You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

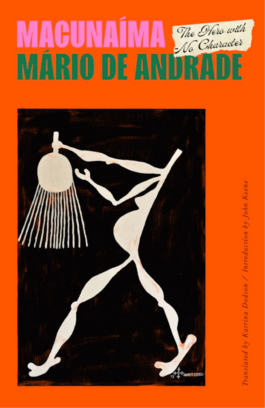

Originally published in Portuguese in 1928, this new translation of Macunaíma by Mário de Andrade is expertly realised by Katrina Dodson. Often hailed as a classic of Brazilian modernism and a precursor to Latin American magic realism, Macunaíma is a complex, often perplexing picaresque that takes the reader on an incredible journey through Brazilian folklore, mythology, language and culture.

Taking place over hundreds of years, this expansive, exuberant rhapsody follows the story of the shapeshifting, magical Macunaíma, “the hero with no character” and his two brothers, Jiguê and Maanape. Born in the Amazon heartland, Macunaíma is a mischievous, precocious – and sexually precocious – child who can only be coaxed to speak one phrase: “Ah! just so lazy!…” (This becomes Macunaíma’s signature phrase and is often heard throughout the book.) When he turns six, he is given some water to drink from a rattle and he starts talking like everyone else, asking his mother to take him for a walk. Eventually his (much older) sister-in-law, Sofará, is convinced to take him and during this walk Macunaíma transforms himself into a grown man and has sex with her. This happens a number of times until his brother Jiguê follows them and finds out what is happening. Furious, Jiguê takes a new wife, who Macunaíma also sleeps with having been transformed permanently into a man when a dish of poison yuca water is thrown over him. And so begins the running gag that whoever Jiguê falls in love with will also end up hooking up with Macunaíma.

This also rather sets the scene for the way things develop. Macunaíma is a mischievous, cunning but witty confidence trickster, who is always up to no good and gets involved in ever more elaborate capers and grotesque transformations on his journey. Leaving their home in pursuit of a magical amulet, Macunaíma and his brothers criss-cross Brazil on their adventure, encountering on the way a multitude of magical creatures and people, including talking animals, the Sun and her three daughters, people who turn into stars and a cannibalistic giant named Piaimã who is also an Italo-Peruvian captain of industry named Venceslau Pietro Pietra. The brothers make it to modern day (1920s) São Paulo on their quest, before going back home to the Amazon find their tribe, the Tapanhumas.

Written over the course of a frantic six days in 1926 and edited over the following months, Macunaíma initially had a limited run of 800 copies. It was (and still is) a work of complete difference – flamboyant and confusing in a cultural landscape that was fairly stagnant at the time of writing. But together with Oswald de Andrade (no relation) and a small group of their peers, Mário de Andrade became a symbol of Brazilian modernism. He was a polymath; a novelist, essayist, poet, musician, photographer and more, who extensively studied anthropology and ethnology, folklore and linguistics. And while it might have been written in just six days, Macunaíma is a coming together of all those influences and the years of intensive study, a multifaceted celebration of Brazil and all things Brazilian, which serves as an attempt to define what was previously undefinable: the national character of Brazil.

Happily for us, this edition contains lots of bonus material which really helps the reader unfamiliar with Brazilian culture to understand more about de Andrade’s work. In addition to the main text, it also contains de Andrade’s Prefaces and Explanations, and a comprehensive, interesting Introduction by John Keene, which sets out the context for the novel beautifully. But the real gems are the Afterword and End Notes by translator Katrina Dodson, which give great insight into her research and translation processes and provide accessible notes to help the reader make sense of this unpredictable narrative. De Andrade wanted his work to sound like the spoken language in Brazil, and the novel contains many linguistic styles as a result; for example, his signature phrase is a pun in both Portuguese and the Tupi language. In her Afterword, Dodson talks of the particular challenge this presents to a translator, and how her primary aim was to reproduce de Andrade’s “linguistic exuberance” whilst keeping hold of the musicality, orality and momentum of his writing. Thus we have in this translation something more akin to a story being told around a campfire, something that is playful and multilingual, rather than a staid, word-for-word translation.

Dodson’s Afterword does much to aid our understanding of the text and learn more about where de Andrade took his influences from, showing clearly how he has woven different traditions and folklore together. For example, the notes to chapter 6 show how de Andrade has mixed Pemon origin myths, Afro-Brazilian folktales, Brazilian ballads and historic events. In chapter seven, we have (among many other things) Amazonian folktales, a blending of African, Indigenous and Catholic spiritual practices, Yoruba deities and real-life friends of de Andrade. Once you start digging into the End Notes, it’s clear just what a far-reaching piece of work this is, and just how much de Andrade must have known about all of these different subjects to be able to write such a piece in just six days. And he has always been quite honest about his influences, never trying to hide them or fully pass them off as his own work. He has openly acknowledged that his ideas have been inspired by existing stories, and the huge debt that he owes to the work of German ethnologist Theodor Koch-Grünberg and his expansive five-volume study of the legends of Venezuelan, Guyanese and Northern Brazilian Indians, Vom Roraima Zum Orinoco, published in 1917.

As I said at the beginning, this is a complex, perplexing rhapsody that takes the reader on an incredible journey. It may not be to everyone’s taste but the best way to approach it, I think, is to surrender to it. Enjoy the language and its rhythms. Marvel at the unfamiliar, the ridiculous and the grotesque, and let yourself be carried along by this audacious adventure. It won’t all make sense, and it will leave you wondering at times what on earth is going on – but once you’ve got to the end you have a lot of material to help make sense of things. Then you can go and read it again and uncover even more wonders than the first time round.

By Mário de Andrade

Translated by Katrina Dodson

New Directions Publishing, 224 pages

Jane Wright

Jane Wright is a web editor, writer and photographer. Her short fiction has been published by Litro, Sirens Call Publications, Crooked Cat, Mother's Milk Books and Popshot Magazine. She lives and works in Manchester.