergeist soldier coming to the end of his own days, because soon the house would be empty with no one to hear the crashing of pictures and glass against the floor. Do angry ghosts still rage with no one home?

In ancient times we dressed in costumes to trick the spirits into believing we were one of them. We shifted our identity and camouflaged ourselves out of terror. In our modern times we dress up almost as an excuse to act like someone we aren’t – to escape everyday life. For one night we walk among the spirits who wander the earth in search of the living to kidnap.

At the party, I started feeling down with all the drinks flowing and Lynne’s laughter like music. It crept over me like how the darkness comes in the open desert – the long twilight and then the black. It wasn’t like I was upset or angry or anything had happened out of the ordinary. In fact, it was a ripping good time with dancing and drinking games and everyone masked or painted and loose in the joy of life disguised from death.

As a boy, I would wear parts of my father’s Vietnam War uniforms and later in high school I bought surplus battle blouses and pants to wear. After I came back from basic training for the National Guard, I’d wear my camo pants off duty as part of my “image.” Here, I’d found an old flight suit and paratrooper boots in the supply cache and I wear them all the time now. I laugh. I end up two years later dressed like a poorly outfitted soldier on the edge of the frontier where the supply caravans only make it once a year if they don’t get ambushed and looted. What does this cycle of cast-off uniforms mean?

Ms. Smith writes in her notebook. “It’s part of manifesting what you want to be. In a way you are living proleptically. You feel, unconsciously, if you masquerade long enough, you will become the thing you desire.”

I wonder.

“You have to find a new way to dress to break free of the cycle.”

As we end the session, she tells me I must try harder with the parole board next time. No amount of desire will overcome the will of the state without the proper paperwork.

I leave and walk back up the bluff to watch the sunset. The radar dome blushes with the last light and Molly, who believes it’s an alien communication installation, stands under it staring at it like a pilgrim who has arrived at a holy site. He mumbles, his mouth twitches as he rocks back and forth before walking around it, always ending up at the same point he started from. Other inmates jog or walk past and some pause to watch the sunset. I can hear Flat-Five and Brew playing just around the bend. I figure I’ll turn around and not talk with them. I don’t much feel like singing any blues. The desert cools as I stand there. A guy they call Frog sprints by several times as the night spreads over the sky like blood on a gauze pad.

On this Halloween, I think of Lynne as I watch the stars materialise as if out of nothing. Her birthday. Twenty. Beautiful. Blonde. Stoned. I haunt this bluff, this falling darkness, living but not living. Pallid skin of the undead. Not dead. Not living either. No chains to clink in the night. But a ghost for sure.

J. D. Mathes

J. D. Mathes is a 2019-2020 PEN America Writing for Justice Fellow, a screenwriter with Rehabilitation Through the Arts, a recipient of the Norman Levan Grant, a Jack Kent Cooke Scholar alumnus, an award-winning author of four books, photographer, book critic, screenwriter, and librettist. He is currently working on a book length project with The New Press called ILL SERVED which will tell the stories of justice involved veterans and their experiences with mass incarceration. His script, In the Desert of Dark and Light, is in post-production. He loves his two daughters very much.