You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

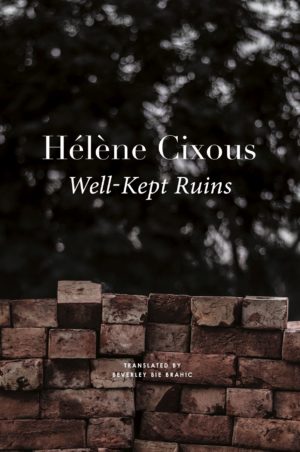

Well-Kept Ruins (originally Ruines bien rangées) is Hélène Cixous’ latest genre-defying work, impressively translated by Beverly Bie Brahic to transport Cixous’ swirling streams of consciousness into English. Both autobiographical and biographical in regard to her mother’s life, Cixous explores the liminal space between fiction and fact, memory and history, novel and memoir.

Centred in Osnabrück, she remembers many of the city’s horrors as she walks through the city: 16th-century drownings of witches and midwives, the 17th-century Thirty Years’ War, the 20th-century persecution of Jews of which her mother was a part. Pictures are provided to guide the reader and remind us that the text is located in a real place, despite its unannounced fluctuations through time, a place that Cixous had just visited in 2018 to receive the Justus Möser Medal. Alongside these larger histories, the reader is also presented with intimate, individual stories which add a sharp poignancy to the horrors she describes: we are told the story of Frau Skiper, a midwife who was drowned in 1561; Ilex, a pseudonymous writer who was killed for their anti-Nazi journalism in 1933; Elfriede Scholtz, writer Erich Maria Remarque’s sister who was killed by the Nazis; and Grete K, a classmate of her mothers who was turned away at a food bank because she was a Jew.

What I liked most about the book was its explorations of history and memory in relation to Osnabrück. These are big and complex ideas, yet Cixous manages to cover a wide range of nuances within them, letting the reader explore these themes as much as she does so herself. The book is, in her own words, a form of “archaeology,” both of Osnabrück and her mother. Cixous unearths the core of the city, its history and memories, as well as the core of herself, acting as the “Archaeologist of Eve,” her mother. Like Freud with Rome, Osnabrück is a place where Cixous can use the physical layers of history to explore the figurative layers of memory. One example she offers is in a street named after Elfriede Scholtz who was killed by the Nazis on a dubious count of “undermining morality,” largely believed to be a cover for the real reason: wanting to punish Remarque for his anti-war book, All Quiet on the Western Front. Cixous tells this sad history, and then asks whether Remarque should walk down Elfriede-Scholtz Street, treading on his sister’s body, or not? With this question, she reveals how the city maps out its history, but also confronts the futility of concrete commemorations of the past: Elfriede-Scholtz Street does not bring back Elfriede Scholtz.

It is this disconnect between the physical city and its amorphous memories which drives the title of the book. The well-kept ruins of the title are the remains of Osnabrück’s Synagogue, built in 1906 and destroyed in 1938. This destruction and trauma remain at the heart of the city, a constant reminder of the past and its pain. In the book, Cixous discusses the ruins with her son, who dislikes their concealment of the destruction. They are too neat, sterilised, and removed from what they are ruins of. For Cixous, their neatness, which is labelled and placed in a cage, is the perfect representation of her own inner ruins.

The description of the ruins also opens up discussions about representations of these histories and memories. The book’s engagement with various forms of representation works well. In one scene, the author verbally describes a photo of her mother and classmates, and laments the photo’s inability to capture thoughts. When discussing Osnabrück’s Synagogue, she mentions Felix Nussbaum’s painting of it, and how the destruction of the Synagogue was something impossible to represent. Many other textual representations of history are referenced, such as Shakespeare’s Richard II and Homer’s Iliad on the Trojan War. While looking at these artistic renderings of the past and history, she explores their shortcomings: how can art ever capture the pain and complexity of reality?

As we reach the end of the book, it becomes clear that its main character and focus is Cixous’ mother, Eve. Her mother’s presence – and significantly, her absence – drives the plot, and grounds the horrific explorations of trauma and history in a very personal and poignant grief. More than anything, the book is a biography of Eve, a collection of her ‘long lives and many adventures’: how she left Osnabrück, was imprisoned in Algeria, returned years later to Osnabrück as a guest, and died in 2013. In the final chapter, Cixous clears her mother’s apartment and feels the immense grief and loss as her last remaining physical form, the apartment, is emptied. Her mother’s story is one of relentless displacement and escape, symbolised in the book by her suitcase. Eve left Osnabrück in 1928, returning only in 1935 to save her own mother, and was then forced to leave Algeria in 1971. Since the book is written in French but largely set in Germany, the fragile boundaries of her national identity are called into question. As her mother says, “nationality is an illusion, a fiction based on people’s geographic stupidity.”

The experimental style of the book does make it a challenging read. Punctuation is often unused, sentences are divided over paragraphs, and one thought starts before another has ended. At times, I was struggling to grip onto the story and follow the meandering stream of consciousness that is so characteristic of Cixous’ prose. She addresses this in her book, describing her style of writing as if in a dream: “you could recount the silliest nonsense, extravagate, vanish into tunnels without fear of exaggerating, even disappear in the middle of a sentence and wake on morning inside an obscure building not knowing how you got there.” As you can imagine, this is not an easy style to follow.

The other difficult aspect of the read was the occasional German word or phrase used by Cixous and left untranslated by Brahic. While I understood the motivation behind leaving it untranslated – it adds to the tension between Eve’s German and French nationality and heightens the inaccessibility across those national borders – it did make understanding certain difficult passages that much harder for someone who doesn’t speak German. I thought footnotes might have avoided this difficulty, as they were used clearly elsewhere by Brahic when Cixous’ French wordplays had no equivalent in English.

However, understanding that this book is not a novel, nor a historical account which follows a linear, chronological trajectory, eases its difficulties. Conversations are woven into streams of thought which creates a thick, vivid texture of the moment or memory being described. Regarding her philosophical musings on time and history, some I grasped, and some I didn’t. It isn’t easy to follow logically at times, but it certainly is easy to feel.

I recommend this book to anyone who is prepared to open their mind and lean into its challenges. Reading this book is like walking through a post-apocalyptic city, with glimpses of histories and memories intermittently coming into focus as you wander through the streets. It is fractured and complex, just as grief, memory, and generational trauma are. My occasional difficulties with reading it are perhaps a testament to Cixous’ success in capturing these abstract ideas: it isn’t supposed to be easy. Despite the painful subject matter, it did contain elements of hope in its interaction with generations. Cixous tells the stories of her mother and grandmother as she visits the sites of these stories with her own daughter and son. There is an implication that telling these stories to her family will heal the family history and memory. The grief feels closer to relief than sadness. To release the healing power in these stories, they have to be told and read, no matter how difficult or painful it is to experience them.

By Hélène Cixous

Translated by Beverly Bie Brahic

Seagull Books, 156 pages

Zadie Loft

Zadie read Classics at Downing College, Cambridge, and is currently studying for an MSt in Creative Writing at Kellogg College, Oxford. She has previously been a columnist for the Cambridge Varsity newspaper and a prose and verse contributor for La Piccioletta Barca. She is Litro's Editorial Strategist.