You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

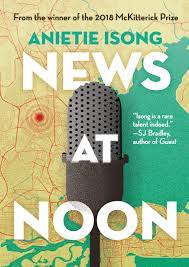

Anietie Isong’s second novel revisits the territory of his McKitterick prize-winning debut, Radio Sunrise: a Nigerian public radio station where the employees fight (with varying levels of enthusiasm) the decline of “ethical journalism.” This time, returning protagonist Ifiok and his colleagues must push back against the headline-grabbing disinformation and hysteria that both feeds off and exacerbates the country’s Ebola pandemic.

Reviewing a sequel when you haven’t read the original makes an already self-conscious reviewer even more distrustful of the whole enterprise of reviews. The gap between my experience of encountering this author and his characters for the first time, and the experience of a reader who has already spent 228 pages (the length of Radio Sunrise) in their world, is going to be quite wide. So it feels important to say up front that my working assumption for this review was: if you’ve read and enjoyed the first novel, you’re already likely to seek out the second. That being the case, this review is probably only of use to people who, like myself, are discovering Anietie Isong’s fiction for the first time. And as a final pre-emptive justification for trying to write about this book, (which I will do in the next paragraph, I promise) I would also point out that the blurb and front cover are both silent about the fact that this is a sequel. This suggests it’s totally fine to consider News At Noon as a standalone story, and that’s the premise that this review (finally) starts from.

Inevitably, releasing a novel about any kind of pandemic into a world that’s still in the grip of COVID-19 means it can’t possibly escape comparisons. News At Noon is set during Nigeria’s very-real 2014 Ebola outbreak, the first of its kind in a West African country. As with COVID-19, the response follows a familiar trajectory of panic, misinformation, ineptitude and mass surveillance. There’s a sort of grim satisfaction that accompanies this game of spot-the-similarity, especially when it comes to aspects of the pandemic that you might have forgotten about. There’s a moment in the book where Ifiok and co. receive a shipment of thermal scanners: “Chief Azubuike’s personal assistant showed us how the hand held devices worked. From a short distance – around six inches – he pointed the device at Julius’s forehead, and the infrared technology estimated his body’s internal temperature.” This set off a strange nostalgia for me – the memory of a National Express driver waving what looked like a barcode zapper at my forehead before letting me on the bus. Bringing the thermal scanner to mind, I felt oddly fond of it – the same faddish affection I feel for a PlayStation light-gun or Premier League football stickers.

Knowing the outcome of the Ebola pandemic does blunt some of the book’s impact. The outbreak was contained in a matter of months, the death rate confined to single figures. Of course, for anyone to whom those single figures were real, singular figures, the relatively positive result would have offered little comfort. For the purposes of the novel, though, it’s hard for the stakes to feel high when 1) the scale of the pandemic feels small when compared to COVID or the wider African context of the Ebola pandemic: nearly 5,000 deaths in Liberia, almost 4,000 in Sierra Leone, and over 2,500 in Guinea and 2) the virus feels largely absent from a lot of the book.

Conversely, that absence points to one of the novel’s strengths: it deftly captures the astable experience of living through a pandemic – that flip-flopping between a state of macro-level panic and the fortunes of everyday mundanity. Ebola is just one concern among many for the protagonist. Often it loses ground to the excitement of Ifiok’s love life or the contest over who will become president of the Society of Journalists. There’s also a lot of pages given over to descriptions of food, whether the preparation of a meal or the rating of a restaurant’s fare: “The food arrived. I took a spoonful of the fried rice and the mismatched array of spices exploded in my mouth. I hastily sent the meal down my throat…If this was her yardstick for measuring palatability, then I was inclined to believe she had poor taste. I would choose The Lord Is My Shepherd Foods 100 times over. Their spices blended seamlessly with any type of rice.”

This focus on the quotidian might be construed as a sort of mindful response to the memento mori of the pandemic – a commitment to focussing on the pleasures of the here and now – but there’s also a danger that the reader starts to slowly disengage when repeatedly met with such unremarkable descriptions. Similarly, some of the day-to-day threads were easier to invest in than others. Ifiok’s romantic entanglements felt a little caricatured – the comedy of his mother trying to set him up for marriage whilst he embarks on a love affair with his boss is handled in such a way that none of the female characters feel nuanced enough to become more than ciphers. On the other hand, the election campaign for President of the Society of Journalists is much more dramatic, bringing to life one of the book’s major themes: the battle for the very soul of journalism. The biggest threat to the News at Noon’s candidate (representing sober, responsible, facts-foremost reportage) is Samson, a superstar blogger and purveyor of shamelessly sensationalist click-bait. Samson has a vibrancy that propels him beyond being a simple foil to Ifiok, his vision of 24-hour, as-it-happens, crowd-sourced news proving seductive even as we remember what havoc relentless and unchecked content can wreak: “There’s no point waiting until the afternoon before giving people the news. Give it to them as it breaks! That’s what my news site does…Even so-called established international media put out wrong information…The BBC sometimes makes mistakes. To err is human…I pay my freelancers. Many of these so-called media houses don’t pay their interns.”

I won’t say how the election turns out because I don’t want to ruin that part of the plot for anyone, but I will say that the result – or the way the result is reached – felt like a particularly sobering comment on the journalism wars, and the tactics that might have to be employed if traditional media wants to stick around on anything like an equal footing. What News At Noon ends up being, then, is a sort of capering comedy, set against the backdrop of a pandemic, which throws in some legitimate and thought-provoking concern around the influence of new media, and mixes this with a good deal of fairly banal observation. Unlike the spices used by The Lord Is My Shepherd Foods, these elements don’t blend seamlessly, but there is plenty to chew over. Some aspects keep repeating after the meal is finished.

By Anietie Isong

Jacaranda Books, 228 pages

Adam Ley-Lange

Adam Ley-Lange lives and writes in Edinburgh. He's currently trying to find an agent for his first novel, whilst working on his second. Adam is also an editor for Structo Magazine, which publishes short fiction, essays and poetry.