You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

Sometimes I feel I am more than myself. Sometimes I feel I am connected to everyone and everything. Sometimes it feels as if this life is like a movie I’m watching, in real time, from the inside—a movie entitled: “What it was like to be Alethea Black.” And I am watching it through her eyes, but I’m not really Alethea.

In physics, our understanding of the universe hinges on the idea of an observer. We haven’t applied this principle to our practice of medicine. But what if we did?

When we see infectious microbes, or a tumor, we are observing reality. But what is the fabric of reality—the tapestry against which our observations take place—made of? Could it be made of light?

A tapestry made of light is another way of saying a holographic universe. At first glance, “holographic universe” has the whiff of science fiction, but it’s a serious idea—and one that has lately been gathering steam. The holographic principle was first proposed by Nobel laureate Gerard ‘t Hooft in the 1990s. In 2017, a UK, Canadian, and Italian study provided substantial evidence that the world is, indeed, holographic. But what would that mean?

What if, rather than treating the baseline as zero, we were to treat the baseline as the speed of light. Let’s say this is less like a vacuum, and more like a speeding train. Does the speeding train have any constraints—is the accelerating, expanding universe accelerating toward some limit?

“[O]ur observable universe is at the threshold of expanding faster than the speed of light.” ―physicist Lawrence M. Krauss

Could the speed of light be the dome of Genesis that separates the light above light’s speed from the light below it?

Fig.1 The Flammarion engraving (1888) “A medieval missionary tells that he has found the point where heaven and Earth meet…” Image: Wikipedia

Perhaps, in a holographic universe, we need to re-frame the way we think about light’s speed. Beneath the speed of light, light has speed. At the speed of light, light has no speed. Above the speed of light, light has “reverse speed.”

Could we be reading the cosmos all wrong? We treat the planets as if they were balls of matter in a sea of air. But it’s possible the universe—as predicted by physicist David Bohm, and nearly every spiritual leader throughout history—is all one thing, one fabric. Light.

If what we perceive with our senses is emerging from light, we need to re-calibrate our equations.

Paradigm Shift

Our brains create the images we see. What would ice looking at water see? “Water that is more diffuse than self.” Does ice know itself as ice—or does it see itself simply as water? It is possible that ice looks at water and sees (hallucinates) steam.

What would steam looking at water see? “Water that is denser than self.” Does steam know itself as steam—or does it see itself simply as water? It is possible that steam looks at water and sees (hallucinates) ice.

This same principle could be applied to the perception of light. Perhaps only light can see light as light. Matter looks at light and sees (hallucinates) energy. Energy looks at light and sees (hallucinates) matter.

But neither is seeing reality. It is as if light is a 2D plane that bisects a cone; neither end of the cone can see beyond it. The point looks at the plane from below and calls it sun. The mouth looks at the plane from above and calls it moon.

The observer effect—the way that which is observed can be altered by who is doing the observing—is famously evinced in the double-slit experiment. But I am interested in a very narrow application of it. The powers of hydrogen, or pH, is a hugely important variable in human health.

Are we able to perceive the powers of hydrogen accurately? Perhaps a slightly acidic observer will read water (pH7) as more alkaline than it truly is. And a slightly alkaline observer will read water as falsely acidic. Could misunderstanding pH play a role in disease?

Time’s Pendulum

The point I am making draws upon an idea that has been discussed by Plato and Descartes in the ancient age, and Nick Bostrom and Donald Hoffman in the modern one. It is the world as image.

What if, with cancer, my light is split. It’s like a pendulum that is no longer in the upright position. To one side of time, it thinks light has speed it does not truly have. To the other side, it thinks light has density. Perhaps the cancerous cell is both denser—and faster—than it needs to be.

In other words, does light have speed? Or does light have density? It depends whom you ask. To an observer who is denser than light, it will appear to have speed. To an observer who is more diffuse than light, it will appear to have density. And to an observer with the same frame of reference, it has neither. Ice thinks water has speed. Vapor thinks water has density. Water knows water has neither.

Instead of being “flat,” the basal cell carcinoma on my shoulder now exists on both sides of the speed of light lens. To one side, it’s so cold, it’s burning up. To the other side, it’s so hot, it’s freezing—precipitating out of solution. In lieu of “earth,” it has become … sun and moon. Jupiter and Venus. Saturn and Mercury.

In 2021, I published a paper that applies the idea of a light-based (holographic) universe to human health in the peer-review journal Science & Philosophy. This year, a second peer-review paper was published, “Am I Too Pixelated?” A third peer-review piece, “What We Call the Moon,” is forthcoming, and an article was picked up by InformationWeek.

