You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

1967–1991

You’ve been talking again.

What about?

The past.

It’s all I’ve got. Anyway. Aren’t the dying allowed to rant?

*

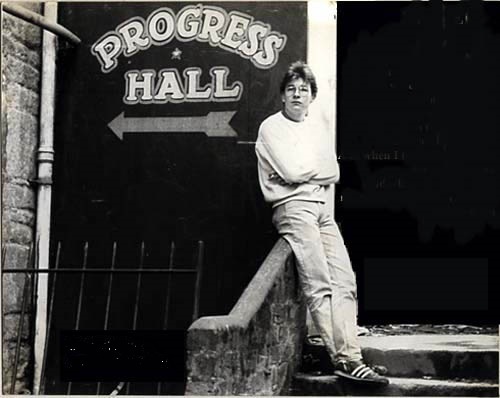

Thursday nights, we played table tennis in the Progress Hall. Jimmy swinging his arm in a loose arc to smash the ball. Bright smile and new trainers. The one place he didn’t have to look over his shoulder.

Boys in school were uncomfortable around Jimmy. His voice. His long-fingered, soft-skinned hands. Not the kind of hands that could swing a hammer or smash a face.

Jimmy’s mum said he had musician hands. She’d been making Jimmy take violin lessons for as long as anyone could remember. Jimmy’s dad was years gone, with only rumour left in his wake.

I was the only friend Jimmy had at school. I protected him but Jimmy had to stay close. Safe in my shadow. And that was okay. No one bothered me because of my size and the way I looked. Even adults were a little afraid of me.

But I had my own problems at home. I’d disappear for days and Jimmy had to survive on his own. Jimmy liked to call me Garbo because of it.

I always came back though, sometimes turning up in Progress Hall. Jimmy would come over straight away. “Welcome back, Garbo,” he liked to joke. “Good you got tired of being alone.”

Father Kerry ran the table tennis club. He was in his seventies but he still liked to play a few points now and then. Mostly he preferred to sit by the kitchenette doorway, drink tea, smoke cigarettes. He always looked pleased, like we were something he was proud of.

*

I was on the internet yesterday.

Internet? Stay out of those chat rooms.

You can trace all sorts of people. Your friend plays violin for a well-known orchestra.

See those doctors and nurses over there? They don’t know what to do. I can see it in their faces. You can’t stop this disease once it’s in you.

Don’t think like that. Don’t. Tell me some more about Progress Hall. Tell me about Jimmy.

*

One time I found Jimmy on the floor of the school toilets. They’d beaten him pretty bad. He wouldn’t say who did it.

I helped him to his feet. He looked me right in the eyes. “Why always me?” he asked.

“Jimmy,” I told him. “You know why it is.”

Jimmy pushed past me. He ran into the corridor and headed for the fire exit. I followed him. He opened the fire-exit door. He stepped out onto the open street and turned around. Standing there in the sunlight, looking back at me in the darkness.

“You think you all know me,” he said. “But you don’t!”

That week Father Kerry fell ill and before people even got used to the idea, Father Kerry was gone. A young priest was sent in to run the parish. Father Paul. He had crow eyes and polished shoes and sour breath.

On the very first day he took our class for Religious Instructions, he asked Jimmy to join the church choir but Jimmy said he was too busy.

Father Paul said, “How can you be too busy for God?”

Jimmy looked back at him with contempt.

“It isn’t God asking.”

You knew it right away. They were enemies.

Jimmy refused to attend Religious Instruction Class after that. The headmaster talked it over with Jimmy’s mum and they agreed that Jimmy could study in the headmaster’s office during the religious instruction period. Father Paul was furious but the headmaster wouldn’t budge.

But Jimmy had a victim’s bad luck. The headmaster was hurt in a car accident and had to retire. The new headmaster had no time for Jimmy or Jimmy’s mum. So Jimmy had to come back to Religious Instructions Class. Father Paul made him sit at a desk right at the front. Father Paul circled around Jimmy’s desk like a black shadow. Sweating when his orbit tightened around Jimmy. Thinking none of us could see his excitement. I never understood back then how a man like that would want to be a priest.

