You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

The French original of Blue, entitled Le testament des solitudes, won the Grand Prix littéraire de l’Association française in 2009. Its author, Haitian journalist, poet and novelist Emmelie Prophète, was born in Port-au-Prince in 1971. Her other novels include Le reste du temps (2010) which tells the story of her relationship with murdered journalist Jean Dominique. Prophète has worked as a broadcast journalist, a cultural attaché and as the director of Haiti’s national library. As a writer, however, she occupies spaces that are abandoned, misrepresented and unseen, spaces that are inaccessible to the international literary elite, to her readers in Europe, to the government, the police, to anyone on the outside looking in.

Emmélie Prophète writes Port-au-Prince through the daily lives of its least visible inhabitants, simultaneously inviting and resisting voyeurism. In an interview with Thomas C. Spear for île-en-île, Prophète remarked, “I am fundamentally a city-dweller and port-au-princienne […] The city is my place, it is the city that inspired me. I really like being in the city, in this city of blackouts, this city that is always too dirty, this city of misery, but which I accept and love, despite everything.”

In Blue we don’t get so much of the dirt of the city, the tangled, jarring rhythms of the streets. Instead, Prophète places her narrator in the lounge of an airport. Travelling alone from Miami to Port-au-Prince, the narrator finds comfort in this liminal space. She feels free to ponder the silence that surrounds her homeland, her mother, her aunts, and her own inner thoughts. Between two places, she sees how living in poverty keeps women silent, forging their identities around practicalities and resilience. The airport lounge thus becomes a vulnerable and intimate space in which we lose sight of the representations that so often attach to Haitians in North Atlantic media. Equally importantly, we lose sight of the conventions that force the arc of a story onto a piece of narrative prose. Instead, images of a ravishing Caribbean island seep through the texture of the cloth that Prophète works with. The result is captivating. Equally, the voices she conjures emerge like a radio frequency tuning in and out, balancing pain and anger with the comfort women provide for each other.

It is an interior piece, but the outside world does intrude on this meditation on family and memory. Our narrator’s world is now ravaged by a void that has gripped all media outlets, all words and stories: 9/11. She is caught in the act of folding inwards, in order to collect within herself the last bits of hope that have scattered like rags in the wind in order to smooth them out on a table. This table is not set for a homecoming feast, but as a stage for her characters to act out the narrator’s childhood. The love with which Prophète stitches these rags together is conveyed by a style that embraces the moment. These moments are poems in which “blue” is a synonym for “home”, where “any voyage is possible”, and where she is walking a long, pebbled dirt path to school again. Profound psychological truths trip lightly off Prophète’s tongue. Her mother is burdened with household duties, as are the other women of her neighbourhood. The narrator as child looks on as they become hardened to their fate and fearsome to their children, or so soft that they are ineffectual and can offer no maternal presence.

This testament of solitudes explores the fate of family members who can only be considered as insignificant in the frame of geopolitics. However, the narrator, who never ceases to travel, to leave, and to come back again to her childhood home, manages to charge these characters with the universality of their lives. Snatches of reminiscence are recomposed, step by step, in which three sisters and their mother note their triumphs and regressions.

Prophète pulls off a tricky proposition. She listens to all the voices that reside in her mind, separating them out as mother, sister, aunt or remnant of her own younger self. None of these voices are her property, she does not lay claim to authorial omniscience. Instead, she searches for what has gone unnoticed: the substance of a woman’s life when it is lived in poverty. This heritage is none other than Haitian, but it is true to any life lived in hardship.

Her geographical distance works to make the writer in her feel as close as possible to this island in the Caribbean Sea, and these three sisters and their mother, “born between dead fields and sad rivers, the only dream they had inherited was that of leaving.” Women who experience different destinies and the tension that comes with growing apart. But what brings them together is their absence from public life, as if at the same time as they are trying to acquire the signs of affluence, the world is pushing them aside and they themselves are disinvesting from it; “mastering” neither the language, nor its meanings, still less its codes. It would be fair to say that Prophète’s characters are not fleshed out as recognisable protagonists. They remain stubbornly vague and shadowy, and it is sometimes hard to keep track of their individual stories. But this reluctance to emerge into the full light of the reader’s attention is appropriate for Prophète’s vision.

It is our narrator who finds places in the world in which she can be wholly true to herself. Prophète is fantastically funny about the processes and cliches of travel. She is uncompromisingly herself. In these moments, in this airport lounge, she holds the family together, while drinking a Starbucks cappuccino – “[It] doesn’t even have a scent anymore.” Whilst she drinks it, she remembers a ritual from her childhood:

“Each girl born into this family takes over this ritual, which stops only with death.”

The instruments of this daily rite consist of a pan of beans roasting on the fire. Then the process begins of grounding these beans:

“A young girl on either side of the mortar, each with a long and heavy stick, pounding the coffee forcefully by turns. Their clothes are completely black from the dark coffee powder afterward. The brew that is prepared from this and served to everyone is strong, full-bodied. I never pounded the coffee beans myself, but God, how I loved to watch.”

It is worth noting the three young girls in this scene. The two girls who are actively working the pestle and mortar become shaped by the process – their appearance, their musculature no doubt, their identities are formed by it. So, too, does the third girl find her shape, her role, her purpose. Hers is to watch, to love, to remember and to write.

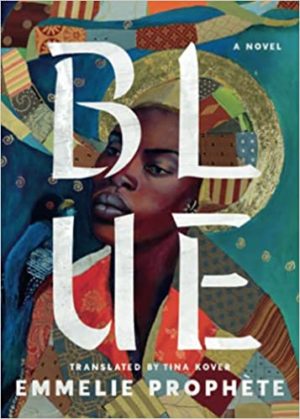

Blue: A Novel

By Emmelie Prophète

Translated from the French by Tina Kover

Amazon Crossing, 128 pages

LILIAN PIZZICHINI

With a background in teaching and journalism, Lilian Pizzichini is the author of Dead Men’s Wages (winner of 2002 Crime Writers’ Association Gold Dagger for Non-Fiction) published by Picador. In 2009 Bloomsbury published The Blue Hour: A Portrait of Jean Rhys (BBC Radio Four Book of the Week) and in 2014, Music Night at the Apollo: A Memoir of Drifting, a Spectator Book of the Year. Her fourth book, The Novotny Papers, was published by Amberley in May 2021, and featured in The Daily Telegraph and Daily Mirror's "Big Read".