Before these ideas were accepted by two peer-review journals, they were rejected by every newspaper and every physicist in town. I was roundly ignored and occasionally mocked. I took this as a good sign. I knew I wasn’t just taking a 4000-ton tanker and trying to make it go in the opposite direction. I was taking a 4000-ton tanker and trying to teach it to fly.

My father, Fischer Black, co-authored an equation for pricing options that helped to birth modern finance. After I found a couple of articles that linked my father’s work to Erwin Schrödinger’s, my intuition was that the old dead-cat conundrum had something to do with the perception of time. Is our perception of time accurate?

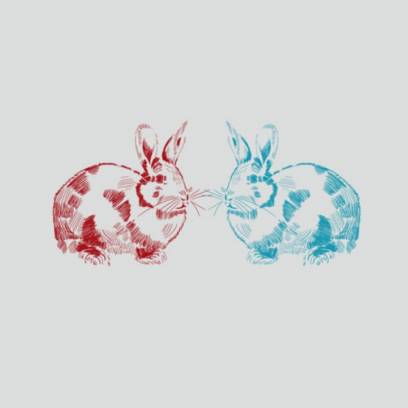

My friend Cynthia is having a Bat Mitzvah for her daughter in Arizona on Saturday. It’s Thursday, and I still don’t know which dress I’ll wear (red or blue), which route I’ll drive (direct or scenic) and where I’ll stay (her house or La Quinta). When observed from the past, time is myriad. Both outcomes exist: the red and the blue.

Fig.2 Achiral images are superimposable; chiral images (above) are oriented left and right

But, come Saturday, time will not be myriad. On Saturday, what was many outcomes will have collapsed to one.

What about the future? How does Saturday look from Monday’s perspective?

Here’s where things get interesting.

Starting Saturday, and ever after, unless I have far too many mimosas with breakfast, I will have worn only one dress.

… in this one universe. But might time encompass more than one universe? Many physicists, including Sean Carroll, support the Many Worlds Interpretation (MWI) of quantum mechanics, first proposed by Hugh Everett in 1957.

Perhaps some of the quantum world’s weirdness stems from the observer’s relationship with time. Unless we are observing the present from the present, there seems to be a lack of parity. It’s as if the past narrows and the future widens. But is this effect an illusion?

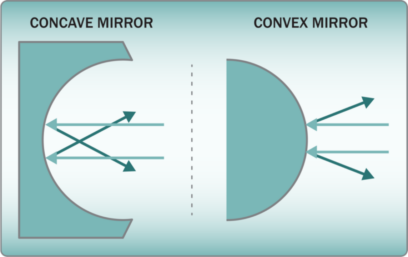

What if, when observed at anything other than its own speed, light appears distorted? When observing the 2D plane from beneath (concave mirror), we see red and blue, superimposed. When observing the 2D plane from above (convex mirror), we see red and blue, splitting.

Fig.3 Concave and Convex Mirrors (Image: John Lunt)

But the truth is neither. The truth is red or blue. “Red and blue, splitting” and “red and blue, superimposed” are reciprocal illusions—noise.

There was never a purple dress. And there never will be (for this one universe) both a red dress and a blue dress.

Schrödinger’s Dress: Below Alpha (“past”), both outcomes exist. It is the red dress and the blue dress, in a state of quantum superposition. Between Alpha and Omega (“present”), there is one outcome per observer, and the two outcomes are parallel. Above Omega (“future”), both the red and the blue outcomes exist, as separate—divergent—arrows of time.

Our perception is perfectly inverted. Observing the present from the past, we see red and blue, but the truth will be red or blue. Observing the present from the future, we see red or blue, but the truth was red and blue.

The Perception of Light

This essay is called “Seeing at the Speed of Light.” Do we see as light sees? Perhaps the crystal at the center of the brain, the pineal gland, is not fundamentally crystal. Perhaps—unless it is under too much or too little pressure—it is light. The pH of my pineal gland will affect how I perceive the pH of my body.

pH7 is essential for life. pH7 is like a 75-degree room. But is my pH7 a passive pH7, or is it one I am creating with a lot of work? Is my body a true 75-degree room, or is it a room made of ice, with the heat on full blast? Or a room made of steam, with the A/C on full blast?

Once I alter my core metabolic rate, I can turn on the heat or the air conditioning (so to speak), by altering my pH. But is a brain that is slightly too hot or slightly too cold—slightly too acidic or slightly too alkaline—able to read the world objectively? I have seen a patent application for LSD “acid” to treat Alzheimer’s.

Dubbed “the seat of the soul” by René Descartes, the pineal gland contributes to our understanding of circadian rhythm and is the font of the neuroendocrine cascade. If time is critical to human health, the pineal gland is critical. But what if my pineal gland itself is “too dense” or “too diffuse”?