*

It took Father Paul about two months to find out we were still using Progress Hall for our table tennis club. One of the old parish nuns had Father Kerry’s spare key. She opened the hall for us every Thursday. She never stayed, because she had to get along for evening prayers. So one of us would take the spare key back to the convent and slip it inside her letter box.

Father Paul walked in and everyone stopped what they were doing.

“Who gave you permission for this?” he asked.

“Father Kerry,” Jimmy answered.

Father Paul ignored Jimmy. He looked at the rest of us. “Who gave you permission?”

Jimmy stood his ground. “It’s our table-tennis club. Father Kerry started it.”

Father Paul looked around. “There’s that voice again. That girl’s voice.”

The other kids were too afraid to look each other in the eye. Ashamed for Jimmy. They folded up their tables and pushed them into the storage room and took their coats and left.

Jimmy watched his world end and couldn’t accept it.

Father Paul finally looked at Jimmy with that tight smile of his.

“You put that table away and get out of here.”

Jimmy threw the bat at Father Paul.

Father Paul jumped to the side and it embarrassed him. Jimmy laughed. Father Paul jabbed a finger at Jimmy. “You watch out.”

Jimmy took a long breath. “You can’t have me.”

Father Paul cried out. Charged Jimmy.

Jimmy hadn’t expected that. Laughed.

Father Paul was bigger and stronger. He smashed into Jimmy and the table moved with them. Father Paul gripped Jimmy in a headlock and forced him down until Jimmy’s head was on the table. He moved behind Jimmy, spreading his hand on the back of Jimmy’s neck, pushing down with the flat of his hand, using his body to pin Jimmy down.

Jimmy turned his head and I could see the fear.

I stepped forward and I punched Father Paul on the side of his head. He slumped to the floor. He tried to get back up, but his legs had given out. He looked up at me and I hit him again.

He rolled onto his side and pulled his legs up. He turned his head away. I think he thought I was going to kill him.

I kicked him in the ribs and then I leaned over to hit him again when Jimmy pulled me away.

We ran down to the harbour. Jimmy was excited. He talked about the two of us getting some money together, packing some rucksacks and making a run for it. Leaving the town and everyone else behind. He was still talking like that when the police car pulled up and Sergeant Heaney stepped out. He shook his head as if he was sorry for us and told us to get in the car.

We were expelled from school. Father Paul insisted on pressing charges. Jimmy’s mum had money for a decent solicitor. He did some community service. But I was branded “a feral loner with a taste for violence”. and sentenced to six months in a young-offenders institution.

When I got out Jimmy and his mum were long gone. I made some bad decisions after that. So many mistakes. So many wrong turns. I used to think it was Jimmy who had all the bad luck but really, it was me. I was the one destined to fail at everything. And now I’m dying. I don’t have any more stories for you. Leave me alone.

*

“Hi. It’s me again. I have someone with me. Your friend’s here. Jimmy’s here.”

“Hey, Garbo. I tried to find you. Went off on one of your walkabouts did you? Hey. I’m married. I have a family. Let me show you some pictures. See?”

“That’s nice, Jimmy. Listen, I wish I’d just said it back then. How you had such beautiful hands. It’s alright, Jimmy. You don’t have to say anything back. Everyone thought they knew me too. But they didn’t, did they? Let’s pretend we’re in Progress Hall. It won’t take long.”

Mark Gallacher

Mark Gallacher is a Scottish writer who lives in Denmark with his wife and two sons. His stories have been shortlisted for the Fish Short Story Prize, longlisted for the Retreat West Short Story Competition, and published in New Writing Scotland in print and online literary magazines and anthologies in the UK, Denmark and the USA, most recently in Causeway, Dark Lane Anthology Vol. 7, Flash: The International Short-Short Story Magazine, and DreamForge. He has published poetry in print and online, in Acumen, Monday Night, Magma, Orbis, 3:A.M. Magazine and many more.