You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

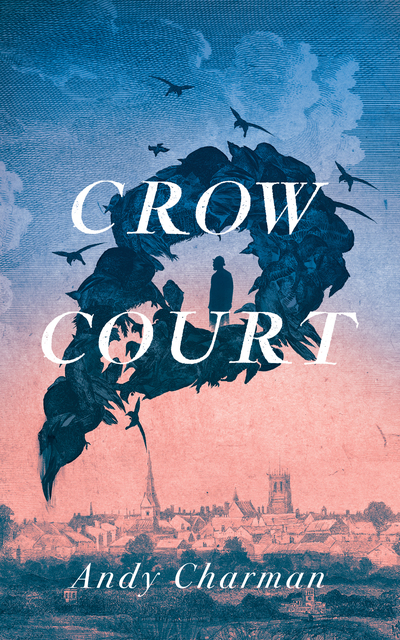

Andy Charman’s debut novel, Crow Court, is a carefully curated, episodic tale of how tragic crime is. It is not just a question of who to blame, but rather who is touched by its wide-spreading wings.

The story opens with a bird’s eye view of bustling Wimborne, fluttering in and out of various buildings to introduce a few of the characters with an almost theatrical ellipsis before each name. The suicide of a young choirboy, Henry Cuff, and the subsequent murder of the disreputable choirmaster, Matthew Ellis, soon launch us into the grieving, gossiping inhabitants of the Dorset market town, whose lives are shown to be intricately interwoven.

The plot centres on a group of childhood friends who are unfortunately embroiled in the aforementioned deaths: Charles Ellis, John Street, and Bill Brown (and his brother Cornelius). Country bumpkins by birth, they face conflicts of class, justice, corruption, and love.

Although Charles might be called the protagonist, and is often the narrator, we follow the story through the eyes of various characters, even those very distant from the main plot. I quite liked this Greek-chorus-like use of the community as detective. It isn’t presented as a collective witch hunt, but rather gossip, relationships and passing conversations which slowly reveal to the reader what is going on. Alternating between close third person and first person, even briefly venturing into second person narration, Charman presents us with a plural, communal narrator, which is a pleasure to read.

As the title would suggest, crows feature heavily in the book, along with peacocks, blackbirds, starlings, and woodpeckers. The presence of birds within the novel is always soaked with significance. They, along with the Wimborne community, act as detectives and judges, leading, and misleading, the characters to the final culprit. Their role within the book does not quite push it into the realm of magical realism, but it sits in a liminal space in terms of genre. Omens and superstitions certainly have their part to play.

I really enjoyed the themes explored within the book, most notably that of class. Various subplots explore issues caused by class, such as that of Cornelius Brown who returns from India wealthier and more well-spoken than his brother Bill. Charles feels both a class traitor and a bumpkin, as his thriving wine business has him rub shoulders with the upper class. His money pulls him and his sister Selina out of poverty, only for her to “sneer at those souls they’d left behind.” Within these stories and others, class severs families, friends and lovers; right and wrong.

The fact that class plays a role in the law and morality is significant in a crime novel. One of the customs men within the book, humorously named Mr Domoney, talks of the ‘criminal classes,’’ making it clear that the government and law cannot separate poverty and crime. The magistrates and justice itself are driven by money, and this too is explored within the book right up to the devastating ending.

The period in which the novel is set is fruitful ground for these conversations. The world is at the cusp of change, with trains chugging their wealthy passengers towards the future, gas lamps lighting their way. Cornelius is caught up with the changing world and now belittles his older brother for lagging behind, laughing at Bill’s terror in the face of a train, or as he calls it, “the devil!” But as Bill Brown asks as he argues with his brother, who does progress leave behind? The rural, fecund Wimborne and its workers oppose the mechanical progress spoken of by the upper classes, because it pushes them further into poverty. As Bill makes clear, however, the natural world is cyclical; automated, linear progress doesn’t fit. In fact, the final chapter undermines this notion of progress, when Reverend Giles Cookesely is observing two-hundred-million-year-old fossils. We are reminded that our “progress” is arrogantly short-sighted. At a time when AI and tinier technologies are displacing the world as we know it, this novel feels critically relevant. As with all successful historical fiction, Charman converses with the past about the present and future.

Alongside these serious, grand subject matters, tender moments outside of the main plot lend the narrative a delightful poignancy. Such as the tale of widowed Sidney Wilkinson, who is sleepwalking through his grief at the death of his wife and unborn child. He plays a part in uncovering the murder, but this does not seem to be the main point of his tale. The story of Walter Pugh works in a similar way, another victim of the cutthroat class barriers, with his sad, ageing father.

As well as exploring interesting territory with his content, Charman pushes the boat out with his language. There is an interesting syntactical style in the opening chapter in which many sentences lack pronouns and main verbs. This creates a syntactical instability, keeping the narrative on edge and somewhat outside a concrete sense of time. Although slightly distracting at first, this unsettling style feels fitting for the chapter in which the main death occurs and causes chaos in the community.

The use of Dorset dialect for some of the characters is effective. A helpful glossary at the back of the book explains all the terms, although it is mostly unneeded since most of the meanings are clear in their context. This prevented any slowing down in reading the book as I didn’t need to be constantly flipping back to decipher a meaning.

The book as a whole is written beautifully. Charman’s afternoons age and his nights die, his skies are decorated with clouds and blotted with crows, his crows fold their wings like tall aristocrats stowing umbrellas, his candles bleat their weak glow while his gas lamps wink from the silver cutlery, and his hats are stolen by thieving gusts of wind. This adds to the novel’s overall charm and sense of mastery.

Although I enjoyed the episodic way of telling the story, a couple of the stories left me interrogating their relevance to the main plot. Although lovely tales in and of themselves, they read more as short stories rather than chapters in a novel and I was eager to find out more about the murder and its suspects.

As for the suspects, I did find the eventual revelation of the murderer somewhat predictable, although not unsatisfying. The character I had in mind as the culprit turned out to be just that. However, the crime was not morally clear, and the narrative seems more focused on telling its characters’ stories, rather than rushing to solve the murder mystery. For this reason, the relative predictability of the ending does not detract too much from the enjoyability of the read. What’s more, the tying up of the other characters’ stories was both surprising and emotional: a brilliantly conceived way to finish. This delectable debut novel is no straightforward murder mystery: the innocent die, the murdered are evil, the suspects are good, and justice is corrupt. All distinctions between right and wrong are blurred by the love of money and the desire to have a place in the new, fast world. Murder itself is only wrong when pinned on the lower classes; the distance between legality and morality has never been further. As John Street says, “the magistrates don’t care f’ right nor wrong. … They care for themselves and their bank books. … Wrong or none don’t make much difference.” Intriguing, clever, and charming: I was sad to finish it as quickly as I did.

By Andy Charman

Unbound, 336 pages

Zadie Loft

Zadie read Classics at Downing College, Cambridge, and is currently studying for an MSt in Creative Writing at Kellogg College, Oxford. She has previously been a columnist for the Cambridge Varsity newspaper and a prose and verse contributor for La Piccioletta Barca. She is Litro's Editorial Strategist.