Recently there has been exciting research into the evolution of life as a function of proton gradients. A proton gradient is a measure of density. Let’s say there are three varieties of apple: dense apple, regular apple, and diffuse apple. Dense apple wants to expand; diffuse apple wants to condense. However, if my individual understanding of density is skewed, for me, it might be “double-dense” apple, dense apple, and regular apple. But there’s a problem in this scenario. “Double dense” apple is not one apple. It’s two.

If I make myself too dense—if my pineal gland is too dense, therefore my image is too dense—the baseline state is no longer homeostatic (stable). If my density is double the baseline, for me, the world is exploding (Parkinson’s?). If my density is half the baseline, for me, the world is condensing (ALS?).

To an observer who is “double dense,” the baseline state is exploding by a factor of two. To an observer who is “triple dense,” the baseline state is exploding by a factor of three. Do proton gradients—excess density—play a role in embryogenesis, where we sometimes produce twins (triplets, quadruplets, etc.)? Do proton gradients play a role in cancer?

Fig.4 Joshua Tree Star Trails (Photograph: Mike Ver Sprill/Shutterstock)

In conclusion, this essay asks a simple question. What if we are not in a vacuum—we are inside time. And time has a “proper” (consensus) speed. When time is too slow, light has to be too fast (Chronic Fatigue Syndrome?). When time is too fast, light has to be too slow (Autism?).

The functioning of my pineal gland is extremely important, but limited. My pineal gland cannot read the speed of light in an absolute sense; it can only read the speed of light vis-à-vis itself. If it is too dense, it will read light’s speed as too fast.

But light’s speed cannot be too fast. When light’s speed is too fast, it begins to precipitate out of solution—to “spin backward,” like a hot room with the A/C on full blast. When light’s speed is too slow, it begins to burn up—to “spin forward,” like a freezing room with the heat on full blast. In other words, we see backward. It’s an upside-down world. What are we really seeing when we look at the so-called sun? We don’t see light that goes to the moon. We see light that goes to the moon and back.

When my friend with ME/CFS (Chronic Fatigue Syndrome) told me that taking GABA, a calming neurotransmitter, paradoxically made her feel panicky and hyperactive, I was not surprised. Depending on the conditions of the terrain, my brain seems to be able to utilize the same substance (neurotransmitter, vitamin, mineral) to do either a thing, or its opposite. By “my brain,” I do not mean my physical brain. I mean my genes. My code.

Hope for the Future

We’ve all been through a great tragedy—a series of tragedies—and we’re in shock. And worse: we are polarized. Because the survival part of our brains, the amygdala, has been so relentlessly stimulated, we have perhaps failed to notice that beneath the tragedy, something is happening here.

After a lot of time indoors, the other day, I went to an old favorite spot—the organic coffee shop on Main Street. There, where the road flattens out and you can see for a long distance in both directions, I stood for a long while and listened. The air seemed somehow magical—the light so thick and golden, almost like something you could reach out and touch. After a while, I finally realized: it wasn’t spinning.

I didn’t understand, at first, the mighty power of consciousness. Of fiercely believing, in my body and my soul, that everything would be all right in the end. Of ceaselessly praying, with my heart and my mind, for the well-being of every person on Earth. Of fearlessly holding love within me like a flame.

But now I do.

Am I my DNA? No. My consciousness is executing this DNA. But this DNA can be executed by any consciousness, and all consciousness, at base, is one. There is, ultimately, only one observer here, Lord. You.

A final word for the little girls who will grow up to be the physicians and physicists of tomorrow: When this essay was rejected a million times, when I was ignored and mocked, when friends and family looked at me as if I were crazy, and I felt cosmically alone, did I give up? I never did, and I never will, for no matter how many millennia some spark of life plays the role of Alethea. Don’t be fooled by social media. Life is not a popularity contest.

It is a chance to love, and to laugh so hard you cry, and to cry so hard you laugh, and to lift up the lowly, and bind together what is broken, and give yourself to the world. It is a golden day—one simultaneous day, although it feels like many—in which you may take your light and use it to blaze across the sky like a thousand roman candles. It is an invitation to not be swayed by public opinion nor cowed by power but to stand up, ask questions, and think for yourself. To remain, in spite of everything that will happen to you, your glorious, simple, self.

Alethea Black

Alethea Black was born in Boston and graduated from Harvard in 1991. Her memoir (You’ve Been So Lucky Already, Little A, 2018) was reviewed by The New York Times. Her father, Fischer Black, co-authored the Nobel prize-winning Black-Scholes equation.

- Web |

- More Posts(1)