You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

When I travel from home to university, I always take the usual path: down the same streets, see the usual flood of people, hear the usual cacophony of voices. At all twists and turns, however, I feel like I’m on the edge of a chapter. A new setting, new groups of people, running off from where the last one ended – until I reach my destination. Each time I walk or take the bus, it is like a rehearsal of a story. And, whenever I decide to take a short cut or different bus, suddenly the course of things changes. This is how I felt reading Rogelio Braga’s newest short story collection.

As hinted in Abalajon’s introduction, this collection of stories has elements of cartography, reading each story feels like taking a turn on a street and getting lost in a new neighborhood. However, the collection doesn’t simply offer a whirlwind tour that narrates again the fixed imagery of the Third World sensory ordeal. Rogelio’s short stories, as translated by Kristine Ong Muslim, act almost as a counter map, one that highlights the laughable and lamentable plight of ordinary people in their everyday life, with the issue of labor at the forefront. Echoing De Certeau’s Walking the City instead of positioning the reader sky-high, with a panoptical view that reduces the city into a static show, the stories take us to the pedestrian level. The brevity of a walk makes us know that this is only the beginning of meaning, yet the grounding sense it gives us affirms the things we see.

Most of the characters’ movement in this collection can be summed up as deadlock. The first word of the first story, “Bona Bien,” meaning stalemate, outlines the insular system of violence in which many of the characters find themselves. In this story Soledad, freshly graduated from a prestigious university, gets dragged into the all-consuming cog machine of the corporate world. A world that that values money more than the worker’s livelihood, and where romance grows cold “fast like the coffees in Starbucks.” Things change a bit when she strikes up an unlikely relationship with Bona, someone who is almost the complete opposite – of lower background and rank despite having been in the company longer. Yet, when Bona’s situation unravels into a dire situation, Soledad can’t do anything. Nevertheless, even when she rejects a promotion and quits the company, the ending doesn’t seem to guarantee that Soledad can truly walk out from the path set up by the system. Alone in the cinema, she finds only temporary consumerist relief from everything.

The circular path that hinders one’s capacity to disrupt this by-product of capitalism is felt again in “Ministop,” where the rules of the game intercept the possible profound connection between two characters and make sure that their paths never align. Likewise, the story “Flirt of Rural Tours” troubles the crossing between two different communities. Yet, even when we are aware of the system, we cannot escape as is shown in “At the Outpost,” where the characters end up giving into this “transactional form of intimacy.” Indeed paths towards change, even when presented, sometimes seem more sinister than the violence that one is currently enduring, as in the titular “Is There Rush Hour in a Third World Country?” Similarly, the story “Two Missing Children” demonstrates how under the wrong hand, changes are simply over-the-top antics that stray us away from the actual issue.

This everyday violence is mapped out within families too. Both in “All the Quiet Sundays” and “Beloved,” this is a result of labor conditions, or rather, labor conditions become a way for the characters to rationalize the violence into an order or a pattern that helps them to maneuver within it. Yet, as the narrator in “Beloved” warns his nephew, “don’t bottle up your anger for any of us,” suggesting that resentment for the background you happen to be born into might recycle the violence rather than set you free. In this way, yet another form of deadlock is presented and even in this counter map, the cul-du-sac is inescapable.

In taking the reader through all the nooks and crannies of the city, the stories also convert the invisible into something visible, giving those who sometimes come to the edge of our memory a story – an approximation of an identity. In “Emilio Echeverri,” the narrator spends the entire story figuring out whether or not Emilio truly existed, when all of her friends seem to deny his existence. Using a speculative mode, “Piety in Wartime” also explores the terror of forgetting and of erasure, as one single man becomes the only person who can connect the past into the future of a people whose history is suppressed: “My work is for the history of every person, of every important event in a person’s life. I use my hands to impart onto the cloth every event and people’s important experiences so that the next generation will know their ancestors. They will know their origins.” It is like when old buildings and roads are demolished and reality seems to have severed its material connection to the past, making it hard to remember anything other than a hollowed-out shell of a what was once there.

Despite all this remapping, the landscape isn’t necessarily reshaped. Sometimes, those marginalized are made visible on the map, but only to segregate them further as in “Fungi.” Sometimes, people seem to be stuck in between, in a kind of irrealis mood. The final story begins with Lipoy – one of the few older characters in the collection – who is in search of a job. Despite his impressive technical skill, his service is undervalued and he struggles to secure income. However, as the story unfolds, more characters are introduced and the scenarios become increasingly surreal. One of them slowly begins to turn literally white, becoming invisible to everyone but one other person. Embodying the central theme of memory, visibility and labor, “Plural” embodies the intersection between all that is, that could be and should be. Interpellating its semantic as well, the intersected lives of the characters in this story mirror all the ways roads and streets intersect. Nevertheless, because one rarely stops and looks at the intersection, at where the other possibilities are, they evade our sight as if non-existent, like the characters in the story, and sometimes we can only bear witness from afar.

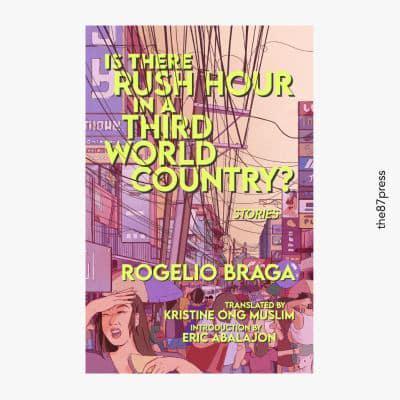

The rhetorical nature title Is There Rush Hour in A Third World Country? definitely grabs attention, along with the eclectic burst of pastel purples and pink and the neon yellow font. And if you have yet not caught on, “yes” is the answer to the question. Just as we often fixate on destination during our commute and overlook the paths we take, this self-evidentiality also challenges the reduced and fixed image we have of things. Rogelio Braga’s stories play with face-value images and pre-conceived ideas, reminding us that we often need someone to make a rhetorical remark in order to evince change. Many of the characters are aware of the system of violence, yet are unable to navigate out of it, either through sheer powerlessness or forced choice. Perhaps it is simply that the map they draw only leads to another dead-end. Therefore, in a way, their movement feels almost like being stuck in a congested street during rush hour: everyone wants to be somewhere but are incapacitated by the space, and silently poisoned by all the pollution. Regardless, like Muslim’s translation which is marked with Filipino signs, inviting non-Filipino readers to look at those rarely taken roads, the collection presents an opportunity for each reader to think about how they can walk in order to map a new itinerary of empathy. Cartography is a way for us to organize knowledge, and a walk is what grounds those ideas in reality.

Is There Rush Hour in a Third World Country?

By Rogelio Braga

Translated by Kristine One Muslim

The87press, 200 pages

Phương Anh

Phương Anh Nguyễn is a translator, writer and an editor at GENCONTROLZ. Their words have found a home in magazines and blogs such as Asymptote, PR&TA, Interpret Magazine, Agapanthus and forthcoming on SAND. Currently, they are doing cultural studies at University College London, and are a part-time bookseller at Waterstones.