You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

From its opening sentences, Sang Young Park’s bestselling novel Love in the Big City had me engrossed. As the narrator attends the wedding of his university best friend and former partner-in-crime Jaehee, he is casually informed of a rumour that he has died and notices how all the thirtysomething guests are “aging at different speeds.” These passages evoke a very peculiar kind of loneliness; it’s the wistfulness people in their thirties feel when they encounter anyone they knew in their teenage years and early twenties, no matter how self-destructive these years may have been. It’s a feeling I know well. This is where Love in the Big City excels: in the witty and measured depiction of emotions most of us know well.

Told in four parts and translated into English by Anton Hur, the novel explores the formative life of a young gay man in Korea who is only ever referred to as “Mr. Young” or “Mr. Park.” Each section focuses on a major relationship in the character’s life: from Jaehee to a string of romantic dalliances. What unites each of Park’s characters is a sense of alienation as they never quite manage to form meaningful connections. “I […] got drunk and slept with a new man every night. And every morning, I realized anew that the world was filled with lonely people,” the narrator says of his university days.

From its first part, which is named after Jaehee, the novel’s pervading themes are clear in the youthful vigour of the two best friends: “The world was just not ready for the boundless energy of poor, promiscuous twenty-year-olds. We met whatever men we wanted without putting much effort into it, drank ourselves torpid, and in the morning met in each other’s rooms to apply cosmetic masks to our swollen faces and exchange titbits about the men we had been with the night before.”

There is something equally intoxicating and unsettling about the characters’ rebelliousness as Jaehee “could toss societal norms aside like a used Kleenex.” When the pair eventually move in together, it leads to a rumour that they are a couple and she often acts as a shield for the narrator’s sexuality, posing as his girlfriend as he is called for military service. When Jaehee meets and finally marries an engineer, Park poses a question that is at the centre of the novel: what happens to those of us who are left behind when our friends move on?

In the case of Park’s narrator, he finds solace in a number of relationships, with varying success. The first is with an impossibly handsome older man he meets in an adult education class, which is ironically titled “the philosophy of emotions.” Immediately, the relationship is unhealthy and obsessive. “Concentrating on the heat of his skin and the sound of his breathing whispering in my ear made me completely lose sense of who I was. I became something not me, not anything, just another part of the world that was him,” the narrator comments.

After this relationship ends, he meets Gyu-ho and begins what we assume will be one of the most significant relationships of his life. In these scenes, Park is unflinchingly honest about every aspect of romantic love, including the realities of erectile dysfunction, with the narrator complaining that Viagra causes the pair to suffer from indigestion and blocked noses.

Despite this, even the most cynical reader will be affected by scenes in which the two walk in the rain. “When I saw his face – Gyu-ho, who always seemed more at peace than anyone else I knew – my heart melted a little.” As is characteristic of his style, the writer manages to take a scene that has the potential to be riddled with cliché and create a genuinely touching moment between two damaged characters.

Through this relationship, Park also points toward one of my favourite themes of the book. Although the narrator perpetually views himself an outsider, Gyu-ho makes numerous attempts to form a deeper connection, but the protagonist is too broken to respond. Although not always likeable, the characters are undoubtedly relatable.

While Park justifiably has a reputation as a rising star of queer fiction, he never takes a didactic tone when it comes to the theme of sexuality, despite the heart-breaking challenges the narrators faces as a gay man. Rather than preaching to his reader, he skillfully makes his point though the events of the plot. When the narrator visits a sexual health clinic, he overhears two workers describe him and his boyfriend as “faggots.” “I finally realized this was something I should’ve been angry about from the beginning, and that I had a tendency to laugh loudly in situations where I should be angry.”

Without revealing too much of the plot, the most horrific response to his sexuality comes from his mother who walks in on him kissing another boy at the age of 16. Coming midway through the novel, this revelation helps justify – or at least explain – some of the seemingly self-indulgent behaviour we’ve previously observed in the narrator.

While Love in the Big City is unfailingly honest in its depiction of family dysfunction, abortion and cancer, there is also a lyricism to many of its passages, which is a real testament to the skill of its translator, Anton Hur. There is, for example, a poetic quality to descriptions such as: “My sentences formed like lines coming out of my fingertips. They kept on coming without my thinking about them, as if they had a mind of their own.” The narrator’s loneliness following a breakup permeates simple, bleak sentences such as “it enraged me to hear people talking about love. Especially when it had to do with love between gay people.”

Likewise, the novel is often genuinely hilarious with absurd moments punctuating even the most painful episodes in the narrator’s life. It’s difficult not to laugh when, during one of the most emotionally excruciating points in his relationship with his older boyfriend, a stranger dressed as a zombie for Halloween asks for a photograph, or when Jaehee steals a model uterus from an abortion clinic.

Another of the book’s strengths is its ability to ground both its characters and reader in a moment and a place in time. “The moon and streetlamps and neon signs of the whole world seemed to be shining their lights just for me, and I could still hear the strains of a Kylie Minogue remix in my ear.” At this point, the sense of place is dizzying, although it was as easy for me to remember my own youth in noughties London as to imagine myself in Korea during a similar era.

Was there anything I disliked about the Love in the Big City? While not a criticism, the book’s four-part structure is often non-chronological, which does mean the reader needs to stay alert to which events occur in which time period. Ironically, another characteristic I initially found a little jarring – the narrator’s tendency towards introspection – became one of my favourite aspects of the book as I read on.

Readers of the early sections may be tempted to dismiss the protagonist as a Millennial snowflake as he makes statements such as “I was too busy getting trampled on by life to remember a lot of the little things of daily existence.” However, Park meticulously develops the arc of his protagonist, drip feeding key, and often brutal, biographical details. As we slowly learn more about our main character, we grow to understand, and empathise with, some of his less-than-heroic traits. And, although the novel is never overt or heavy handed in its social commentary, it does deliver one of the most painfully astute observations I’ve read in a long time, as the narrator and Jaehee discuss sexual freedoms. “[She] learned that living as a gay was sometimes truly shitty, and I learned that living as a woman wasn’t much better.”

Read my Interview with Anton Hur here.

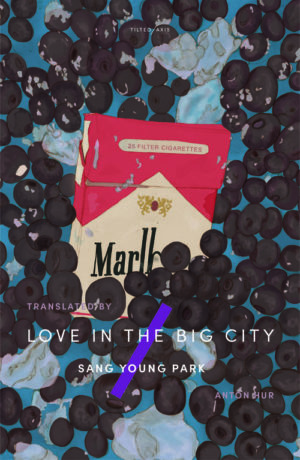

Love in The Big City

by Sang Young Park

Tilted Axis Press, 240 pages

Katy Ward

Katy Ward is a freelance journalist from Hull. Her work has appeared in The Metro, The Overtake, LoveMONEY and Independent Voices. She has a BA in English from Oxford University and a postgraduate diploma from City University.