You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

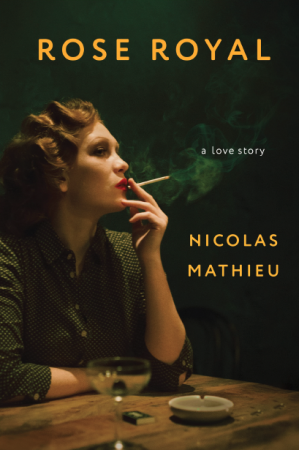

Rose is in her fifties – but still attractive, the narrator hastens to add, as if it is a surprising feature that forgives her age. Please keep reading. I promise, she has great legs.

A bit of an alcoholic, single, and mostly ignored by her grown children, Rose’s favorite place is the Royal, her local, where she idles her evenings away with a sociable bartender and her hairdresser friend. Rose seems mostly content with things as they are, but “sometimes it seemed like she was living her life on autopilot.” She’s done the dating scene, and it wasn’t very fruitful. She’s survived more than one abusive relationship, so she’s picky. After a surprising argument with her last boyfriend (“It was always the same old story. You touched the nerve of his pride and his fist came down on you”), Rose buys a revolver and carries it in her purse.

This seems to tell us all we need to know about our heroine: she faced a problem, dealt with it, and lives with the precaution against a recurrence every day. “At least she could be glad about one thing. The trials she’d been through had rewarded her with the unquestionable gift of her own resilience. Rose was a strong woman now. You only had to see the way she handled herself with men.”

Nicolas Mathieu published his first novel, Aux animaux la guerre, in 2014, and it was later adapted for television. In 2021, it was translated to English as Of Fangs and Talons. His second novel, a coming-of-age story, won France’s most prestigious literary award, the Prix Goncourt. And Their Children After Them is set in eastern France in the 1990s, but in Rose Royal Mathieu conjures a modern-day Paris with modern problems: Rose is employed, good-looking, comfortable in her own skin, strong-willed and intelligent. But she’s single, and she’s in her fifties. Can a woman of Rose’s age exist without judgement? In this way, Mathieu enters a category of fiction that is narrow and typically dominated by female writers. It would bring to mind Anne Tyler and Elizabeth Strout, if not for the severe conflict and minimal focus on character. In Rose Royal, almost everything we learn about Rose is connected to a single romantic relationship.

When an unexpectedly rowdy night at the bar turns even more unexpected, Rose meets Luc, and it’s all very different from the boring first dates spawned from this or that dating app. “The people we like always seem familiar, somehow.” The pair are quickly smitten with one another, and although Rose wasn’t expecting it, “Little by little she was lured into the swindle known as dependency.” But Luc isn’t perfect – he doesn’t say much, and the sex isn’t good. When she attempts to host an alcohol-free dinner in the hopes of a more successful sexual encounter, the evening proves to be a turning point in the relationship. Rose stops pretending everything is perfect, and Luc stops pretending to be perfect.

From here the novel lurches forward. Although Rose was relatively content with her life and work before Luc, she slips into the ease of being in a relationship. However, Mathieu seems to imply that Rose is won over by Luc, despite his faults, by his wealth and success. He has a comfortable country home and takes her to fancy bars where he buys her drinks. He drives an Audi Q6, Rose notes, and pays for dinner in cash. “In a way, Luc’s success was also hers. It enveloped her like a sweet scent and soon she couldn’t tell the difference between that pride and her desire…Her new life was like being on vacation.” For an otherwise complex, wise character, this seems a too-simple device to distract Rose from the many red flags she sees in Luc. Surely it is more complicated than material comfort: the desire for companionship, loneliness, believing that it will soon be too late to find love, or that there will be no one left. But her fall into submission leads to a willingness to overlook the worst – an all-too-familiar mistake that, for Rose, risks dramatic consequences.

Almost from the outset, it seems that the “love story” presented here is superficial at best, but Rose and Luc hold on – for what? She is acutely aware that Luc is not a match. She considers leaving him many times, confides in a friend, admits he is abusive. But the preoccupation with Rose’s appearance and age, her string of failed relationships and her “autopilot” existence perhaps prompt her to dismiss flaws that she might otherwise have been loathe to ignore. “She had reached that difficult age where what remains to you of youthful vigor and electricity seems to be vanishing under the rising tide of days…Words like ‘firming,’ ‘cellulite,’ ‘hematite,’ and ‘collagen’ had become part of her vocabulary.”

Maybe she thinks this could be her last chance at love. Maybe she thinks that Luc is the best she can hope for. Or maybe she has finally tired of defying the expectations of a woman her age.

By Nicolas Mathieu

Translated by Sam Taylor

The Other Press, 96 pages

Monica Cardenas

Monica Cardenas is a writer living in the U.K. She holds a PhD in Creative Writing from Royal Holloway, University of London. Originally from Washington, D.C., she earned a BA in English from Wilkes University, Pennsylvania. Her novel-in-progress The Mother Law was longlisted for the Lucy Cavendish College Fiction Prize and runner-up in the Borough Press open submission competition. Her writing appears in Litro, Sad Girls Club Lit, and Catatonic Daughters.

- Web |

- More Posts(3)