You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

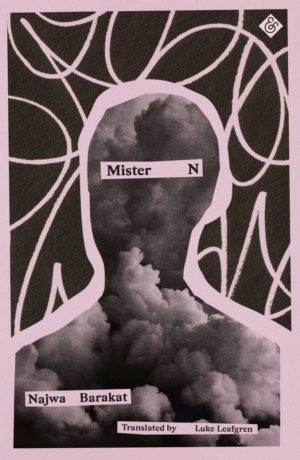

Mister N, the latest novel by Najwa Barakat, originally published in Arabic in 2019, is a haunted book. The novel is populated with the dead and deals with the inevitability of death and its insatiable hunger. The turns and twists of the plot will haunt its readers who, upon reaching the end of the novel, will return to re-read it all again. It is a complex, beautiful, poetic and disturbing mediation on human existence, on family, love, war and loss, and on the power of creative writing.

It is difficult to discuss Mister N without giving too much away, since nothing in the novel is straightforward. All the facts and details can be read and understood in different ways at any given moment, and the reader is constantly kept on their toes, as if they are reading a whodunit, unsure of the crime or the victim. The novel requires a willingness to accept the narrative, while at the same time asking its reader to offer alternative interpretations to the reality it presents.

The protagonist, Mister N, is an aging writer, trying to find his literary voice and to resume writing after a long period of silence. In order to reawaken his literary creativity, Mister N turns to the Biblical story of Lazarus of Bethany, who was raised from the dead by Jesus. According to Mister N’s retelling of this miracle, Lazarus does not want to return to life. He is blinded by the light and then turns to Jesus, asking accusingly, “Why, O Lord? Have I done something to displease you?”

Alongside the fictional retelling of the Biblical narrative, Mister N also tries to tell his life story, and we are never sure whether what we read is life experienced, or the writer’s notes as Mister N is an unreliable narrator, who deliberately deceives. His name is never revealed in full, and he teases the reader by mentioning the fact that the mug he is drinking from “had his name written on it in black ink.” Mister N, however, writes in pencil, adding and erasing, changing and retelling, with each section of the novel set as a new attempt to tell his story afresh. We are drawn into the drafts and the possible versions, collecting the ghosts and pieces of the puzzle that make up the enigma that is Mister N. There is a deliberate choice to frustrate and exhaust the reader, for the narrator is no longer interested in a readership. He does not want to reawaken the memories that make up his narrative, and yet he feels compelled to do so.

Mister N has metaphorically buried himself, comfortably remaining within a hotel room. He does not want to venture out or have any contact with the outside world. Already as a child he created a little cave for himself, a separate section on the balcony of his family home, but when his corner of tranquillity is under threat, he replaces it with the hotel room. A tower block is being constructed across the road from his building, growing taller, overshadowing his home, much like his older brother Sa’id, who is taller and more successful and their mother’s favourite son. While unable to escape his brother’s shadow, the hotel room does seem to offer Mister N a safe haven, at least initially. However, this comfortable, yet characterless, space does not exist in a vacuum. Already on the first page we find Mister N by the window, helping a fly to find its way out. Windows and insects reappear thoughout the novel, as the city of Beirut stands bare on the other side of the glass pane. Mister N remembers being a child and seeing long queues of poor and desperate patients outside their window waiting to be seen by his father, the doctor. Mister N was also the only witness to the moment when his father walked out on him, climbing out of a window and literally walking out into the void, to his death. The calmness and quiet of the hotel room is a deceit.

The echoes and the memories of the war are everywhere. Everyone it seems has been damaged, scarred and maimed, even the smallest of creatures:

“Our mosquitoes and other local insects have developed quite the work ethic in recent years. They toil now not only to feed themselves, but from the pleasure of causing pain, which, having tasted once, they find impossible to relinquish. Rats, mosquitoes, flies, cockroaches, feral cats, pariah dogs: all of them are vicious now and liable to get drunk on the simple taste of killing, much as humans do. Their transformation began during the civil war, when they first grew strong on the bodies of the slain, which were of course lying in the streets wherever they fell. Even when the calm years came, these creatures, having acquired this addiction to our flesh, wouldn’t relent, and soon reached unprecedented levels of savagery.”

Violence pervades the novel, and when his privileged life seems to cover it over, Mister N goes out of his way to find it. The Beirut he finds outside his window is a multi-racial, multilingual, poor and violent slum. It is foreign, alluring and violently real. Outside his room, in the streets that hit him with a strong cacophony of colors, smells and sounds, he meet Luqman, a character from one of his novels, who is alive and real. This encounter re-introduces the theme of resurrection, of the walking-dead, and the question of the responsibility of those who give life to others. It explores the notion of guilt as inherent to the role of parents, creators and miracle-makers.

In the heart-of-darkness that is Bourj Hammoud, Mister N also finds an angel, the foreign sex-worker Shaygha, who takes him under her wing and brings him back to life. She revives Mister N and gives his life meaning, but like the Biblical Saviour, her selfless devotion results in her ‘crucifixion,’ in the senseless killing of an innocent victim.

In the most dramatic moments of the narrative, Barakat reminds us that we are reading fiction and that the characters and events are imagined representations whose joys and tribulations are part of the human condition. War, torture and injustice are all too common, as Mister N admits:

“Then I realized that I was bargaining for a human being, and haggling with the buyer over the price! God! And they say that the time of slavery has passed, never to return. No! We’ve never had the freedom people claim we possess. For as long as we are the slaves of ourselves, the slaves of our families, the slaves of our feelings, the slaves of our impulses, the slaves of our society, the slaves of base and unjust life, the slaves of masters and the masters of slaves, we will subjugate and be subjugated because of skin color, because of geography, because of money, because of gender, because of status, because of weight, because of climate, because of shit, because of… we will enslave whosoever may be, howsoever we may, always and for all eternity.”

One possible way out of this misery is death. Fiction is another and itis closely linked to the third option – madness. Indeed, the novel offers a painfully convincing image of a tormented mind, with its deliberate blind spots and constant need to reinterpret reality.

Shifting from descriptions of intimate and close up moments, to musings on big themes, Najwa Barakat masterfully weaves together all the threads of this incredible fiction into a powerful and moving story. While her first-person narrator is not always a terribly sympathetic character, the novel is nonetheless full of compassion, depicting one man’s desperate search for humanity. More importantly, perhaps, in a time when so much else is clamouring for our attention, it is also a heartfelt defence of poetry and fiction, a reminder of the necessity and importance of creativity:

“Don’t they know that what we dream becomes reality, fully real, from God all the way down to Satan, and that whatever we give a name to immediately rises up before us, and takes on flesh and blood? Don’t they know that the stories we tell are the ghosts that secretly reside within us, the demons hiding in the closets of our souls, the brothers of all our misfortunes and disappointments in this life?”

In the translator’s note, Luke Leafgren comments on the challenge of translating this novel without resolving the ambiguities or removing the obscureness of the original. His work is a triumphant success and both he and his publisher should be commended on making Mister N available in English, as it is sure to become a modern classic.

By Najwa Barakat,

Translated from the Arabic by Luke Leafgren

And Other Stories, pp. 272.

Tamar Drukker

Tamar is a lover of words and languages. She completed her PhD at the University of Cambridge and have written on the readers of Middle English manuscripts and on chronicles. She has taught Hebrew and Israeli Studies at SOAS, University of London for over 15 years. She is a freelance literary translator and would happily spend all her days reading.